What’s so special about Special Collections? Inside the College Archives and Chapin Library

February 8, 2023

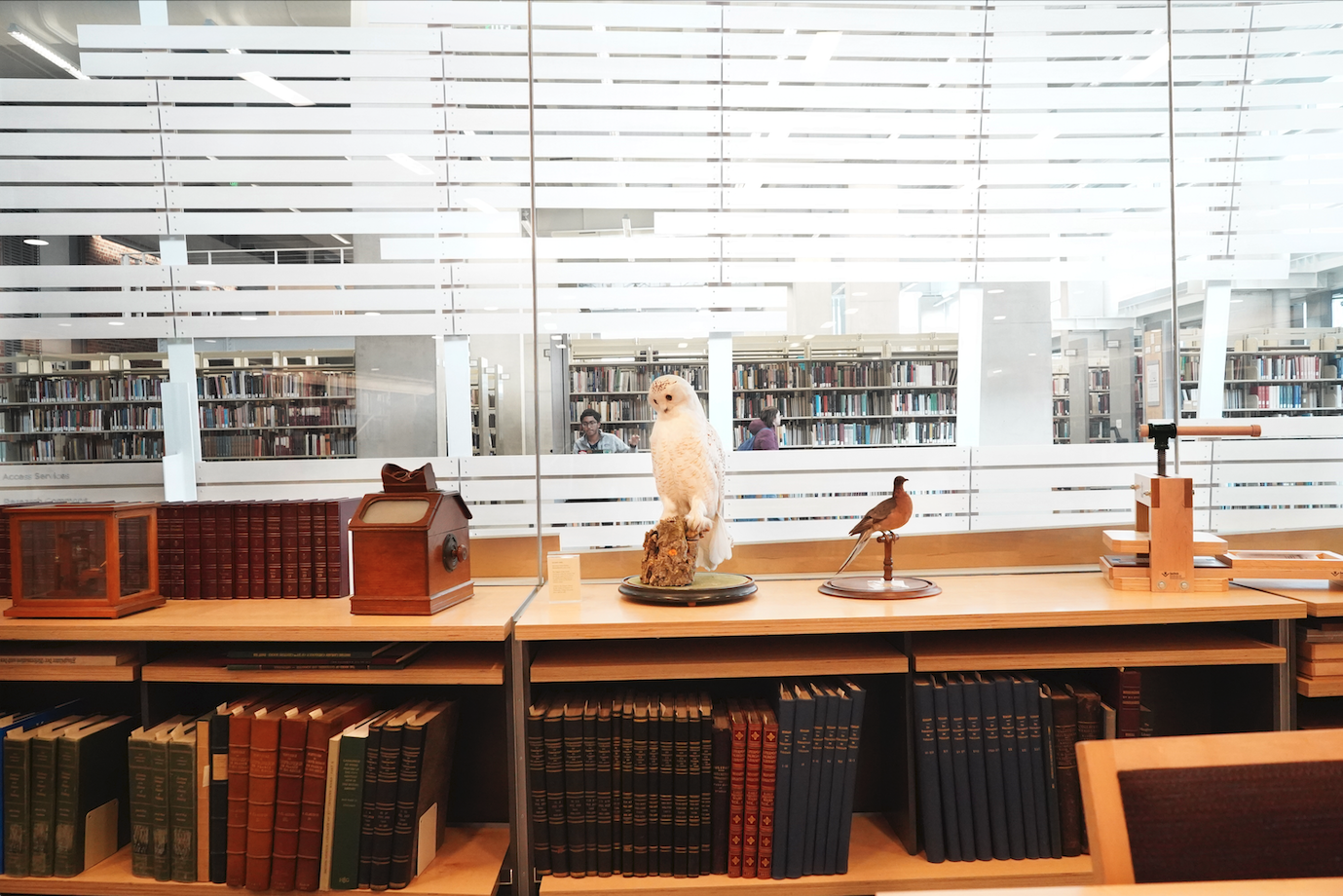

The third floor of the Sawyer Library is a popular study spot for students at the College to work on papers and problem sets. Just above it, however, is a very different space — Special Collections — which holds hundreds of thousands of items that are catalogued separately from those in other parts of the library system.

Until 2014, Special Collections existed as a separate department from the College’s library system. Today, it is composed of two main components: the College Archives, which contain materials pertaining to the College’s history, and Chapin Library, which holds rare books and other special materials outside the scope of the Sawyer and Schow library collections. Together, the College Archives and Special Collections receive about 100 class visits each year according to Head of Special Collections Lisa Conathan.

The College Archives work to preserve documents related to the history of the College and its faculty, staff, and students. The department collects and organizes College records that have particular legal and fiscal importance and oversees a variety of the College’s holdings, including the Shaker Collection, the Sawyer Library rare book collection, and The Sterling A. Brown papers.

The archives focus on the literature surrounding the history of the College, including notable regional and national events pertaining to its legacy. They also collect primary documents dealing with College events as a means of recording the development and legacy of the College, with special attention to its educational philosophy, how it interacts with the greater Berkshire community, and the activities of its student body and faculty. Some of these documents date back to the 18th century, including documents describing the transfer of land from Mohican individuals to English colonists, Conathan said to the Record in an interview.

The archives also hold various research and outreach initiatives to present these documents to the College community and the greater public, such as the Oral History Program, an initiative that interviews members of the College community about their experiences at the College.

One such example is the set of interviews conducted for an archival exhibit, held on April 6, 2019, coinciding with the College’s “50 Years of Africana Studies” celebration, where alums were interviewed about their experiences with the department. Conathan discussed how these oral recordings added another layer to the College’s ongoing records. “You can imagine that, in the written record, certain stories get told,” she said. “Talking to people can help fill out and make [those stories] a little bit more rich.”

When asked to highlight a current exhibit at the College Archives, Conathan mentioned one created by students in a course titled “Architecture of Williams College,” which was taught by Professor of Art History Michael J. Lewis this past Winter Study. Students were asked to examine architectural documents reflecting the history of the College campus and then plan an exhibit for the College Archives with these blueprints as the focal point.

Conathan pointed out how this exhibit spoke to the multifaceted nature of the documents contained within the College Archives. “These blueprints [were] created because of a building project or a renovation project, and now they’re being used to research the history of modern architecture in this region,” she said. “We’re always looking for things that have multiple purposes.”

Special Collections’ other component, Chapin Library, holds 60,000 volumes, which were organized into eight categories at the time of the library’s founding: 15th-century printed books, American history, English literature, European literature, classical literature, American literature, bibles and liturgical works, and books on the history of science. Since then, though, the collection has expanded in scope and organization.

The Chapin Library was established in 1923, funded by a gift from Alfred Clark Chapin, Class of 1869. The Chapin’s original gift included 6,000 volumes, including the Eliot Indian Bible from 1661, which was the first bible printed on the North American continent and the first bible to be translated into an Indigenous American language. In addition to its over 60,000 volumes, the collection holds over 100,000 other materials.

According to Chapin Librarian Anne Peale, the library is unique in that its focus has always been squarely on supporting the curriculum at the College. “From the start, the Chapin’s collections were built to support education at Williams, and that’s really unusual for special collections,” she said. “Most university special collections began as natural accumulations of books the university has had over time or as private collections that are directed by the passion of one individual. Alfred Clark Chapin wasn’t collecting for those purposes — he was building a teaching collection.”

Aside from the Eliot Indian Bible, the library’s holdings include one of 21 extant copies of the 1465 edition of Marcus Tullius Cicero’s treatise De Oratore produced in Subiaco, Italy — the first-ever classical work to be reproduced in print and the first work to be printed outside of Germany using the printing technology that originated there.

In its own room, the Chapin Library also has a set of American founding documents, which are on permanent display. The College is the only institution other than the National Archives in Washington, D.C. to possess original copies of the Constitution, the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence, and the Bill of Rights. The Chapin’s Constitution is not a final copy but a printed draft with George Mason’s final edits handwritten in the margins.

Like the Constitution, the Bill of Rights on display at the Chapin is not a copy of the finalized document. Rather, it was one of 100 copies printed for the U.S. House of Representatives. Once the House approved the document, it went to the U.S. Senate, where further changes were made. The first edition of the Articles of Confederation shown in the Chapin Gallery is one of nine surviving copies of the first printed edition.

The Declaration of Independence held in the Chapin Library is one of 26 remaining copies of the Dunlap Broadside — the first printed version of the Declaration. Despite the document’s significance, an unknown person seems to have used the document as scratch paper — a tabulation of colonial currency is visible on the back of the page.

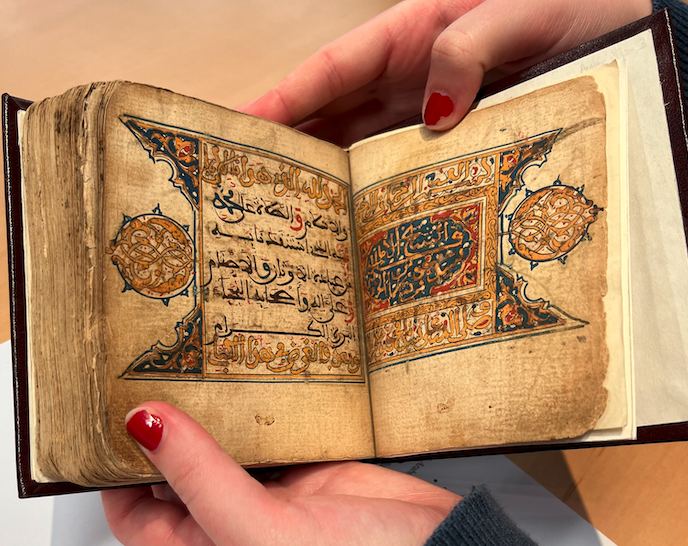

Peale said that the Chapin Library is always looking to expand its collection, incorporating a more diverse set of perspectives. “Special Collections is not just the [De Oratore], although that is an incredible book,” she said. “One of our goals is to diversify the range of voices that we have in the collection and to broaden the scope of material beyond the western European canon.”

Some recent acquisitions towards that goal include an early edition of Our Bodies, Our Selves, which is a 20th-century feminist text; a Japanese atlas of the Americas dating to 1855 — two years after American naval ships entered Tokyo Bay and re-established trade between Japan and the Western world for the first time in 200 years; and a series of community cookbooks shedding light on the experiences of immigrants in the United States.

The most important part of the library’s mission, however, is to keep its collection accessible to undergraduates. “There’s massive scope … and that’s what keeps the job fun and exciting,” Peale said. “We have the resources to make that material accessible to undergraduates in a way that almost no other institution of our size can — we’re really, really privileged.”

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the College Archives alone receives 100 class visits per year, misnamed the Sterling A. Brown papers collection as “The Life and Lore of Sterling A. Brown: Celebrating Poetry, Prose, and Music,” stated that the Oral History Project interviews only past and current students, and characterized “50 Years of Africana Studies” as a past exhibit of the Special Collections. It also incorrectly stated that the Chapin Library currently contains eight categories of items, that there are seven remaining copies of the Subiaco edition of Cicero’s De Oratore, that the De Oratore was the first printed work produced outside of Germany, and stated that the image of a manuscript in the genre of madḥ and salawat in the article was that of a Qur’an.

Special Collections as a whole receives 100 class visits per year and the Oral History Project interviews individuals from across the College community, not just students. “50 Years of Africana Studies” was a College-wide event that included the work of various departments at the College; the Special Collections held a coordinating exhibit. While the Chapin Library’s collection was organized into eight categories at the time of its founding, it has expanded in scope since and now is organized differently. There are at least 21 surviving copies of the De Oratore, and it was the first printed work produced outside Germany using the technology that emerged there. However, it is predated by a number of East Asian works printed by different kinds of presses. We regret these errors.