Crosswalks, signs, and lights: How the Town tamed Route 2

October 5, 2022

Though the fact that Massachusetts Route 2 bisects the College is likely one of the first things someone new in town would notice about the built environment, it quickly recedes into the background of daily life. “Stop, look, and wave” becomes reflexive; the miniature traffic jams that occur between classes start to feel mundane. It would take a lot for the road to feel unfamiliar — but quite a lot took place in the fall of 1993.

In an October 1993 Record article, then-Select Board Chair Anne Skinner said that roughly one person was getting hit by a car every year on the road. As a result, the Select Board voted to start enforcing jaywalking laws and remove some of the crosswalks in an effort to rein in pedestrian traffic on Route 2.

A couple weeks later, these laws were put into action after a car struck a first-year College student on Route 2, sending her to the hospital. She had been crossing the street from Hopkins Hall to Lasell Gym — “feet from where a crosswalk had been removed only weeks ago,” the Record wrote. The Williamstown Police Department filed jaywalking charges against her.

Then, in November, another student was hit while using one of the crosswalks that still remained after the October changes. “You still have to cross the walks defensively,” then-Dean of the College Joan Edwards said when the Record asked her for comment. “You have to be absolutely certain that the cars are stopping before you step out in front of them.”

At this point, it is probable that some on campus were sympathetic to a view expressed by Sidewalk Committee and Select Board member Chester P. Soling in a November 1993 letter to the editor:

“Williams College has been here for 200 years,” Soling wrote. “I suppose that for most of this period Main Street has existed. At some point, the street became the Mohawk Trail and then Route 2, an interstate [sic] highway. What has been the college’s reaction to having a major highway cutting through the center of their school? They have blithely gone ahead and continued to build major buildings on both sides of the road.”

Blithe or not, the College and highway weren’t going anywhere — and when it came time to draft the Town’s 2002 Master Plan, planners recognized a need for updated pedestrian infrastructure. The plan recommended a major intervention: installing raised crosswalks at either end of the stretch of Route 2 that runs through the heart of campus. Part crosswalk and part speed bump, these were intended to “reduce vehicle speed, improve pedestrian visibility and emphasize pedestrian priority, and reduce pedestrian-vehicle accidents.” Though they didn’t get built, other, more recent, innovations appear to have reduced the rate of accidents.

The highway today

Two decades later, crossings on Route 2 are now punctuated by the blinking yellow lights and automated voices of Rectangular Rapid-Flashing Beacons, which were affixed to reflective signs at each crosswalk in 2019.

Williamstown Chief of Police Michael Ziemba believes these innovations bear much of the credit for a decrease in the frequency of student pedestrian accidents on the street. “The driver’s gonna see those lights flashing before they even see that there’s someone crossing the road,” he told the Record, adding that he was strongly in favor of such infrastructural safety improvements.

In Ziemba’s view, the new LED streetlights along the corridor — an effort initiated by the Town’s CO2 Lowering Committee — provide better visibility for motorists.

According to Andrew Groff, the Town’s community development director, coordination between the College and Town had improved in recent years, which has led to progress on safety. He also pointed to another calming influence on traffic: trees.

“We’ve been aggressively pursuing [state and federal funding] to ensure that we maintain tree cover on the Town green,” Groff said. “It’s important for a number of reasons, including slowing traffic.” The idea is that motorists, feeling more hemmed in by the landscape, will proceed with increased caution.

According to a recently released Existing Conditions Analysis for the upcoming Comprehensive Plan, over the past ten years, “Main Street (Route 2) had a total of 458 reported crashes which included 72 injuries, and 1 fatality.” Thirteen of these crashes involved pedestrians, and 12 involved cyclists. (These numbers were tallied for the entire Williamstown portion of Route 2, which encompasses far more than the segment through the College’s campus.)

The future of the Town’s streets

“It’s 2022,” Groff told the Record while sitting in his office, where bound copies of past town plans line the shelves. “It’s time to realize that there are more modes of transportation than just motorized vehicles.”

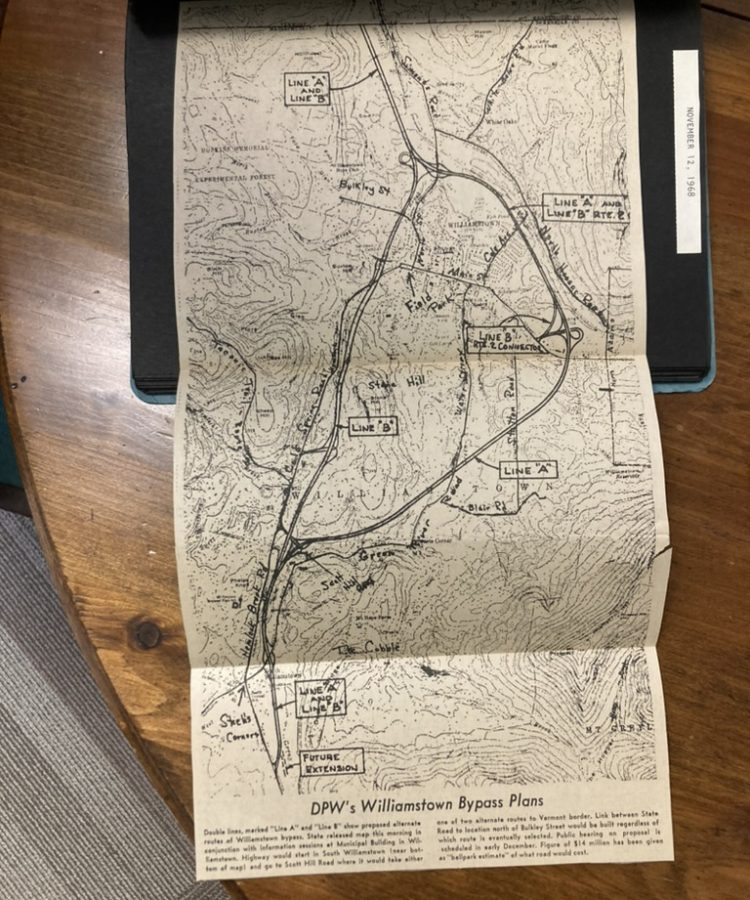

Pulling out one of those binders for emphasis, he showed off a 1960s plan to construct a freeway bypassing the College and Town center. Needless to say, it was never built.

Nowadays, those in charge of the Town’s roadways are seeking to improve the pedestrian and cycling experiences, which sometimes means reducing vehicle speeds. “If you’ve looked at other communities and how traffic and pedestrian safety is now being thought about … it’s more about changing roadway geometries to physically slow cars,” Groff said.

Stephanie Boyd, a co-chair of the Comprehensive Plan Steering Committee, has additional priorities on top of road safety. “If we were designing the town and the campus today, how would it be different?” she wrote in an email to the Record. “We’d want it to be safe, easily accessible for everyone, and to minimize our environmental footprint.”

While motorists do face some inconveniences — such as more stopping and slower speeds — from so-called traffic calming projects, both Groff and Boyd said they believe that future efforts would not face much pushback. The “Existing Conditions Analysis” mentioned earlier outlines what these efforts may look like.

“It is clear that there is strong interest in reimagining the existing automobile dominated transportation system as a complete and green street network,” the document reads. “Investments made in bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure should include safety enhancements, outreach and education efforts, covered storage, and other amenities that support this shift in transportation choice.”

Elsewhere in its 182 pages lies a suggestion for a transformed streetscape. “The addition of street trees, the narrowing of lanes, the extension of pedestrian crossing areas, and other design strategies could help Williamstown slow traffic in the more densely developed portions of the community, and accommodate pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure safely.”

It’s a far cry from the fall of 1993.