Yik Yakkers at the College post for upvotes and laughs

November 30, 2022

Whether your Yakarma stands at a mere 82 or you’ve broken into five digits, you’ve probably at least heard fellow classmates discussing the latest Yik Yak post that made them chuckle.

Yik Yak — an app where individuals can anonymously post to a five-mile radius — has gained traction at the College, and nationally, over the past two years since its re-release. (YikYak’s first iteration was released in 2013, but it was shut down in 2017 after a series of issues surrounding bullying on college campuses.) The emoji profile pictures, which are randomly assigned to each user, hold an air of mystery. And on such a geographically isolated campus, Yik Yak in Williamstown has a particularly intimate feel, since the majority of potential posters are students.

Who are the people that choose to spend their time building their Yakarma — the arbitrary points doled out to frequent and successful Yik Yak users — and how have they crafted strategies to get the most upvotes? We spoke with three students to find out.

Sam Drescher ’26, Olivia Johnson ’26, and Lola Kovalski ’25 are three such users. Drescher and Johnson have scores of about 1,000, and Kovalski, who has not posted since the spring, has a Yakarma of 3,156.

Kovalski said that she started posting to Yik Yak because it didn’t seem very difficult. “I think someone showed me something funny on it,” she said. “I was like, ‘I could do that.’”

Johnson said she heard about the app in her first few days on campus. Because of a “desire to do well on Yik Yak, accruing Yakarma became a very fun side quest,” she said.

Each takes a different attitude toward posting. While for Johnson it’s a “side quest,” for Drescher, “You kind of just go on there and you see what works and you see what lands,” he said. “I’ll admit sometimes the stuff doesn’t land, but that happens to everyone.”

Kovalski, on the other hand, was much more focused on posting content that would resonate with students. “I set out to game Yik Yak and see how many upvotes I could get and if I could accurately predict what would be popular,” she said.

What kinds of posts worked? “Lots of depression, SSRI remarks, and just general mental depravity — because it’s resonant,” Kovalski said. “I think people get satisfaction in knowing that there are other people doing worse.”

Kovalski also “started experimenting with different voices.” When she posted “Smiling at her texts, SOS lads” (40 upvotes), she was embodying a “last row econ guy” who’s “typically cold but finally likes a girl,” she said.

“I inserted myself in the group and spoke as if I was a member of the group,” she said. “It’s just the archetypal voices and characters of this college.”

Over the course of a week in October, these were some of the most upvoted posts:

English prof: what does this passage mean?

Me: it describes the juxtaintrasexualqueeriosity of how 9/11 was an inside job

Prof: Finally a student who f*****g gets it (73 upvotes)

“Your yak was upvoted for the first time” yeah I know I just did it (59 upvotes)

“profs don’t assign homework over parents weekend right?” — my mom (56 upvotes)

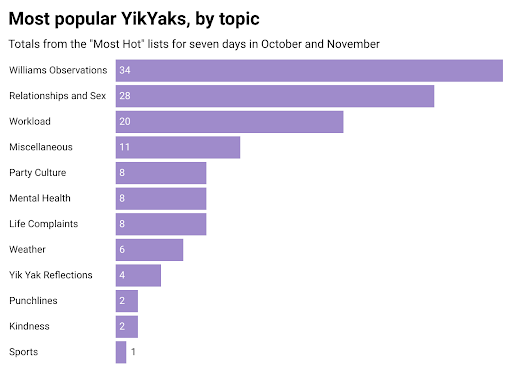

While these were most popular, students use Yik Yak to share many kinds of thoughts: observations about events at the College, comments about relationships and sex, and musings — usually complaints — about workload.

Kovalski, however, mostly saw YikYak as “an anonymous place where you can post your thoughts and maybe get a little giggle.”

Yik Yak’s anonymity, ease of access, and semi-public nature have also given a platform to hate speech and harassment. Earlier this month, Ashley Shan ’26 wrote about racist content on the platform in an op-ed for the Record. “Anonymity does not immediately equate to evil,” Shan wrote, “but when anonymity lends itself to slurs and racist speech, it’s clear that it provides a shield for users on the app.”

Last May, Professor of Psychology and former Dean of the College Marlene Sandstrom emailed the student body after multiple students were harassed by name on Yik Yak.

Johnson agreed that the app came with its dangers. “[Yik Yak] lends itself to being really unfiltered, really unhinged, and avoiding all consequences,” she said. “That brings out some really nasty sides of people.”

“It can be a way for people to get their word out there if they feel like they don’t have any other outlet,” Drescher said. “A lot of very negative stuff can happen when people aren’t held accountable for what they’re saying.”