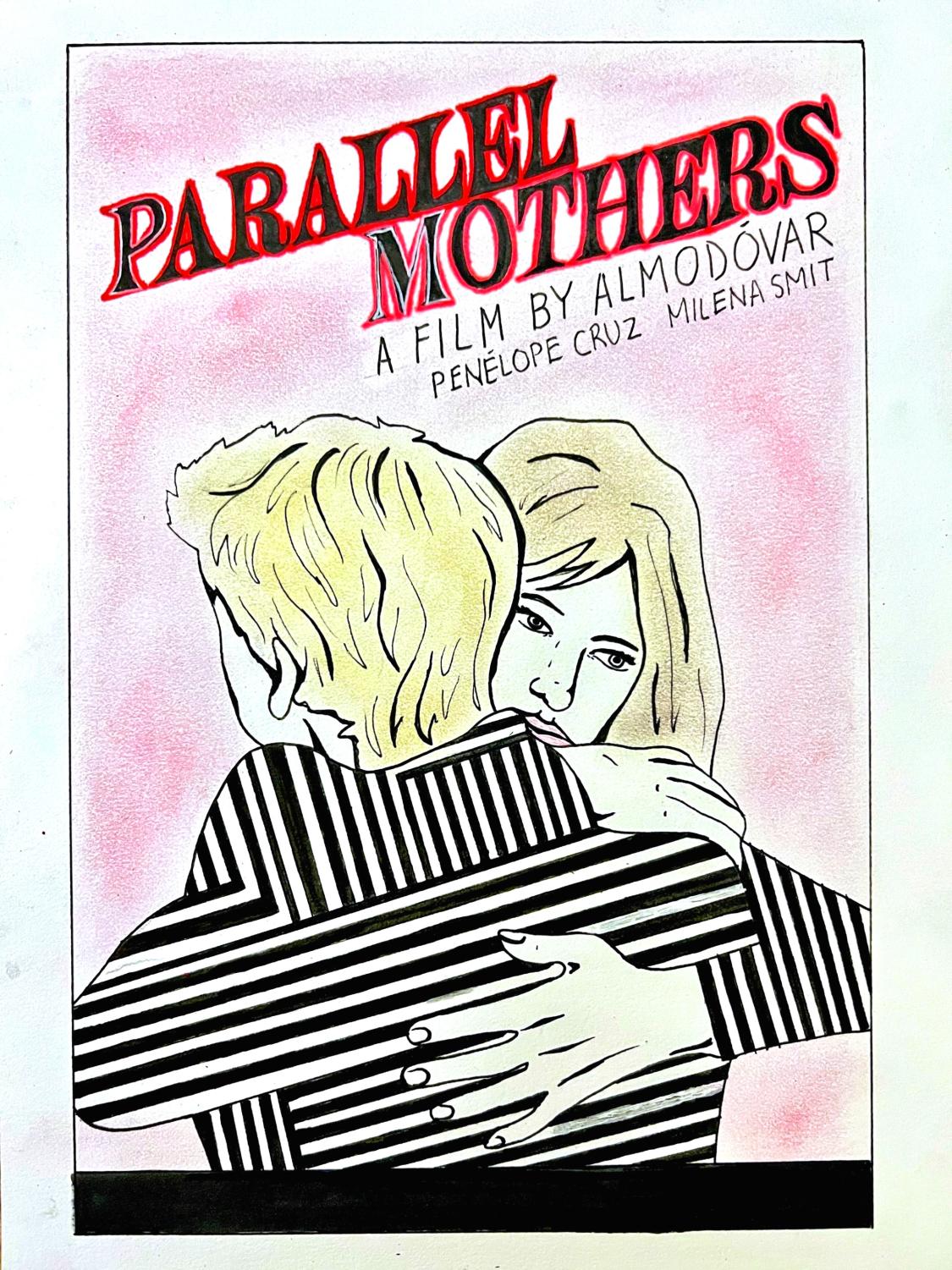

Images in Review: Parallel Mothers juxtaposes two motherhoods

February 23, 2022

A young child looks down at an excavated pit of tangled skeletons in the final scene of Parallel Mothers. The camera pauses on her face for a moment, her expression ambiguous. Is she puzzled? Sad? Afraid? The girl, Cecilia, is still too young to understand the bodies around her, but her family’s past — and indeed Spain, her country’s — is marred by death and sorrow. Parallel Mothers explores these dual personal and collective histories through the stories of two women who are forced to dig up the truths they would rather leave buried.

We learn early in the film that before Cecilia was even born, her great-great-grandfather Antonio’s remains lie among the long-forgotten skeletons. Cecilia’s mother, Janis (Penélope Cruz), tells us that Antonio was executed during the Spanish Civil War. He was a victim of the brutal fascist dictator Francisco Franco. Only in recent years have the Spanish begun to unearth the mass graves of those killed by the Franco regime to give them proper burials. Janis shares her family’s story with a forensic anthropologist named Arturo (Israel Elejalde) in the hopes that he can help excavate the bodies. The two hit it off, perhaps a little too well. After he agrees to help her, Arturo gets Janis pregnant with Cecilia.

Soon after, Arturo vanishes, as essentially all the men do in this movie (don’t worry, though; Arturo and his incredibly good looks will return at the end!). Janis is left to face motherhood alone, carrying on in the “family tradition” — as she calls it — of her own mother and grandmother.

The direction of the plot shifts with the entrance of Ana (Milena Smit), a pregnant teenager who Janis meets in the maternity ward. The two women give birth to their daughters, Cecilia and Anita, on the same day, and their relationship develops over time as Janis takes Ana into her home to work as a nanny.

The contrasts between these “parallel mothers,” Janis and Ana, are striking. Janis, who is in her 40s, sees Cecilia as both a happy accident and her last chance at motherhood. Ana, on the other hand, is ambivalent at best and feels burdened by her child. Writer and director Pedro Almodóvar, who is known for his love of blindingly bright colors, paints the screen with a palette of saturated reds, teals, and yellows to emphasize and accent the differences between his characters. In the maternity ward, for example, Almodóvar frames shots of Janis with an optimistic yellow, which suits her character just as well as the more sullen, conflicted teal behind Ana. These colors recur throughout the film, cueing us in on the characters’ inner lives.

Yet Janis and Ana share more in common than first meets the eye. Both have difficult pasts stained by tragic loss. Out of a desire to avoid confronting that loss, the two women deceive each other and themselves. I wish I could say more, but Almodóvar has built the film around the slow reveal of information. Bit by bit, we, as viewers, assemble the story. Each piece falls perfectly into place; to ruin any one would make the whole structure collapse.

Alberto Iglesias’s lush, dramatic score moves in perfect step with the film’s pace and potent images. In parts, it is richly enigmatic, its eerily oscillating strings and jagged edges recalling the music of the great film composer Bernard Herrmann. The comparison is apt, since Herrmann scored many of Alfred Hitchcock’s famous thrillers (Psycho, Vertigo), and Almodóvar’s exploration of memory and the psyche feels like a nod to Hitchcock. Iglesias’s score is full of mystery, tension, passion, and, when the credits finally roll, an overwhelming sense of relief. His music contains within its bounds the full emotional range of the film itself, and it often meshes with the performances and dialogue to breathe interior life into the characters.

This sense of interiority emerges not only from the acting or the script but also from all of the exterior things — clothes, set design, makeup — we might overlook in another film. The outfits illuminate the characters in Almodóvar’s films. Ana’s evolution from struggling teenager to self-possessed adult is reflected in her changing style. Janis is often more utilitarian in her dress. As a single mother in her 40s, her life is a careful balancing act between her devotion to Cecilia and her career as a photographer. It’s not insignificant that Cecilia works as a photographer: Her pictures, and those from the past, play their own role as exterior objects that drive plot and character. They are vehicles for truth otherwise concealed, or worse, forgotten.

The movie proves why forgetting is much easier than remembering. It’s less painful to leave the bodies of the dead buried — to pretend, as was the official Spanish policy for decades, that nothing ever happened. Yet, as Almodóvar shows through the story of Janis and Ana, forgetting is also untenable. Their relationship is analogous to and inseparable from the wider situation in Spain. The film’s mothers link these parallel histories in their struggle against the fading of memory. We understand this best when Cecilia is taken to see the grave of her great-great-grandfather, though I think it hits us even earlier: When Janis holds Cecilia up to her face after giving birth, we somehow get it implicitly. Even the image of Janis and Cecilia’s first meeting is surprisingly poignant. It’s unusual to witness such beautiful intimacy on film, and if nothing else, the scene reminds us that we should call our moms more often.

Cecilia’s birth is an important part of Janis’s personal history, just as profound as the death of her great-grandfather or the end of Franco’s regime.

Parallel Mothers reveals that moments in the past, however small or large, can speak volumes. Through its dual stories of collective and personal history, the movie brilliantly reveals this fact.

Almodóvar’s film is well worth seeing and will leave you thinking for days. The superb acting, script, and score pull it together into a work of provocative power. Before the credits roll, we are left with the words of acclaimed writer Eduardo Galeano: “No history is mute. No matter how much they own it, break it, and lie about it, human history refuses to shut its mouth.”

Parallel Mothers is now playing at Images Cinema until Feb. 24.