From Williamstown to Wembley: Mike Masters ʼ89 on his journey to the heart of English soccer

February 16, 2022

Wembley Stadium, located in London, England, is a name that carries special significance for soccer fans around the globe. Referred to by the legendary soccer player Pelé as the “cathedral of football,” the 90,000-capacity stadium serves as a focal point for the British national consciousness and has been the backdrop for some of the game’s greatest moments since its construction in 1923. Although Wembley has hosted events ranging from major concerts to parts of the 2012 Summer Olympics, the stadium’s primary purpose has always been for soccer, and few athletic stadiums come close to its level of global recognition and mystique.

To this day, only three Americans have ever scored a goal at Wembley. The latest is Christian Pulisic, the current face of American soccer who is widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest talents the United States has ever produced. Before him was John Harkes, a member of the U.S. Soccer Hall of Fame, the first American to ever score in the English Premier League, and a color commentator for ESPN after a long and illustrious playing career. But the first? That would be Mike Masters ʼ89 — a name much less familiar to American soccer fans. This is his story.

Masters came to the College in the fall of 1985 from Long Island, N.Y. Recruited to play both soccer and basketball, Masters ended up captaining both teams over his four years at the College. “I was primarily a basketball recruit,” Masters said. “[But] soccer was probably my number one sport.”

At the College, Masters majored in economics and shone on the soccer field, earning first-team All-American honors his junior and senior years. In spite of this, Masters said that pursuing a professional soccer career was not on his radar for most of his collegiate experience. “Soccer was something I loved and enjoyed, but there wasn’t really a [professional] league at the time,” he said.

By the fall of his senior year, however, a professional American soccer league had been established, with a team even playing in Albany less than an hour away. After being scouted by their coach, Masters signed a contract with the Albany Capitals while still enrolled at the College, attending classes on the weekdays and playing games on the weekends. “That was really a spring [and] summer league,” Masters said. “My senior spring, I would drive over to Albany at least once during the week, and then we would play our games on the weekends, so I was driving back and forth.”

Masters continued to play for the Capitals after graduation. “It wasn’t a lot of money, but it was a way for me to continue playing and maybe postpone getting a real job,” he joked. While the league was fully professional, it was newly established and lacked funding, meaning that many of the players, including Masters himself, had to take on other jobs to make ends meet during the offseason. “That first year after we wrapped up [the season] in Albany, I came back to Williamstown and was the Mount Greylock [Regional School] soccer coach, the Williams JV basketball coach, and a substitute teacher,” Masters said.

After his second full season, Masters was able to leverage a connection with a teammate from the Capitals who had played for the English national team to get an opportunity abroad. “He invited me over to England and introduced me to his [former] club … Ipswich Town,” Masters said. Though he tried out for Ipswich Town and impressed the coaching staff, he could not get a work permit; thus, he could not join the team.

However, Masters soon after had another chance to play in England: Colchester United, located in the borough of Colchester around 20 miles away from Ipswich, expressed an interest in him. Having just been relegated from the Football League, the top four divisions of professional soccer in England, Colchester was down on its luck and languishing in the fifth tier of English soccer. In stepped Masters, just a couple years out from his time at Williams.

Playing for Colchester was a completely different experience for Masters. “[Soccer] just gets so much more attention,” he said. “In the U.S., we were all in part responsible for promoting the team and the league. In England, it’s the number one sport, so you may be playing at a lower level, but in Colchester everyone would go to the games and you’d have a following… It was a more established league.”

Masters also found himself surrounded by teammates with very different experiences than what he was used to. Many of his teammates had left school before 18 and committed to a professional soccer career at an early age. “They were working class, this was their job, this was how they made their living, and so it was much more serious,” Masters said. “With Albany, I think almost everyone I played with had a college degree. [For them], there was always another path … whereas in England, it was different — soccer was their way to a better life, and that’s what made it way more intense.”

“There was certainly a ‘Who [does this] this Yank think he is, coming and playing our sport’ [type of] arrogance,” Masters added. “So there was a time I needed to prove myself, and that’s true of any player, frankly.”

Even in the fifth division, Masters described his games as a “higher standard of play” compared to his experience in the United States. With this increased level of competition and public attention came a greater level of responsibility. “If I’d go out for something to eat or to the dry-cleaners, everyone kind of knew who [I was], which is good and bad,” Masters said. “When you’re winning, it’s good, and when you’re losing, they’re not shy about telling you.”

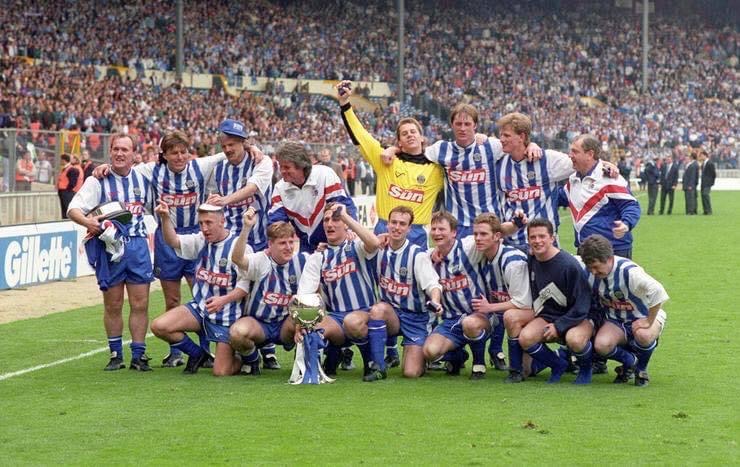

Fortunately for Masters, his time at Colchester was largely successful. In his second season with the club, Colchester won the fifth division title and achieved promotion back to the Football League, with Masters playing a key role. In the Football Association Challenge (FA) Trophy, a tournament for clubs outside of the Football League, Colchester reached the final — meaning that Masters would be playing at Wembley, uncharted territory for all but a few American soccer players.

“At the time, I didn’t really appreciate what playing at Wembley meant for my teammates and the fans,” Masters said. “It was more important for the club to actually win the [fifth division] and get promoted than to play at Wembley, at least I thought so.” But the sheer amount of support Colchester received on the day of the final was something that stuck with Masters. “We were [usually] getting 7000, 7500 people to the games, and that was kind of capacity,” he said. “For the game at Wembley, Colchester sold [around] 35,000 tickets. You had all these people come out wanting a day out at Wembley, because it’s not often clubs get to play there.”

In spite of the intense atmosphere, Masters said that he was able to control his nerves during the final. “I don’t remember feeling a lot of pressure — I felt like I was in pretty good form and we had a good unit,” he said. “Once the game starts, that’s where your focus is… The pressure was [more apparent in] all those league games, because we knew we couldn’t lose a single game or we wouldn’t win the [division].”

Masters scored the first goal of the game, making him the first American to ever score at Wembley. Colchester ended up winning the final 3-1. While that milestone has since been matched by Harkes and Pulisic, Masters insisted that their achievements have different contexts. “I was playing in the FA Trophy [final], John Harkes was playing in the League Cup and FA Cup [finals] — much, much bigger games,” he said. “It’s nice to be mentioned in that company, but both of them have reached levels well beyond what I did.”

While Masters left Colchester to return to the United States after the 1992 season, he continued to play professionally for several years. A particularly memorable moment came just over a month after the FA Trophy victory, when Masters was called up to the United States national team to play against Ukraine at Rutgers University. “Because I grew up in Long Island, Rutgers is not far from home, and it was easy for friends and family to show up, and that was great,” he said. “I think that’s what every soccer player wants: to play for their national team.”

In his final years of playing professional soccer, Masters took up a coaching position at DePaul University in the offseason while studying for an MBA. Upon graduation, he took a job in banking, where he has worked ever since. “When I retired, my last game was emotional,” Masters said. “But for me, it was time to move on to different things.”

The 1992 season was not the last time Masters would live in England, however. From 2013 to 2018, Masters relocated to London for work, this time for banking instead of soccer. “It was great — I still had friends over there from my playing days,” Masters said.

Over twenty years later, his playing career for Colchester was still brought up. “I didn’t go around advertising my history with soccer, but some people inevitably found out about it,” Masters said. “One time, [I met] a CFO of a company from Colchester, and he said he remembered going to the game at Wembley … that was pretty cool.”

Masters is currently back in the United States, but Colchester United and the team that won at Wembley still holds a special significance for him. “I think I’m going to go over in May because it’s the 30th anniversary of that 1992 team,” Masters said. “The town of Colchester is hosting a dinner [for the team], so I’m going to try and make it back for that.”