Anamnesis documents Black experience at College

November 9, 2022

From Sept. 27 until Nov. 7, students entering and exiting Sawyer library could look at Anamnesis, an archival project created by Nasir Grissom ’23 that featured archived photos of Black student life at the College.

Grissom’s display in the library is an extension of a personal photography project that he and Samuel Ojo ’22 created in the spring of 2022. While the intention of the project was to discover, document, and record the Black experience at the College, Grissom realized he wanted to preserve and present a sense of collective memory of the Black experience as well. He hoped that his work would be widely visible and that it would inspire students to look into the College’s archives themselves.

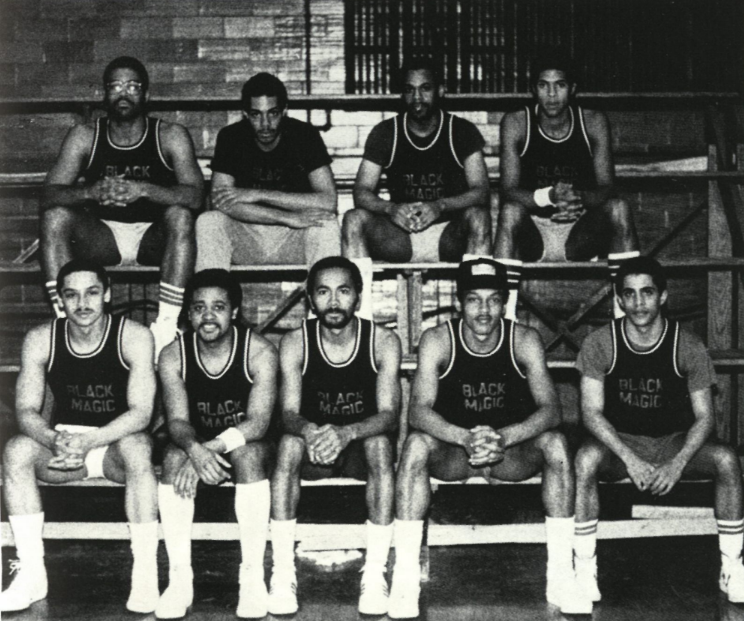

During the fall of 2021, Grissom and Ojo workshopped several different creative projects to showcase the experiences of Black students at the College. While browsing Unbound, the online platform the College uses to document and organize archives, Grissom stumbled across Genesis, a Black student yearbook published in 1989, and the Black Student Union (BSU) yearbook from the 2005–06 academic year. Both yearbooks document Black life at the College through pictures of students and activities.

While reading through the archives, Grissom realized that the current narratives of Black life at the College focus more heavily on student activism since the 1969 Hopkins Occupation. “At Williams, as a Black student, what you’re constantly kind of fed is this Hopkins Occupation narrative and like this narrative of student activism, which I think is a very siloed experience,” he said.

Grissom became frustrated that his intensive online search seemed like the only way to engage with the historical efforts of the Black community at the College. “I ruminated on it for a while,” he said. “Then Sam and I started talking about wanting to do a photo project documenting all Black students on campus in the spring of last year.”

In the winter, Ojo and Grissom, who has experience with photography and graphic design, started their photo project titled Anamnesis. “All we wanted to do was take pictures of Black people that were creative and fun and showed a dynamism,” Grissom said. “We wanted to show presence, because we felt like that was lacking from at least the online archive.”

Anamnesis was displayed in a gallery on Water Street last spring, and the photos will be incorporated into a book by the end of this semester. Grissom and Ojo photographed about 65 percent of the Black students on campus and conducted interviews with Black faculty and staff. The book will also incorporate student poetry and art.

Grissom then decided to dive further into the history of what he had found over the past year. “Since I’m a history major, I was like, ‘What was actually happening?’” he said. “‘Why were these books created?’” Over the summer, Grissom scanned print works that documented Black perspectives at the College and uploaded them online. Through reading the archives, he discovered that the College’s Afro-American society had an admission committee, which would create documents called “Black perspectives” or “Black reflections,” some of which were created in an effort to convince prospective Black students to apply to the College. Grissom ended up creating an archival collection that focuses on the history of Black life at Williams — also titled Anamnesis — which was on display in Sawyer from Sept. 27 to Nov. 7. Now, Grissom is working to put together a book that showcases the photo project from last spring and is reminiscent of past iterations of ones found on Unbound.

Grissom stressed that he does not consider the work a yearbook. The project is instead intended to be its own archive: a documentation of Black life at the College in this moment, intended for the benefit of future students looking back at this time.

He also noted that student efforts to make these yearbooks had not been consistent over the years. “The last one was maybe 2010,” Grissom said. “That’s a 12-year period. What happened?”

Kim Dacres ’08 noted similar difficulties in maintaining consistency when she edited the 2005—06 BSU yearbook. “I’m sad, but I’m not surprised that these efforts have dwindled over time, because those students’ efforts were severely overlooked and undervalued by the institution,” she said. “I imagine it was difficult for future generations of Black Williams students to sustain that kind of energy for a community and also graduate with joy and a decent GPA.”

She noted that the creation of the 2005–06 BSU yearbook, which was entirely student-directed, entailed an extensive amount of work. “The burden of planning and executing largely fell on Black student leaders, not the College,” she said. “It was another major or a part-time job. It was a lot of work, but the yearbook was the way to celebrate us and our labor and a way to pass on a legacy.”

Grissom said that while he and Ojo received a Towards Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity (TIDE) grant for this project, it was necessary but difficult to maintain institutional support for the work beyond a one-time grant, especially if students wanted to continue that work in the future.

Fortunately, Grissom said, there is an ongoing effort to continue documenting and sharing. “There are students with the Black Student Union who are working with the [Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion] on trying to keep this going,” he said. Grissom also noted that some students from other affinity groups have told him about their interest in starting their own photo projects.

“I think that’s really one of the biggest things that came out of [this project],” he said. “People are now starting to dive into their histories, trying to document themselves and figure out how their identity is nested within campus and how they can preserve that. That’s really what it is [about]. How do you preserve your history?”