Review: Follies musical by Stephen Sondheim ’50 is dazzling yet dark

March 2, 2022

Despite being a self-proclaimed Stephen Sondheim ’50 aficionado, I must admit that with the exception of a few songs, I did not know anything about his 1971 musical Follies. That is, until Saturday, when I watched a recording of the London National Theatre’s live 2017 production presented at the Clark Art Institute.

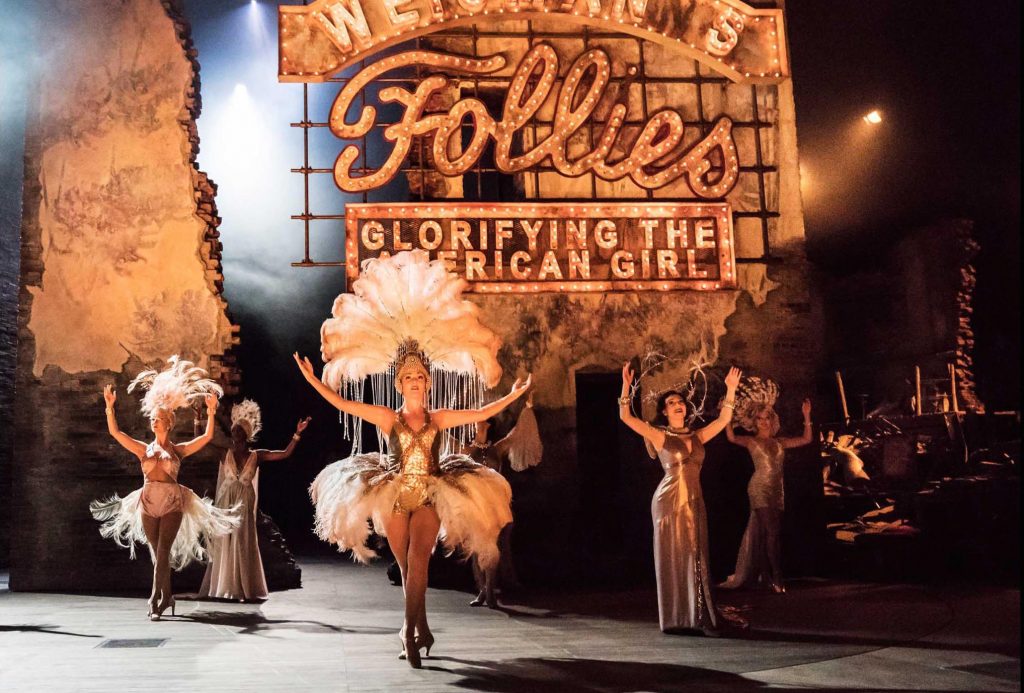

In my defense, Follies is not the type of show that many young people would know. Its main characters are all older than 50, and the themes of midlife crises and lost love are not the most appealing to younger theatre fans. Set in 1971 (the year the show first premiered on Broadway), the story follows a reunion party of the “Weismann’s Follies” (based on the Ziegfeld Follies), an elaborate musical variety show that played on Broadway between the world wars starring attractive young showgirls.

The party takes place 30 years after the Follies’ final performance at the Broadway theatre where their shows took place, which is scheduled for demolition to become an office building. As the former showgirls visit the venue one last time, they also revisit that period of their life and reckon with who they have become. Or, as Weismann (Gary Raymond) says when introducing the party, they “have a few drinks, sing a few songs, and lie about themselves.”

The main characters are two couples reconnecting at the Follies reunion who are all now deeply unhappy in their marriages. Sally (Imelda Staunton) and Phyllis (Janie Dee) were showgirls and roommates back in 1940, while their respective husbands Buddy (Peter Forbes) and Ben (Philip Quast) waited at the stagedoor each night to shower them with adoration. While the flashback scenes show the pairs deeply in love, the present day reveals that much has changed. Despite her marriage to Buddy, Sally is still in love with Ben, Phyllis’ husband, meanwhile Ben is too self-absorbed to pay any attention to Phyllis.

In addition to the age of the characters and the themes of the show, Follies is also a massive scale production, which makes it hard to put on at any school or youth community theatre. Directed by Dominic Cooke, this production features a cast of 37 actors and an orchestra of 21 musicians, creating an elaborate and absolutely brilliant production that reminded me of what I love about classic musicals. The brass section shines in songs that sound just like those of the leading 1920s and ’30s Broadway composers, a large, full sound not often heard as modern Broadway orchestras tend to downsize. The ensemble members stun in costumes and headpieces designed by Vicki Mortimer — completed with feathers and swarovski crystals — and dance with the precise stylistic movements and grace reminiscent of the showgirl era, choreographed meticulously by Bill Deamer. It’s no wonder that the show, unlike most of Sondheim’s shows, is not frequently revived or scaled down. To do it justice, it must be done in full force.

I also must note that the magnificent Dawn Hope as Stella is the only Black — or visibly non-white — actress in the show. The unmissable marquee across the stage reads “Glorifying The American Girl,” and while I don’t doubt that whiteness was the standard of the glorified American girl of the 1940s, it is now nearly a century later, and it is unacceptable to produce theatre with such a white cast when there are many talented non-white actors who could play the main characters if given the opportunity.

The script, written by James Goldman, does not have much of a main plot. Instead, it centers on characters and the emotions they uncover as they revisit this time in their life — as Sondheim does best, these deep emotions are explored through song. In addition to the four main characters, many other former Follies girls have showstopping moments of their own as the nostalgia and pain of their pasts are explored through song. While the two main couples have many amazing songs, my favorite songs belong mainly to these side characters, such as Hattie (Di Botcher) singing the classic “Broadway Baby” about life in show business and Carlotta (Tracie Bennett) singing “I’m Still Here” about survival despite setbacks and a changing world. It is these moments, more so than dialogue-based scenes, that really bring the characters to life, by showing what the showgirl life was like, and what the older women now miss.

While many songs explore themes of loneliness, the stage is rarely bare. Each character is also portrayed by a younger version of themselves, the version of them who existed the last time the characters were at the theatre. In this way, the show takes place in both the present (1971) and the past (1940). The existence of both flashback and present-day actors magnificently highlights the disconnect between past and present, by illustrating the unreachable, long gone version of themself that each character is longing to get back. The visions of their younger selves represent the rose-colored glasses through which the characters look back at the past and face the inevitability of aging.

When all the girls perform their old hit chorus line number “Who’s That Woman?” (led by the marvelous Dawn Hope as Stella), the image of the women recalling the glory days is magnified by the younger versions of each woman dancing behind and around them in the full costumed beauty that the present-day women desperately miss. The younger versions of the characters also further the power of “In Buddy’s Eyes,” a heartfelt song sung by Sally as she tries to convince Ben (and herself) that she does love her husband Buddy. As she sings, we watch young Sally and young Buddy fall in love, as well as young Sally and young Ben have an affair. In this way, the musical follows the rule of “show, not tell,” as viewers see the chemistry and drama unfold while it is sung.

The shadow-younger-self is a brilliant choice both in the book and direction. It is a flexible and dynamic decision that takes different shapes depending on the theme: sometimes ghostly, sometimes dazzling. When the characters sing, talk, and interact with each other, it’s up to audience interpretation whether they are talking to each other in the present, to the past version of the other characters, or even to the past versions of themself.

Towards the end of the show, reality fades away and both the past and present versions of the four protagonists perform vaudevillian songs and dances portraying their follies — the word is used in this sense to mean their shortcomings. The ending of this sequence, and the ending of the show itself, is quite unsettling. The four characters have a group nervous breakdown and mid-life crisis as they grapple with letting go of their pasts and moving on with their mundane futures. As the reunion ends, the theatre space is demolished along with the version of themselves that existed in the building. The women are no longer naive showgirls, they are old women who must come to terms with their age and the toxicity of their marriages.

Perhaps this is what makes Sondheim’s work so revolutionary: Through his compositions, he turns adult issues right back to the adults who come to the theatre looking for an escape. No amount of feathered headdresses and joyous tap numbers can hide the show’s underlying message. All audience members who came hoping for entertainment instead face the fact that they must let go of whatever past self they are still holding on to. They must grapple with the loss of fantasy that comes with growing up and moving on.