Milk Tea Alliance, students, administrators navigate the aftermath of the Jan. 4 tabling incident

February 9, 2022

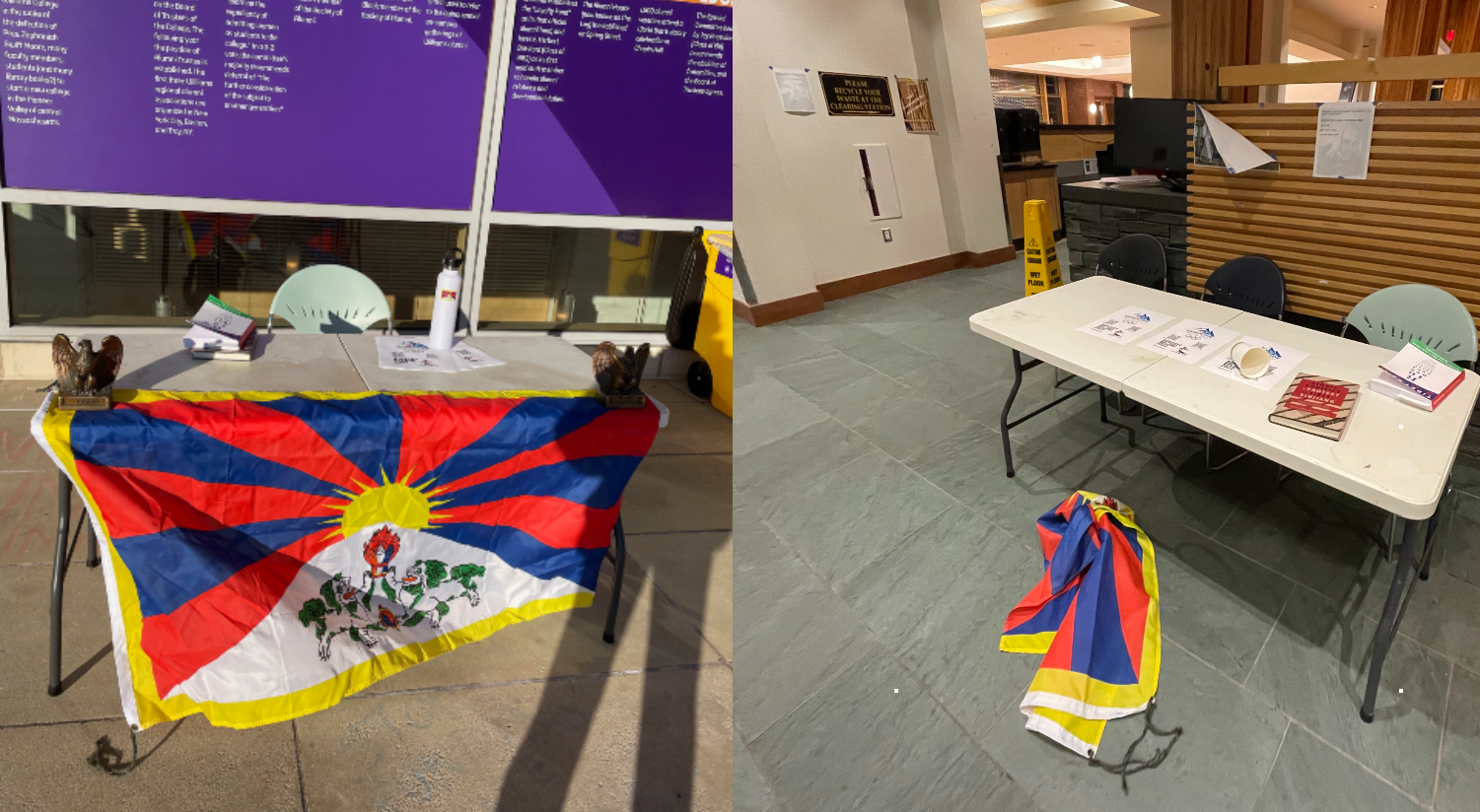

On Jan. 4, Topjor Tsultrim ’22 returned from a dinner break to the table he had set up at Paresky to speak to passing students about the Milk Tea Alliance to find his Tibetan flag lying on the floor. The two bookends shaped like eagles — a gift from his father — that had been anchoring the flag to the table were missing.

“I immediately took pictures of everything,” Tsultrim said. “I was intimately aware of the kind of hatred that was without any doubt behind that action. It’s a hatred I’ve seen take many forms in my lifetime, my parents’ lifetime, my grandparents’ lifetime… To see it manifest quite literally in the heart of this Williams College campus, the place that I have grown to call home for the past four years, was stunning, was chilling, was fundamentally unnerving.”

Over the course of the next month, Tsultrim reached out to multiple institutions on campus — including Campus Safety Services (CSS), the Davis Center (DC), and the Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (OIDEI) — in search of an investigation into the perceived bias elements of the incident, as well as support for the Alliance’s goals on campus. According to Tsultrim, only some of these efforts proved successful.

Much of the administrative outreach to Tsultrim was geared towards helping the Alliance spread its message. Director of the Davis Center Dr. Eden-Renée Hayes wrote in an email to the Record that the Davis Center hopes to collaborate with the Alliance in hosting a “listening circle or facilitated dialogue around repairing harm and developing understanding with [Assistant Vice President for Campus Engagement] Bilal Ansari” and support the planning and funding of the Alliance’s future events.

“Topjor was looking for an administrative response and the support I offered is part of that administrative response,” Hayes wrote.

However, for Tsultrim, this administrative response ultimately fell short of what he said that he and the Alliance had hoped for. “What we needed in that moment, which was [the Davis Center’s] support in having taken this [incident] seriously in front of the administration, their support in calling a spade a spade, and adding their institutional voice behind our efforts — we were not able to find that,” he said. “And I find that sickening.”

The Milk Tea Alliance: ‘A cross-identity approach to activism’

Late last fall, Tsultrim co-founded The Milk Tea Alliance — inspired by the global coalition movement of the same name originally begun by pro-democracy and pro-freedom activists in Hong Kong and Taiwan — on campus in an effort to educate the College community about human rights violations committed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) within its “claimed” territories and beyond.

“[The Alliance] is a group that wants to shed light on issues that are not only dear to my heart and to Topjor’s heart but, on a larger scale, [to] just educate and keep up the awareness on this campus about transnational issues that don’t have immediate consequences on the U.S. population, maybe, at least currently,” Wilson Lam ’22, one of the Alliance’s other founding members, said of the organization’s objectives.

The organization derives its name from the shared cultural practice of adding milk to tea prevalent across Asia, emphasizing its cross-identity approach to activism. “Hong Kong, Taiwan, Malaysia, Pakistan, India, Tibet, Inner Mongolia, East Turkestan — they’re all united under this idea of naming and resisting the ongoing encroachment of the Chinese Communist Party’s influence around the world,” Tsultrim said.

Following an inaugural interest meeting in early November, the organization’s first major campaign in the new year was to forward a diplomatic boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, China, to raise attention about human rights violations by the CCP against Uyghur Muslims, which has been labeled as genocide by the U.S. government.

“[Instead] of a total boycott, [the Alliance] has called for a diplomatic boycott from various national governments, which the U.S. has elected to [do] on the grounds of gross human rights violations … so no government officials and no dignitaries will be sent, signaling that this is not business as normal,” Tsultrim said.

Ben Floyd ’25, a student from Maryland, told the Record that he became a member of the Alliance after a chance encounter with its founders and felt the need to take a “deeper look” at China’s growing global presence. “I think it’s always important to speak truth to power,” Floyd said. “And while I believe it might be a little bit hypocritical to challenge China for their wrongdoings when obviously my own country has done so many terrible things, I don’t think that excuses them at all.”

Around the world, activists marked the one-month countdown to the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics with a global day of action on Jan. 4; the Alliance participated in this day of action by tabling outside Paresky Center and Driscoll Dining Hall, passing out flyers detailing its call for a diplomatic boycott and engaging students in conversation. The incident involving Tsultrim’s missing bookends and the Tibetan flag occurred later that evening.

Jan. 4 incident

With the help of several members of dining hall staff, Tsultrim combed through trash cans across Paresky, searching for the missing bookends, but was unable to locate them. When he called Campus Safety Services (CSS) to report the incident, they told him over the phone that the only course of action he could take was to file a lost items report, according to Tsultrim.

When no officers arrived on scene, Tsultrim walked to Hopkins Hall, where he provided a full verbal account of the incident to the CSS officer on duty. He told the Record that he explicitly stated his belief that the incident contained elements of discrimination based on his ethnicity and asked whether there were any further steps he could take for recourse. According to Tsultrim, the officer again directed him to file a general incident report, after which he returned to his dorm, recounted the entire incident in written form, and then submitted the report.

Despite repeating his request for information about resources that could help him pursue justice for the bias elements of the incident, Tsultrim claimed that CSS did not at any point inform him about the bias incident report available to students who believe they have been targetted for their identity on campus. In response to the general incident report Tsultrim submitted, CSS began an investigation only into the theft of the two eagle bookends, according to Director of CSS Eric Sullivan. As of Feb. 7, a perpetrator had not been identified, Sullivan told the Record.

It was not until several students directly reached out to Tsultrim that he learned of a different potential avenue for pursuing the bias elements of the incident: the Davis Center. “I’d also heard from perhaps an equally if not louder chorus of voices of friends I trust dearly who gave me warnings that perhaps I might not find the types of support that I was seeking from the Davis Center based on their own personal experiences with the DC that had left poor tastes in their mouths,” he said. “But nevertheless, I did not heed their calls for concern.”

College Response: ‘A chance of being taken seriously’

Tsultrim said that when he scheduled a meeting with Hayes on Jan. 6, he had two goals in mind. “First and foremost was the idea of talking to them about this being a hate crime that occurred on our campus and wanting the response from the College to be commensurate with the tragedy that had unfolded,” he said. “And my other ask [for] the DC was to help demystify the ether into which I had cast my incident report because I had had no follow-up from CSS.”

Neither of his goals was ultimately met, according to Tsultrim.

During his first meeting with Hayes, “she was effusive in her offers of support,” Tsultrim said, noting that she offered to provide the Alliance with Minority Coalition (MinCo) funds to secure speakers, even though the Alliance is not a MinCo-affiliated student organization. According to Tsultrim, when he directly asked her for affirmation that the incident was a hate crime, she readily gave it.

“Immediately, I was met with, ‘Oh, yes, for sure. This is a hate crime,’” he said. “And it’s difficult to be overjoyed when something’s declared a hate crime, but I was very satisfied with that response. For the first time that week, I had finally felt seen and affirmed that this had a chance of being taken seriously.”

“I had heard a chorus of voices around this campus, specifically online, essentially telling me, ‘Oh, suck it up. It’s not a real hate crime. That’s so stupid. Grow up, that’s nothing, there’s nothing there,’” Tsultrim continued. “For the first time, I had felt that I was being seen, that officials, adults at this college would take me seriously and treat [the incident] with the severity that it deserved.”

In an email sent on Jan. 6 following their meeting, Tsultrim sent Hayes the original version of a flyer he had created describing the incident as an “anti-Tibetan hate crime.” This version did not include any mention of the Davis Center, and according to Tsultrim, Hayes offered to include the flyer in the Davis Center newsletter during the meeting. In an ensuing email, Hayes thanked Tsultrim for sending the flyer and agreed to also include a line of text about support for the Alliance in the newsletter. The flyer never appeared in the newsletter.

Later that night, Tsultrim amended the posters to reflect the institutional response he believed he had received from the Davis Center. The revised flyers now included the line, “The Davis Center has positively affirmed this [incident] as a hate crime, but the administration has made no public comment.”

Around 5 a.m. on Jan. 8, Tsultrim and a few other students plastered the amended flyers on walls, doors, and bulletin boards across campus. On Jan. 10, he received an email from Hayes noting the addition to the flyers and asking to schedule a meeting.

According to Tsultrim, during this second meeting, Hayes “instructed” him to take down all the flyers because she said the Davis Center is not a legal body and thus has no authority to declare an incident a hate crime. When he questioned why she had used such phrasing in his first meeting with her, he said that she “derailed” the conversation.

“She denied my recollection of the events,” Tsultrim said. “It got to the point where I told her, ‘This is absolutely incredible. I want nothing to do with the Davis Center. Please, I do not seek any of your support.’”

“Every time I pressed her on, she never ever personally denied that she did not say those words,” he added. “Every time I asked her to be clear, she would only reply with, ‘The Davis Center could not have made such a determination.’”

In a Jan. 23 email to the Record, Hayes clarified her statement to Tsultrim. “There’s a pretty specific definition of hate crime, so it is likely that there would need to be some investigation that leads to the conclusion that a hate crime has been committed,” she wrote.

In response to a written account of the dialogue from Tsultrim’s perspective, Hayes told the Record that this account was “not entirely accurate.” She did not respond to a request for further elaboration in time for publication.

Process: ‘The Davis Center cannot positively affirm anything related to a crime’

For students like Tsultrim, the steps of an investigation into a bias incident are often unclear. In a Feb. 7 email to the Record, Hayes pointed to the bias incident report on the OIDEI website as a “good place to start.” Once submitted, the form is directed to the OIDEI, but from there, the trajectory of the process becomes less clear to the individual who filed the report.

In dealing with such cases, there is a critical distinction to make between a bias incident and a hate crime. According to the description accompanying the bias incident report, a bias incident occurs when there is “discrimination against any person on the basis of race, sex, ethnicity or national origin, religion, age, disability, marital status, sexual orientation, gender identity, or veteran status.”

“When someone reports a bias incident to OIDEI or alleges they’ve been discriminated against, at the individual’s request, we will look into the matter and try to address it,” Vice President for Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Leticia S. E. Haynes ’99 wrote in an email to the Record. “In the course of looking into a matter, we leverage partners across campus — for example, we may be in contact with Campus Safety and/or the Dean of the College’s office to support our inquiry; and, if possible, we will speak with other individuals who have been identified as having pertinent information.”

A hate crime, on the other hand, is a legal term that is defined by Massachusetts state law as “any criminal act coupled with overt actions motivated by bigotry and bias.” Even though a criminal act may have actually occurred in this case — the missing eagle bookends that CSS is currently investigating as theft — administrative bodies on campus do not have the legal authority to declare an incident a hate crime.

“The Davis Center cannot positively affirm anything related to a crime,” Hayes wrote in a Feb. 7 email to the Record. “That’s not a function we can provide ourselves but we can discuss on and off campus resources, which I did when talking to Topjor.”

In the case of a bias incident, the College’s investigation is initiated by OIDEI. However, the determination of a bias incident, unlike a hate crime, does not necessarily require an investigation. “In my opinion, a bias incident does not have to be investigated and determined by OIDEI before it can be called a bias incident,” Ansari wrote in an email to the Record.

In any such investigation, other bodies on campus may subsequently become involved. “If there’s a report of an alleged bias incident that warrants investigation by CSS, then CSS is involved,” Sullivan wrote. “CSS does not automatically receive reports from the bias incident form but are contacted when necessary and involved as [is] appropriate.”

Regardless of the terminology used to describe an incident where a member of the College community feels targetted or victimized, members of OIDEI and CSS expressed their wish to provide support to those who are affected. “I don’t need to know if it is a bias incident, bullying, bigotry, hate, Islamophobia, or racism before I am motivated by love to help offer students a restorative way to heal from all harm caused,” Ansari wrote.

Investigation: ‘At almost no turn along the way have we felt any sort of outside support’

Tsultrim said his correspondence with the Davis Center left him and other members of the Alliance with “compounding trauma” and an unpromising future with the Davis Center. “After [Jan. 4] and [the conversation with Hayes] happened, the work has exclusively fallen upon the afflicted parties in our search for justice,” he said. “And at almost no turn along the way have we felt any sort of outside support.”

Though Tsultrim never submitted a formal bias incident report, he said that he was finally able to schedule a meeting with Haynes and Assistant Vice President for Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Toya Camacho through the help of Assistant Dean for Senior Year Students and Williams Firsts Janice Williams and Dean of Williams Firsts Rebecca Garcia. Having worked closely with Williams and Garcia as a member of the Williams Firsts Student Board, Tsultrim told the Record that he had confided in the two deans about the Jan. 4 incident.

“When a student believes they have been a target as a function of their identity, we recommend they connect immediately with the … OIDEI and in some instances with both OIDEI and Campus Safety Services,” Garcia and Williams wrote in an email to the Record. “We are saddened by this incident and the impact it has had on Topjor and his peers.”

According to Ansari, OIDEI had learned of the Jan. 4 incident by Jan. 7 and first met with Tsultrim on Jan. 24, where he and OIDEI extended an offer to support “[Tsultrim] and the Alliance in their efforts to spread education and heal this campus.” Tsultrim has since expressed interest in hosting a forum based on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Four Principles of Social Justice with Ansari present.

While Tsultrim said he believes OIDEI is not currently investigating the bias elements of the incident, in a Feb. 8 email to the Record, he expressed being “really happy with how OIDEI is supporting us right now.”

Student Responses: ‘At this point, I expect the College to always do nothing’

The Jan. 4 incident and Tsultrim’s flyers drew wider campus attention to the Alliance itself, igniting student debate about its calls for a boycott of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, as well as the nature of the Jan. 4 incident.

“The Olympics is this global international thing that goes beyond just showcasing athletics, like, there’s so much more politics attached to it,” Rachel Jiang ’23 said. “So I think it’s very valid to be boycotting something [in] a country where intense human rights abuses are [happening].”

Jiang, who grew up in mainland China before moving to the United States, said that personally witnessing inequalities was what drew her to the Alliance’s messaging. “I went to Tibet the summer of my senior year of high school, and I visited Lhasa, the capital,” she said. “I also taught in Yunnan, which is a southwestern province in China with a lot of ethnic minorities, [but] not particularly Uyghurs. That’s where I also saw a lot of inequalities and how these ethnic minorities were being treated unfairly by not just the government but [also] the Han Chinese majority, which is what I am.”

Micaela Foreman ’23, a student from Illinois who first learned about the Alliance by reading the flyers posted around campus by members following the Jan. 4 incident, expressed more skepticism about the rationale behind certain causes espoused by the Alliance, such as the boycott of the Beijing Olympics. “I also think that when we hear Western media calling out genocides, we should think about all the genocides they are not talking about and why that’s not happening,” she said.

“I understand that there are embodied experiences that I cannot challenge. But I will say, as someone who is very distrustful of the media that I receive, I’m wary to trust anything the United States says,” she added.

Meanwhile, the nature of the Jan. 4 incident has also been understood differently by various students.

For Tsultrim, the character of the incident was “very plain.” “What happened was, without a doubt, a hate crime,” he said.

However, others noted the importance of the relationship between how violent an act is and its qualification as a hate crime. “I feel like that language [of hate crime] — I don’t really like it,” Foreman said. “Because I think it puts [the incident] in conversation with other things that are honestly much more severe. I do think [the Jan. 4 incident] is racially motivated in that faith, and it would be some sort of injustice, but a hate crime? I don’t know if that’s the right language.”

Others, like Floyd, who participated in handing out Alliance flyers outside Driscoll on Jan. 4, voiced hesitance in ascertaining the motivation of the currently unidentified perpetrators. “I don’t really want to speculate on what I think the person that did that might have been motivated by, but if someone was doing that on purpose, it’s probably out of…disagreeing with the club in a not very civil way,” he said.

For many members of the international community, including some hailing from countries directly or indirectly affected by the CCP’s activities, the College’s lack of a public-facing response to the Jan. 4 incident was indicative of a larger trend of prioritizing domestic issues over international ones that directly affect members of the community.

While Lam, an international senior from Hong Kong, was not surprised by what he described as the College’s lack of a general institutional response to the Jan. 4 incident, he said he was “taken aback” by Tsultrim’s account of his interaction with the Davis Center. “The way that Topjor was treated by the admin — I couldn’t say I was surprised,” Lam said. “Whenever we’re upset or stuff like that, [the College] has never had positive engagement. But the thing with Topjor is the first time that I’ve seen someone be actively discouraged. Like, the Davis Center actively told him to take down the flyers.”

Daniel Kam ’23, an international student from Malaysia who joined the Alliance’s Telegram group chat, in which members of the Alliance have engaged in discussions about the College’s response to Jan. 4, shared Lam’s sentiments. “[Hayes’s] response is pretty disappointing, and it wasn’t in a very collaborative means of, ‘Hey, can we work on the posters again, and I’ll help you redistribute it?’” he said.

Jiang questioned the College’s sincerity when it does respond to incidents like Jan. 4. “[The administration] love[s] to pretend like they want to support because ultimately, the admin wants to preserve this PC [politically correct] atmosphere of ‘We are so inclusive, everyone gets along, internationals love us,’” Jiang said. “But as soon as you want to start something, [it’s] like, ‘Don’t.’ I think [the admin] wants to control the noise, and I feel like that’s what’s happening with the DC.”

Some advocated for the College to adopt a firmer stance, not just on discriminatory incidents that occur on campus, but also on international issues. “I haven’t been expecting the school to issue statements like ‘We stand against the occupation of Palestine’ or ‘We stand against the systematic abuse of human rights by China of its various minorities,’” Lam said. “But the fact that schools haven’t been making those stands doesn’t mean they shouldn’t. So I do wonder what it comes to when they enter this decision-making process of, ‘Oh, we need to make a statement on this.’”

“I feel like Topjor getting basically attacked for his beliefs … kind of ranks up there with those incidents, like when a few years back, a student found a swastika drawn on their door. I’m pretty sure there was a campus-wide email about that,” Lam continued. “So I wonder what was different about the swastika situation and Topjor’s to make the school think, ‘This is not a situation where we need to make a clear stance.’”

According to Kam, it is also important to consider the feasibility of having the administration keep track of global tragedies. “I don’t think it’s sustainable for the College to constantly have their finger on the pulse for every single issue,” Kam said.

Instead, he recommended more active involvement of the student leadership behind MinCo and its constituent student groups in the response to incidents like the one on Jan. 4. “I don’t know if MinCo representatives have discussed this issue at all, but I know that after major domestic hate crimes, there was active discussion by MinCo groups recognizing that there is a problem,” he said, “and especially when [this incident happened] on campus, I feel like MinCo groups, but specifically student bodies, could be more involved in [the response].”

“I think when student bodies, or student activists in this case, are actively trying to seek support… [the College] should have better channels and institutions that are already in place rather than students having to always self-organize,” Kam continued.

For Angus Li ’25, an international first-year from Hong Kong, the Alliance was not just a grassroots movement but also a much-needed break from the College’s distance from global politics. “Because we’re such a small and isolated community, it is really important that we have groups like [the Alliance] to remind us of what’s going on outside the Purple Bubble,” he said.

Li, like Lam and Jiang, connected the College’s lack of response to a difference in the College’s attitude towards international causes as compared to domestic ones. “I have thought about how this probably would have been handled differently if it was a ‘domestic issue’ — in the sense that you would actually get a public-facing response from the administration,” he said.

While there is disagreement over the incident’s qualification as a hate crime — and no legal affirmation that it is one — several students have agreed that the College should publicly address the Jan. 4 incident. “I think [the Jan. 4 incident is] something that definitely deserves an institutionally supported platform,” Foreman said.

Nonetheless, some Alliance members saw a silver lining in the aftermath of the Jan. 4 incident. “It’s almost like this event was a blessing in disguise because now, the spotlight is on us,” Lam said. “Now we’re being given platforms beyond the one we’ve been trying to make for ourselves on this campus.”

Editor’s Note: An abbreviated version of this article was published in the Feb. 9 print issue of the Record.