Williams alums fight for better pay, housing in UC worker strike

November 30, 2022

Forty-eight thousand postdoctoral researchers and graduate student workers across the University of California (UC) system have been on strike since Nov. 14 — the largest strike of the year in the United States and ever at any academic institution. The graduate students, who all work for a UC school while taking classes in pursuit of an advanced degree, are already unionized with the United Auto Workers (UAW), but they now seek better pay, housing, and a fair bargaining process with the UC system. Williams alums involved in the strike spoke to the Record about their compensation and housing troubles across the UC system, but they also shared a sense of hope for a more equitable future.

The average UC graduate student worker’s pay is $24,000 per year, about half the $54,000 minimum that the union is demanding as reasonable compensation given the cost of living. Furthermore, the strikers consider university-provided housing to be limited and unreasonably priced. The strikers’ other demands include increased support for working parents and people with disabilities, public transit funding, and visa aid for international students. Union leaders have filed 25 unfair labor practice claims against the UC with the California Public Employment Relations Board, and the board has found evidence of unfair practice in six cases. On Monday, 300 faculty members ceased to teach and grade their courses in support of the striking workers and out of necessity, given the integral role the strikers play in classroom functions. However, these faculty make up only a small percentage of the more than 11,000 employed by the UC, though more may sign on to the work-stoppage pledge.

The University of California has asserted that its compensation is fair for the part-time work that graduate students perform, that their stipend is high among public universities, and that the strikers are asking for private university-level pay that the UC cannot provide. The UC claims to be in good-faith bargaining negotiations on a daily basis with the UAW and making progress toward a deal.

Since the strike began over two weeks ago, daily life on UC campuses has changed, demonstrating the integral roles that graduate students play in keeping the school running. Ry Brennan ’12, who went by Mariah Clegg while a student at the College, is a sociology doctorate student at UC Santa Barbara. Brennan teaches an undergraduate sociology class, but during the strike, they’ve replaced typical class time with alternative kinds of education. “A lot of graduate students and undergrads are … marching, holding signs, and walking around campus, trying to demonstrate that business as usual has ceased,” they said. “I’ve been hosting teach-ins on topics like what the strike is about, mutual aid, and intersectional organizing.”

Since many graduate student workers evaluate undergraduate work, the strikers can exercise power by withholding grades until their demands are met, Brennan explained. “This is [done] with the understanding that the UC really does not care about the education of students,” they said. “They really don’t care if students walk away from classes having learned anything. They don’t even particularly care if classes happen. They care about students being able to get credit so that they will continue to enroll so that the UC can sell its actual commodity, which is the certification of having gone to a UC.” The conflict would have to end prior to Dec. 14 for undergraduates to receive their final grades.

Katherine Hatfield ’22, who is pursuing a doctorate in UC Berkeley’s department of ancient Greek and Roman studies, is a first-semester graduate student and doesn’t work for the UC yet — but many of the other students in her classes do. To accommodate those student workers, two of her classes have offered optional Zoom sessions. “One of my classes has been in a cafe,” she said. “Most of our class [doesn’t] want to cross the picket line, so it’s sort of a symbolic action.”

Though Hatfield is not a worker yet, she is still part of the union and voted to authorize the strike. “I can see how hard my colleagues who are teaching are working, and I don’t think [the increase] that the UC is offering is going to be enough,” she said.

The increase that Hatfield mentioned was also a focus for Brennan. The UC website outlines a range of pay increases ranging from 4 to 10 percent depending on the position, and the current rate of inflation is 7.7 percent. “What the UC has been offering — and they call this generous — is almost meeting our inflation rate in terms of a pay raise,” Brennan said. “Barely keeping up with inflation is their supposed ‘generous’ offer.”

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines a person as rent-burdened when they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing. The UAW claims that 92 percent of graduate students fall into this category. Hatfield’s experiences at UC Berkeley support this estimate — at a department meeting, the union representative shared the 30-percent benchmark with the graduate students. “Everyone laughed,” Hatfield said. “Everyone is paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent.”

According to Brennan, last year as a graduate student researcher, they were making around $11 an hour and spending about 70 percent of their earnings on rent. This year, teaching an undergraduate class, they are spending 50 percent of their income on rent and making $15 an hour. While the students are considered part-time workers and the UC pays them accordingly, many of the graduate students still deem the pay inadequate.

“The University says it’s a part-time job,” Hatfield said. “It is and it isn’t, because you don’t have time to do another job.”

Across the board, inadequate pay compared to high housing prices was a key concern. EJ Toppin ’10, a graduate student at the UC Berkeley Goldman School of Public Policy from 2016 to 2018 who now works as a researcher and policy analyst at the UC Berkeley Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, recalled his stipend and housing options in graduate school as seriously limited. “The stipend is barely enough to live on,” he said. “I lived in a house with seven other people.”

Robert Cooper ’06, a staff scientist at UC San Diego’s Bio Circuits Institute, is a member of a union of academic researchers also on strike. He loves his job in academic research, he explained, but the pay makes it hard to justify. “Compensation is significantly below what one could find on the private market, and certainly below what it takes to comfortably have a family in San Diego,” he wrote to the Record. “I’ve been able to stay in academic research because I was lucky enough to get hit by a car and put a resulting insurance settlement in the stock market at the right time of the economic cycle.”

For those without insurance payouts, the options are limited. Brennan, like Toppin, lived in close quarters — their house in Santa Barbara before the pandemic was home to seven other people and did not comply with fire code. Brennan was evicted during the pandemic; the federal eviction moratorium didn’t apply to them because they lived in a single-family dwelling. After moving into their partner’s housing in Long Beach, Brennan worked from home — a five-hour train ride from UC Santa Barbara — and still used 50 to 70 percent of their income to pay rent.

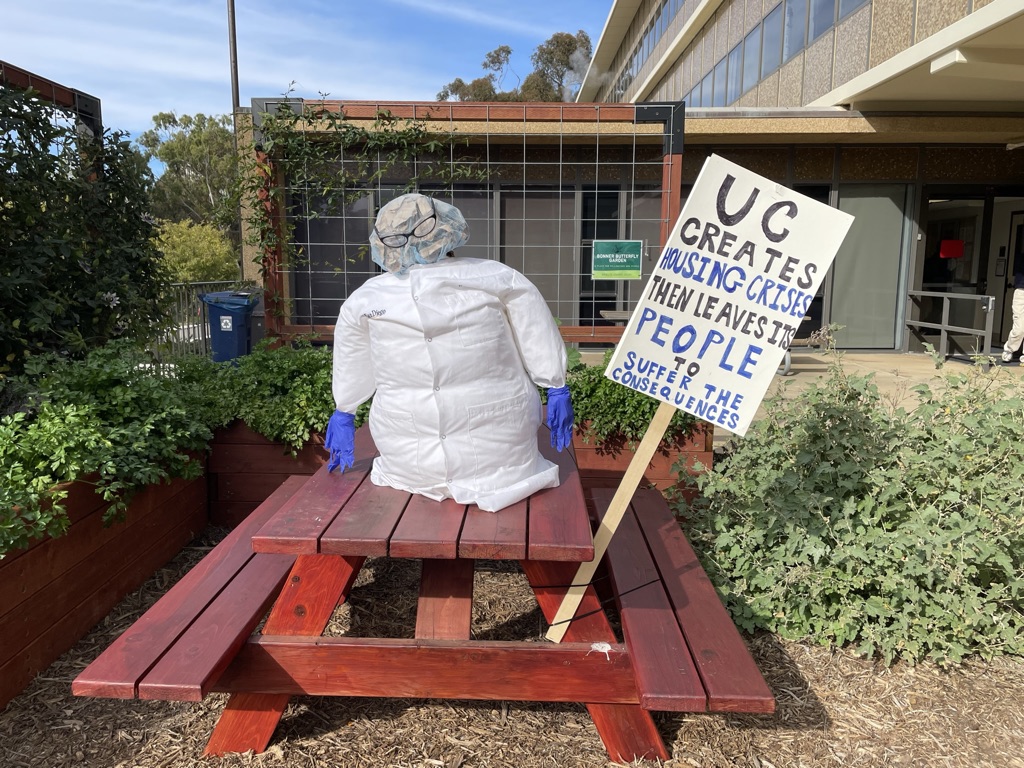

While the housing crisis is occurring across the country, Cooper highlighted the UC’s complicity. “It’s important to recognize that this isn’t just a case of UC being caught in the same housing crisis as the rest of California and the country,” he said. “They actively make the housing crisis worse around their campuses by expanding too fast without providing student housing.”

Another point of contention between the strikers and the UC is the classification of graduate student workers as students, though producing academic scholarship and functioning as educators are key parts of their roles. “Calling grad students ‘students’ is really an anachronistic way of categorizing them,” Cooper said. “They really do a large amount of the teaching and most of the actual research, which together bring in a lot of revenue through tuition and research grants, so in actuality they’re critical employees. Calling them students worked when they were largely nobles supported by family wealth, or when cost of living wasn’t so bad, but if we really want to open higher education to a more diverse set of backgrounds, we need to move toward a new way of thinking about graduate school.”

Brennan shared a similar frustration. “Before being a graduate student, I was a segway tour guide,” they said. “That job pays more than what I’m doing now … and I’m actually doing the work of educating all of the people who have to pay tuition [at] the UC.”

Strikers also navigate a complicated, state-wide bureaucracy within the UC, a system that operates differently from Williams, Brennan explained. Decisions are not made on a campus-by-campus basis, but rather at the University of California Office of the President by regents and other bureaucrats with varying connections to education.

“Every single person at the University of California, Santa Barbara, could be in favor of raising graduate student pay, and we still could not get that because we are just one part of this massive bureaucracy that we have no control over,” Brennan said. “That’s very, very different from a Williams scenario, where if there were a massive student uprising, it would be very hard to ignore.”

However, even within the UC bureaucracy, the power of 48,000 workers on strike has made waves. Toppin is energized by the strike and hopes that current workers are able to secure the support he never received from the UC when he was a student. “I was a part of that union when I was a student, so I’m clearly behind them,” he said. “I hope that they are able to win the list of demands that they have.”