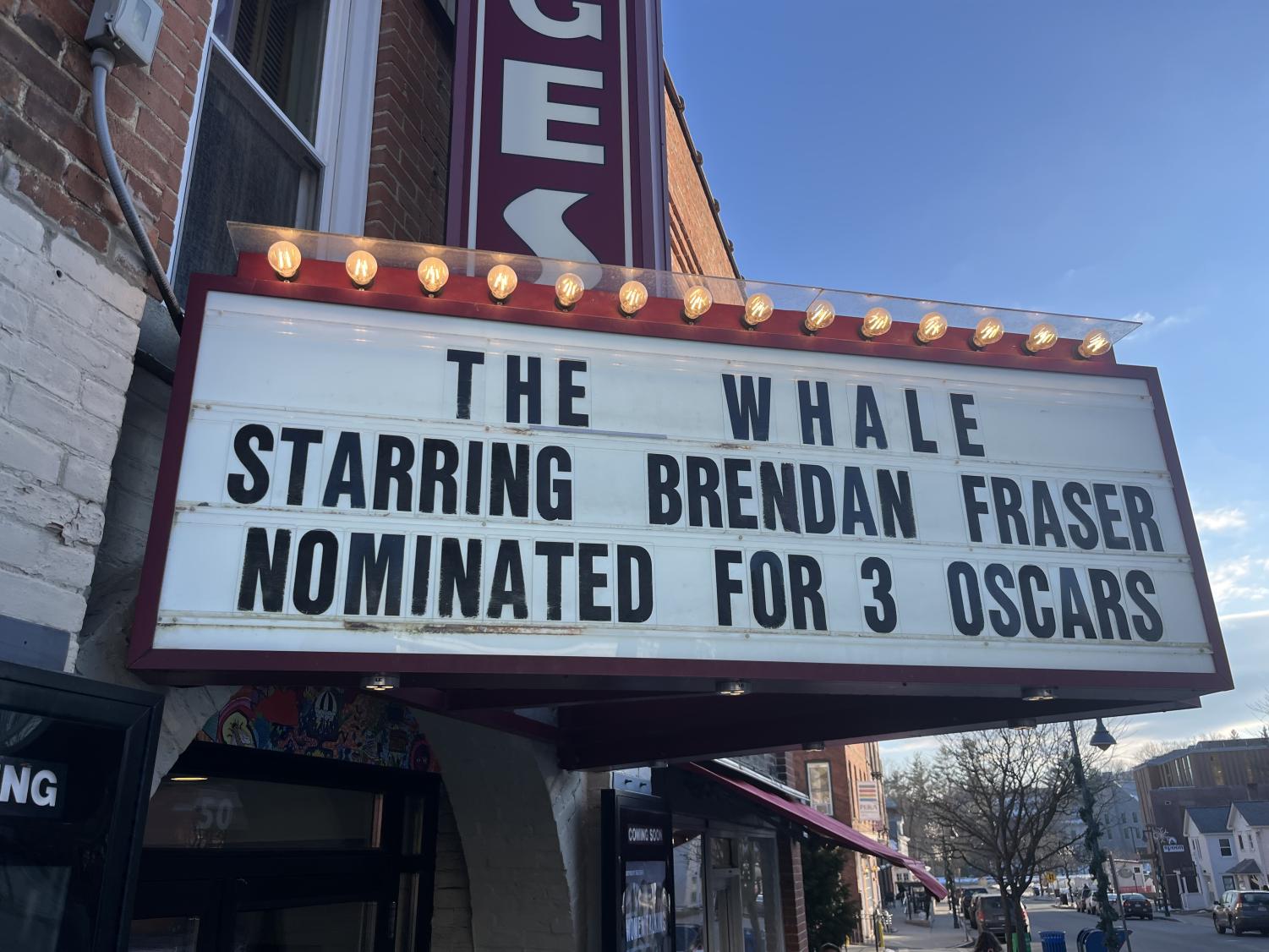

Images in Review: The Whale

February 8, 2023

With Oscar nominations recently released and a cold front slowly subsiding, we are all in need of a new film to keep us captivated and indoors this winter — and The Whale is certainly that film. Directed by Darren Aronofsky and written by Samuel D. Hunter, The Whale tells the story of an English professor named Charlie (Brendan Fraser) who struggles with obesity and imminent congestive heart failure. The film follows him as he teaches virtually, confronts the potential final days of his life, and attempts to reconnect with his estranged daughter Ellie (Sadie Sink) and ex-wife Mary (Samantha Morton) as his health rapidly declines.

While Charlie refuses all healthcare offered to him, we helplessly watch him grieve his past. But he reckons with the loneliness of the end of his life — spent largely alone and immobile — in an unexpected way.

What makes Charlie such a charming character is his unrelenting positivity about the few people in his life, including Ellie, Mary, and his friend and nurse Liz. This kind of hope that Charlie exudes at the brink of his own death feels nothing short of radical. In the face of seemingly endless abandonment, hatred, and judgment, Charlie never stops seeing the best in people. He helps the people around him — his students, his daughter, his friend, the wandering missionary that keeps knocking on his door — to see the good in themselves and speak their minds. Though sometimes naive, Charlie’s confidence in the inherent good of others is undeniably endearing, and the fact that he can see light in the face of adversity is enough to make any viewer reflect on their own cynicism.

Aptly titled after a massive sea creature, the film primarily paints a picture both of captivity and magnitude. The audience wants for Charlie what the people around him want: salvation. Instead, Charlie is held captive in his home, grieving over his former partner Alan and enraptured by the person he believes his now-grown daughter Ellie to be. He is a man of sometimes excruciating compassion with few people around to accept it. His insatiable need to give love, interrupted by Alan’s death, manifests itself in Charlie’s self-destructive tendencies toward isolation and binging. In one way or another, every character in the film – Ellie, Mary, Liz, the missionary – is held to their own sort of self-inflicted captivity and grief. However, Charlie is the only one to accept his struggles and choose to live positively.

Audience members are also asked to endure this captivity with him, almost never seeing outside of the small Idaho home in which he spends all his time. In this way, The Whale encourages audience members to see the world through Charlie’s eyes. We experience the bleakness and repetitiveness of his life through the dullness and stagnancy of the shots. Aronofsky’s use of natural light in Charlie’s home – or the lack of it – is key to our understanding of Charlie’s embarrassment with the state of his own life. The inclusion of Charlie’s virtual lessons using a Zoom-like platform is sure to remind viewers of their own days in mid-pandemic Zoom school and the ways in which technology can make it so much easier to hide the parts of us we cannot bear to confront.

While its story is undoubtedly heartbreaking, The Whale’s breathtaking performances and unmistakably human dialogue are enough to warrant purchaing an extra box of tissues to make it through.

The Whale will run at Images until Thursday, Feb. 9.