Behind the scenes: Friday night shows at Milham Planetarium

February 23, 2022

At 8 p.m. every Friday night, a group of students excitedly gather in a tight room as the lights dim. Instead of blaring music and dancing, the students turn to face a projector. No, it’s not a party — it’s the Milham Planetarium show.

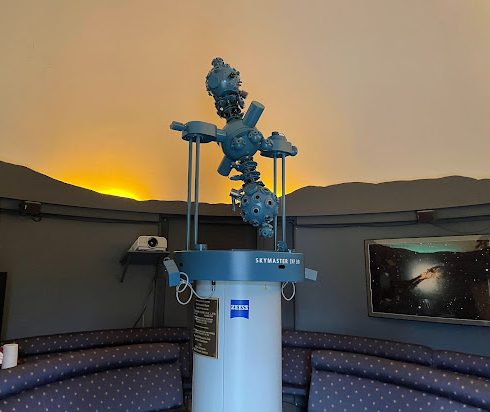

The Milham Planetarium is located in the Hopkins Observatory, the oldest extant observatory in the United States. According to the College’s astronomy department website, the space was originally used for astronomical research before transitioning into a planetarium in the 1960s, when the stars painted on its domed ceiling were replaced by high-level planetarium projectors. Since then, Milham Planetarium has been the site of regular planetarium shows, where Planetarium Teaching Assistants (TAs) take guests on an hour-long tour of the cosmos.

Dr. Kevin Flaherty, lecturer in astronomy at the College, serves as the observatory supervisor, a role that primarily involves recruiting TAs to run weekly planetarium shows. “[I meet] students in Astronomy classes who seem like they’re really excited about [the subject and] bring them on board,” he said. “As long as [they’re] interested in Astronomy, then that’s really kind of the biggest criteria.”

But outside of his role in recruitment, Flaherty said the effort is entirely student-run. This academic year, the Planetarium TAs include Tasan Smith-Gandy ’24, Michael Arena ’23, and Jadon Cooper ’22, with Peter Knowlton ’21.5 and Isaac Wilkins ’22 serving as Head TAs for the fall and spring semesters, respectively.

Wilkins, a physics and philosophy double major, admitted that he hadn’t heard much about the Milham Planetarium before becoming a TA during his sophomore year. “There was just an empty role in the Planetarium position, and I was pretty close with Dr. Flaherty at the time … so he encouraged me to come try it out, and then I just loved it,” Wilkins said.

Once recruited, the TAs were given a crash course on how to host the shows. In addition to on-campus research, Knowlton — a recent alum who majored in astrophysics — spent last summer training potential candidates. “I [took] them in, [ran] them through the process of getting the building all set up and turning on the projector,” he said.

The projector, a Zeiss Skymaster ZKP3/B, displays thousands of star clusters, galaxies, and nebulae to simulate a real night sky. The audience reclines as a TA narrates the show, choosing which parts of the sky to project through a control panel, outlining constellations, and highlighting celestial objects.

Smith-Gandy, an astrophysics and music double major, was one of Knowlton’s TAs-in-training. Though the projector’s panel of glowing controls seemed intimidating at first, he said that it only ever took TAs one try to get the hang of it. Once TAs can easily determine which part of the sky they’re in, “it ends up being self-explanatory,” Smith-Gandy said.

However, after basic technical training, TAs are given free rein. “The content of the show, I leave up to the students,” Knowlton said.

For Wilkins, this freedom was the most exciting part of working at the observatory. “[I asked myself,] ‘What parts do I find interesting? What parts are cool, but maybe don’t fit in?’” he said. “The first half [of my presentation] is mostly constellations and … how different cultures throw up their stories into the sky. And then, [in] the second half, I bring it to the astrophysics bit … [like] how, depending on the mass of the star, stars could die and become white dwarfs, or stars could fall into themselves and become neutron stars, or they could fall into themselves and become black holes.”

Arena, an astrophysics major, has a different approach. “I have no interest whatsoever in mythology or in the constellations,” he said. “Of course, I sort of pay some service to it … but I am much more interested in the physical world than sort of the stories that humans have told about it.”

Although the TAs framed their presentations differently, there was one common thread: their deep passion for science communication.

“Anyone who has been forced to exist in the same place with me for more than a few minutes will know that I have a tendency to tell all sorts of stories about [astrophysics],” Arena said. “I’m a bit of an overstuffed filing cabinet with all these stories waiting to pop out and bother people.”

Wilkins said that he particularly loves the challenge of making complicated physics topics digestible for a broad audience. “I learn best in the physics classroom when professors anthropomorphize,” he said, referring to the attribution of human behavior to nonhuman objects. “I’m so glad there are these opportunities for these difficult concepts to be made more accessible and make people excited because in my opinion, there’s nothing more exciting than physics.”

Although he was originally unsure of where to take his astrophysics studies, Smith-Gandy said that hosting the planetarium shows spurred a new interest in academia and science communication. “I love getting questions,” he said. “If anyone asks me a question about space, any time of the day, I will sit down and stop doing what I’m doing and just answer it… It very much excites me to talk about it.”

According to Wilkins, all questions are welcome during shows, especially those he can’t answer. “I did a show for some scouts back in December… The questions they [asked were] so specific, like: ‘How many stars are there?’ I was like, ‘I don’t know.’ But they’re so inquisitive and I love when people ask questions, because then it’s like we’re trying to understand together.”

The TAs are also impressed, not offended, when they are corrected. “There was this one scout who knew his stuff,” Wilkins recalled. “And I was like, ‘[T]he universe is 14 billion years old,’ [and] he’s like, ‘14.3.’ And I’m like, ‘Yep, 14.3 billion years old.’”

For Knowlton, who thinks of astronomers as “kids that didn’t grow up,” the effects of his time as a Planetarium TA loom large in his life after graduation. He now works at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz., as an educator, and said that “the planetarium definitely steered [him] towards this path right now.”

But unfortunately, no amount of passion can save the Planetarium TAs from the occasional cosmic mishap.

“It was my first show,” Wilkins said, laughing, “and it was open to non-Williams College folks. And some guy that lives in Williamstown, 20 minutes [after the show began], was like, ‘I have to go to the bathroom.’” Since the closest bathroom to the Milham Planetarium is in the neighboring residence halls, Wilkins said he had to stop the entire show, open the dorm, and awkwardly wait until the guest returned.

Smith-Gandy said that he has had to adapt to the quirks of the projector, including how “the Milky Way ends up looking ugly after a while” and the mysterious presence of the “anti-Sun,” an inaccurate disk that shows up opposite to the Sun during planetarium shows. The anti-Sun has become a running joke among Planetarium TAs. “We could [tell people] that there’s an anti-Sun, and they’d absolutely believe it,” Smith-Gandy joked. “It [is] hilarious.”

“Williams can be a very nose to the grindstone, very stressful place,” Knowlton concluded. “You [always] want to do well on your next exam or you want to do well on your problem set… So the Planetarium kind of offers a space [to remember], ‘Oh, yeah, learning is really fun.’”

The Milham Planetarium shows run every Friday night at 8 p.m. Sign up through their Daily Messages announcements every Thursday and Friday or through the Milham Planetarium website.