Vigil honors Ürümqi fire victims, supports protesters in China

December 7, 2022

Last Thursday evening, a group of approximately 10 College community members held a vigil outside Paresky, shielding candles from frigid gusts of wind. The event commemorated the victims of an apartment fire in Ürümqi, a city of 4 million in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China. On their own, this stated purpose and the vigil-goers’ presence conveyed a clear message, but equally significant was what had been left unsaid.

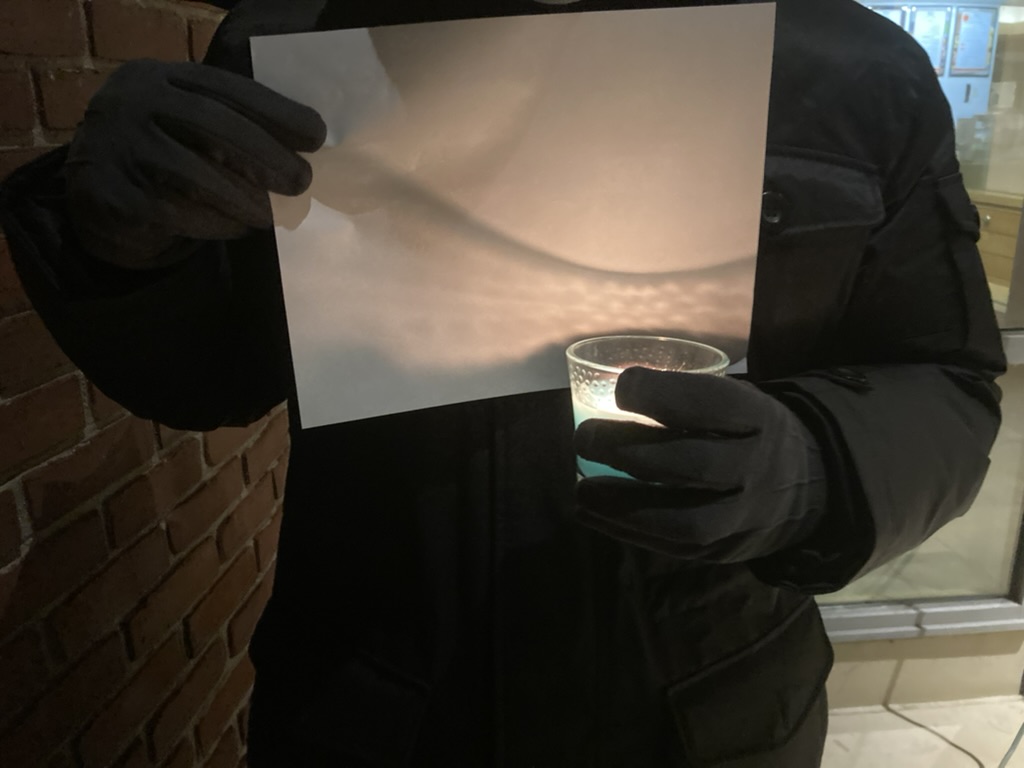

No students’ or organizations’ names were included on the posters that advertised the event around campus. The Daily Messages entry, which encouraged students to come bearing candles, flowers, and sheets of paper, was submitted without any names or contact information attached. The sheets of paper, which most attendees held in their hands, were blank. No attendees expressed willingness to be photographed or quoted in an identifiable way, and the Record granted interviewees in this article anonymity due to their fear of retribution from the Chinese government.

According to the Daily Message, the event was held in solidarity with a wave of protests taking place across China after the Ürümqi apartment fire. The fire killed at least ten, and many have alleged that local COVID-19 policies exacerbated the harm — though Chinese governmental authorities have maintained otherwise. While the fire was the catalyst, the Chinese government’s stringent “Zero COVID” policy — which placed much of Ürümqi under lockdown for more than three months — and its opposition to freedom of expression have been included among the grievances listed by protesters around the country. Blank, letter-sized paper, wielded by protesters to criticize the Chinese government’s censorship, has become one symbol of their movement.

One attendee — a Chinese international student — said that they attended the vigil out of a desire to express solidarity with protesters within China. “For those who are physically abroad, [protesting] will be safer,” they explained. “But still, there is a high risk incurred.”

“This Ürümqi fire happened during Thanksgiving, and I was with a few other friends from China,” they continued. “We just kept talking about it because there were so many of our peers — young people — protesting, and some of them [were] being arrested by the police… I’m still connected to China and everything that has been going on.”

A second attendee, a Taiwanese international student who has lived in China, was granted anonymity to avoid repercussions that could affect future travel to China. “When I saw the news [of the fire], it just broke my heart,” they said. “Ürümqi and people in the Xinjiang region have just been through so many waves of oppression and cultural erasure — just so many awful campaigns by the CCP [Chinese Communist Party].”

Xinjiang has been the site of mass detentions of Uyghurs and other Muslim ethnic minority groups, which Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have characterized as “crimes against humanity.”

A third attendee, who lived in China for a number of years and was granted anonymity because they still have family there, said that friends back home have faced retribution for speaking out during the protests. Some have had their social media accounts suspended.

“One of my friends just got stopped on the street, and a police officer asked to check her phone and found that she had a VPN [and] Instagram, so [he] took her in, got her information, asked for her parents’ information, and made her delete everything on the spot,” they said. “I would hope that at the end of this, freedom of speech is at least in some part effectualized within China.”

The first attendee said that they had witnessed “about 90 percent of relevant posts” on Chinese social media apps being taken down.

Several of the attendees stressed the significance of student involvement in the protests, both within and outside China. “I’m here for two reasons,” a fourth attendee said. “One, to memorize what happened in Ürümqi, to pay respect for the loss of lives. But another reason I’m here is for the generation of college students in China. I think they are very courageous.” The interviewee was granted anonymity because they intend to travel to China in the future.

In addition to these immediate aims, some participants placed this outbreak of widespread protest — a rarity in modern China — within a broader historical context.

“Lots of people [in China] just stopped believing in changes after so many years,” the first attendee said. “I believe that many times people are unsatisfied — upset by the Chinese government’s policies, authoritarianism, [and] its oppression. But people stopped believing in changes, and they didn’t think anything was going to happen with their own effort, and I just want to say: Don’t do that. If all of us start to believe that nothing will eventually change, then nothing will change.”