Heating and powering the campus: It’s a steam effort

September 21, 2022

The steam tunnels of the College have been the subject of lore for generations of students. Beyond the campus myths about a secret network of passages under the campus, these tunnels have a much more practical function: heating the water to our showers, warming the radiators in our dorms, and even charging our devices.

Take a look over the bluff behind Prospect House and you’ll see the source of this steam — a large building with a tall chimney sticking out from it. It’s the College’s central heating plant, and within its walls are nearly a dozen boilers, an electric turbine, and a host of other equipment designed to heat and power the entire campus. It’s the only College office besides Campus Safety Services that is staffed 24/7.

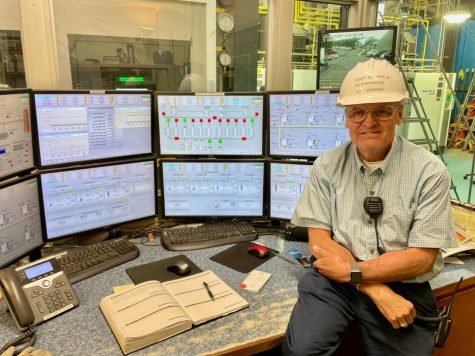

Over the summer, I toured the relatively unknown College Heating Plant and spoke with its manager, Gary Bonafilia, the man behind the steam.

Overview and origins

Nestled in the Berkshires, the College has wrestled with the problem of keeping warm since its founding. These days, when the temperature starts to fall below 40 degrees, the central heating plant swings into full gear, running its main boilers to produce over 1 million pounds of steam per day. This steam travels through 3.5 miles of steamlines and tunnels to 74 buildings on campus. At each building, steam passes through heat exchangers, which use the steam’s energy to heat water for showers and supply warmth to each building’s network of radiators. After the steam condenses into water, it returns to the central heating plant.

But it didn’t used to be this way. Prior to 1901, fireplaces were the primary source of heat in many of the College’s buildings. That year, the College built its now-superseded coal-fired central heating plant. In the colder months, two workers shoveled coal day in and day out to fuel a boiler, producing steam to keep the campus warm.

With a few efficiency and sustainability updates, the College has used the same basic principle — using fuel to produce steam — to warm the campus ever since. By 1934, the College had grown substantially and built a larger central heating plant — the same one in use today.

Originally using coal and then No. 6 fuel oil, the plant now burns natural gas as its primary fuel source and diesel fuel as its backup. In the dead of winter, according to Bonafilia, the College burns up to 1,800 dekatherms, or approximately 1.8 million cubic feet of natural gas, per day.

Electrical cogeneration

“Central plants are used by large colleges and universities, military bases, medical centers and large corporate campuses,” industry magazine Plant Engineering notes. “Though they are complex and costly to operate, they create efficiencies that over time save money.”

By centralizing heat generation across campus, the College is able to harness much of the energy it would otherwise waste through chimneys by creating electricity.

“Electricity is our by-product,” Bonafilia said. “The main product is what we’re putting out to the campus for your heat and your comfort, so the electricity is almost free.”

The plant takes freshly-generated steam and warms it with excess heat from the boiler, which it them runs through a steam turbine to generate electricity before it flows across the campus.

“We produce, in the winter, about 70 percent of the campus electric load,” Bonafilia added. And this energy has environmental benefits as well.

“For every kilowatt that you produce in house there’s a [carbon dioxide] reduction,” Bonafilia said, describing the benefit of sourcing electricity from the College’s plant rather than the power grid.

Even though the steam condenses into water as it heats the campus, the condensed water still retains a lot of its heat when it returns to the plant.

“To get that up to steam temperature again means less BTUs [a standard thermal unit] I have to add,” Bonafilia said, a process made more efficient still by the College’s use of otherwise wasted heat in the plant’s exhaust gasses to heat the water before it is pumped into the boiler.

According to Bonafilia, with the help of electrical cogeneration and heat recapturing, the plant is able to operate at an overall efficiency of 83 to 85 percent when it is in full swing — meaning only around 15 percent of the energy burned is lost and thus unable to be used for heating or electrical generation.

Year-round heat

“Most of the buildings on campus — the larger buildings — have what’s called an auxiliary boiler that [is] used for summertime steam for hot water,” Bonafilia said. And so, up until 2017, the College was able to forgo running the central heating plant from May through September, using that time to conduct maintenance.

However, beginning in 2017 with the construction of buildings without auxiliary boilers, the College began to run the plant year-round and installed eight micro-boilers in addition to the primary boilers. These allow the College to reduce output during the summer, when there is less demand for heat, and serve as backups during the winter.

“My goal is to make this place better than I found it”

Beginning his career as a boiler technician in the U.S. Navy, Bonafilia has spent decades working in and later managing plants for the government, utilities, and private businesses before beginning at the College in 2014.

Commuting over an hour and a half to Williamstown every day, Bonafilia’s mission is straightfoward. “When I leave here, which won’t be too long, a couple years, my goal is to make this place better than I found it,” he said.

Perhaps greater than Bonafilia’s pride in the plant is his pride for the staff who man it. Three years ago, the heating plant unexpectedly shut down. Bonafilia was not in on that day — he had a pressing appointment that kept him away — but his staff were able to run the plant without computerized automation, all by themselves, with minimal guidance from him over the phone.

“The sign of a really good manager is not the fact that he’s there during every incident but that he’s trained his people enough that they do without him… Just the fact that I’m here doesn’t mean that it’s going to get done any better,” Bonafilia said.

Correction: This article was updated at 11:37 am on Sept. 24 to reflect the fact that the College burns up to 1,800 dekatherms of gas per day. Previously, it was stated as 1,800 dekatherms of gas per hour.