Review: Cie Hervé Koubi performs What the Day Owes to the Night

February 16, 2022

On Feb. 10, in collaboration with the ’62 Center for Theatre and Dance, the Cie Hervé Koubi dance company streamed their performance What the Day Owes to the Night over Zoom. The performance concluded with a question and answer segment led by Associate Professor of Africana Studies Rashida K. Braggs, and included choreographers Hervé Koubi and Guillaume Gabriel, as well as company dancer Houssni Mijem.

The Cie Hervé Koubi dance company, founded in 2001, is primarily composed of dancers of North African descent. For the 2009 casting of this particular performance, there was no specific dance technique requested. Most of the dancers in the 2022 production learned to dance in the streets, without formal dance training. Koubi flawlessly incorporated their many distinctive styles — hip-hop, contemporary, and even Sufi dance — into the explosive yet delicate movements of the piece.

The performance opened with a mass of bodies rolling on the floor, illuminated by dim overhead lights. A gong rang out while they gradually moved to their feet. Slowly, the standing dancers transitioned into a synchronized, undulating movement. As their motions became more energized and frenzied, the drums and electric humming in the background evolved into a violin concerto. Soon the dance reached its peak; the dancers flipped, spun, and jumped across the stage.

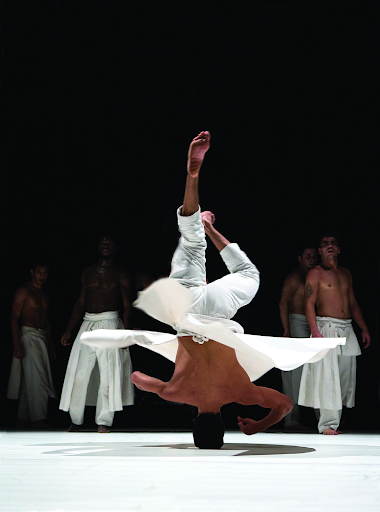

Often, in impressive feats of strength, the performers spun on their hands in handstands, and some even spun on their heads. At times, they would run at each other to be caught in another dancer’s arms. Partner work, in which two or more dancers used each other’s bodies and weight to move around the stage and into the air, was central to this piece.

While the dancers’ bare upper bodies and visible muscles displayed their strength, their movements and loose clothes contrasted with some softness. The performance was reminiscent of Sufi whirling dervishes, members of a Muslim religious group who have taken vows of poverty. Sufi whirling is a form of religious meditation in which the dervishes turn in long white skirts. The dancers’ loose white pants and skirts reflected the dervishes’ clothing, and their spinning movements furthered the resemblance.

The choreographer and founder, Hervé Koubi, was inspired by his Algerian roots. His family moved to France at the end of the French-Algerian war, but didn’t tell him of their Algerian descent until he was 25. In the Q&A section of the show, Koubi explained that the dance is symbolic of his mixed background. He spoke about the Mediterranean basin and how the two sides of the sea — Algeria and France — are culturally and geographically linked. When asked about the piece’s message, Koubi said it was about a sense of belonging that is stronger than nations and borders. What the Day Owes to the Night is a biographical piece, one of identity and belonging.

These themes are evident throughout the performance, as the dancers repeatedly used each other’s body weight to resist gravity, holding on to each other and leaning away. In the most memorable moments of the dance, some of the men gathered together to throw fellow dancers high into the air, a feat that required trust in fellow dancers and reinforced the piece’s sense of community.

Houssni Mijem, the company dancer who participated in the Q&A, noted Koubi’s signature “calligraphic movement” when working with individual dancers. Koubi often asks his company members to dance as if their bodies are painting calligraphy, each movement connecting to the next. Though they maintain the same flow, even when all the dancers are doing the same choreography, they can each have their own individual take on the movement.

What the Day Owes to the Night was a breathtaking display of both strength and delicacy in movement. The overhead shots and camera angles perhaps even enhanced the viewing, as audience members got a clearer view of choreographed formations from above. Although some technological glitches may have reminded us of the advantage of in-person viewing, it is a testament to the choreography and the dancers that the work could still communicate such a powerful message and captivate an audience virtually.