First weeks of January bring milder weather to the Berkshires

January 25, 2023

Until a storm blanketed the College in nine inches of heavy snow Sunday night, Winter Study had lacked one of its most characteristic features. The first two weeks of January included just one day of measurable snowfall in Williamstown, totaling only 0.3 inches, according to data provided by the College’s Environmental Analysis Lab.

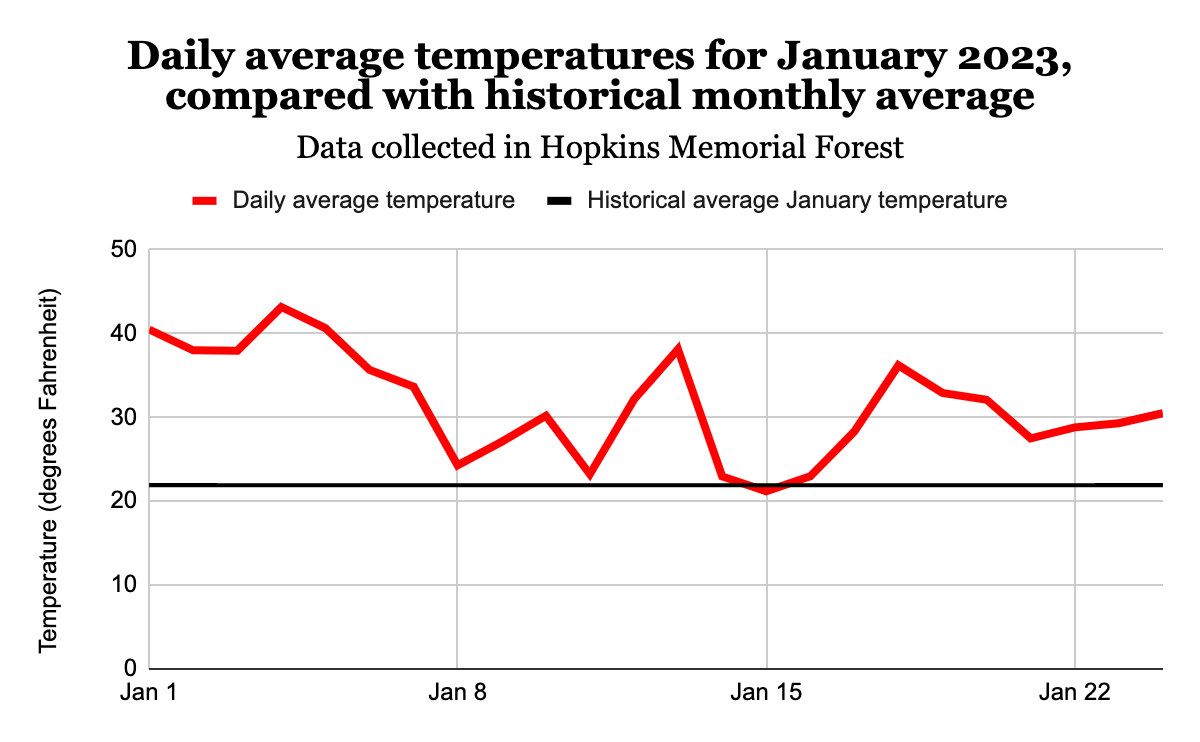

So far, this low-snow season has thrown a wrench into local winter recreation and offered a glimpse into the future of New England’s winters, which are projected to become shorter and less consistently snowy as the Earth warms. The average temperature in Williamstown so far this year, as of Jan. 24, has been 31.5 degrees Fahrenheit — nearly a full ten degrees warmer than the historical average temperature for January.

“The Nordic team has been adversely affected by the lack of snowfall,” Nordic Skiing Head Coach Steve Monsulick wrote in an email to the Record. “We had to change our local training venue from our normal location at Prospect Mountain to Jiminy Peak, travel to the Dublin School in New Hampshire, or just go running from campus.”

In the team’s first two weeks of the season, he continued, organizers of competitions around New England changed the techniques and venues of various races to accommodate for low-snow conditions. Two races were shortened from five kilometers in length to 2.5.

Professor of Geology and Mineralogy Emeritus David Dethier, who sits on the board of Prospect Mountain Nordic, a cross country ski center in Woodford, Vt., commented on the region’s decreasingly snowy winters. He has been working to raise money for artificial snowmaking, which Jiminy Peak uses to supplement — or replace — natural snow. Dethier has been collecting data on weather conditions since his arrival at the College in 1982, and in an interview with the Record, he highlighted one wintertime trend that he believes has become more common in recent years.

“I refer to them as ‘death thaws,’” he said. “These striking thaws where we’ll have temperatures in the 50s for several days have meant that the snow on the ground is theoretical.”

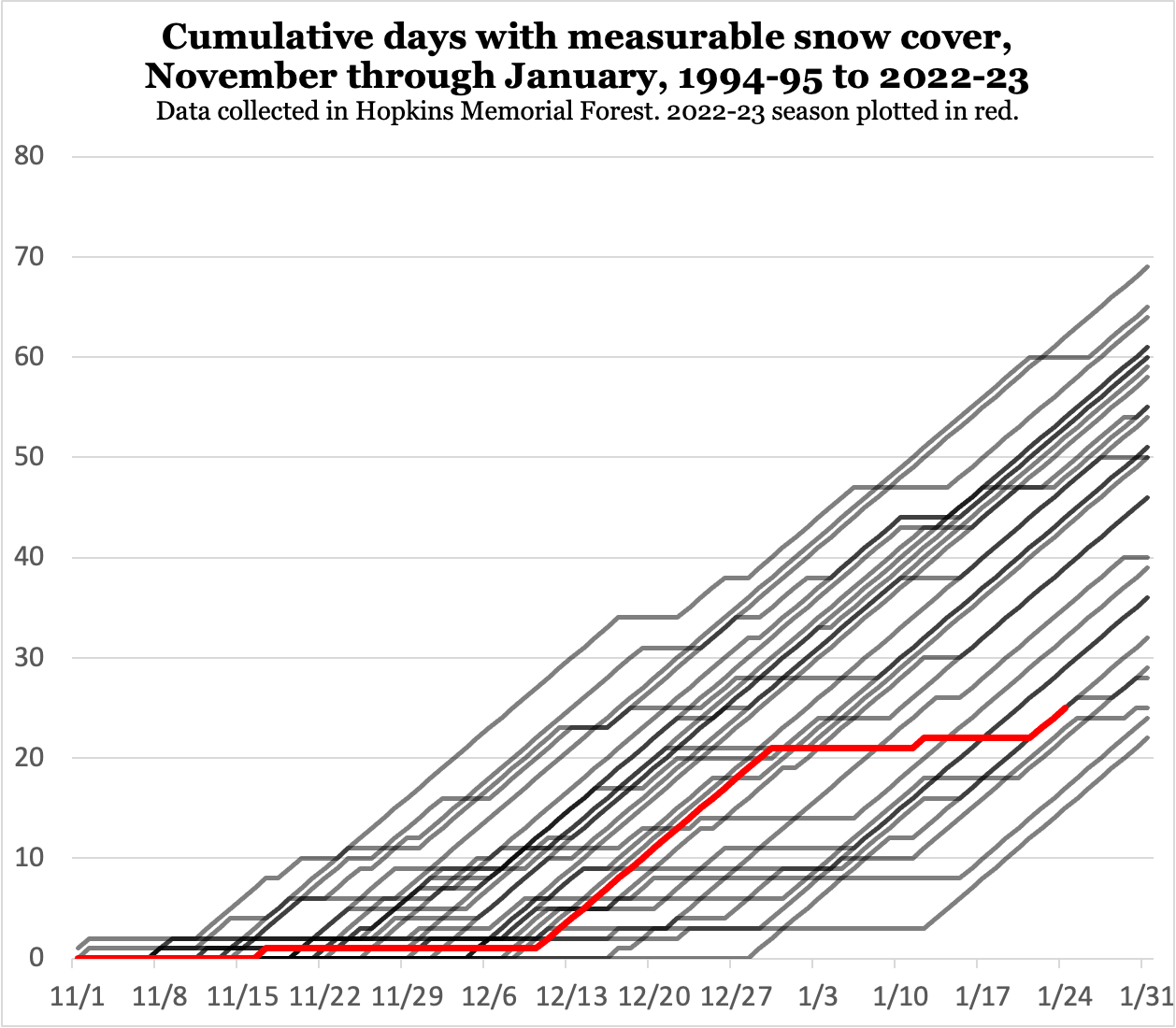

This season, snowfall in Williamstown started at a comparatively normal rate. By Christmas, total snowfall was on par with the mean amount for that time of year, according to the Environmental Analysis Lab’s records of snowfall in Hopkins Memorial Forest, which date back to the 1994–95 season.

Then, around New Year’s, one such “death thaw” occurred. Daytime temperatures climbed well above freezing. The existing snowpack, which had accumulated throughout the month, melted into the earth. For several weeks thereafter, not much fell to replace it. As of Jan. 23, Williamstown’s total snowfall was underperforming the average year by 22 percent.

One person’s experience of a big thaw — or a big blizzard — may not say much on its own about where the climate is headed. Since weather naturally varies to a large extent from year to year, Dethier said, changes in climate can be understood through more objective means, such as when the skiing season ends, or when springtime temperatures arrive. Then, of course, there are the numbers.

Over the last 30 years, Environmental Analysis Lab data indicate that the Town has seen a decline in the number of days that have had more than an inch of snow on the ground — a reasonably intuitive measure of how wintry a winter has been. Williamstown has also experienced a decrease in seasonal snowfall. These observations line up with a broader consensus about the warmer, less snowy, fate of New England’s winters.

When snow fails to fall for weeks, it is easily apparent to us. What may be more difficult is to observe a shift in averages; what does, say, a gradual decrease in annual snowfall over decades feel like? Armed with an understanding of such trends, one can place weather events in their proper context. Blizzards that provoke all-campus emails may continue to happen — but less often. “Death thaws” that consign the ski teams to other practice locations may grow more intense or familiar. And there will still be days when Paresky lawn is coated in snow — just fewer of them.

Dethier provided another line of thinking for those hoping to understand how today’s seasonally inappropriate weather relates to tomorrow’s climate. “It’s being visited by the future climate,” he said, “for days or months at a time.”