Astronomy professor, students view eclipse over Antarctica

January 26, 2022

In the early morning of Dec. 4, 2021, Chair and Professor of Astronomy Jay Pasachoff, along with students Peter Knowlton ’21.5 and Anna Tosolini ’23, flew over Antarctica in a chartered Boeing 787. For just under two tense minutes, they took photos out of the plane windows with borrowed Nikon cameras from the College library, capturing a total solar eclipse.

Scientists have observed solar eclipses for years because they present a unique opportunity to study the solar corona, the outermost part of the sun’s atmosphere. Pasachoff, a renowned American astronomer, saw his first total solar eclipse in the summer of 1959 and began taking Williams students on expeditions in the summer of 1972. Now he holds the world record of most eclipses ever seen by a human (tied with two others) — his trip in December marked his 74th sighting. He continues to travel to view eclipses for the scientific value that every one presents, Pasachoff said. “Each [eclipse] takes place at a different configuration of the sunspot cycle, so the magnetic field interacts with the corona in different ways each time,” he said.

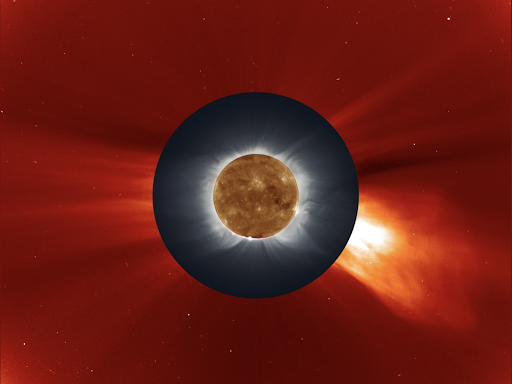

The primary goal of Pasachoff’s team was to capture an image of the eclipse and compare it to a predicted image developed by Predictive Sciences Inc., an organization that models the sun’s corona, prior to their trip. The two students were invited after taking various astronomy classes with Pasachoff. “We’re getting better and better at predicting what the solar corona will look like,” Knowlton said. “That lets us know how good our solar weather models will be.”

Solar weather includes phenomena like coronal mass ejections, a solar eruption that can cause significant destruction to satellites in orbit and power grids on Earth. “Even if we have a few extra minutes of notice, by monitoring what’s going on and understanding the configuration of the sun, we can head off a lot of potential damage,” Pasachoff said.

Beyond refining scientists’ predictions of extreme solar events, solar eclipses present a chance for researchers to further interrogate the coronal heating problem, the scientific mystery of why the outer reaches of the sun’s atmosphere are hotter than its surface. “Because solar eclipses give us the best opportunity to study the solar corona … a lot of solar physicists will flock around total eclipses to capture data,” Knowlton said.

Pasachoff’s trip to Antarctica marked his first sighting of a total solar eclipse since the beginning of the pandemic. (He did see an annular eclipse on June 10, 2021, but these events are less scientifically significant because the sun is only partially concealed by the moon, he said.) On Dec. 14, 2020, there was an eclipse over southern parts of South America, but he was unable to travel because of the College’s travel restrictions at the time. “It was the first total eclipse I missed since the 1970s. So I was pretty upset about that,” Pasachoff said. As soon as seats became available on a charter plane above Antarctica to see the eclipse, Pasachoff didn’t hesitate. “I was first to sign up,” he said.

Knowlton was also supposed to see the eclipse with Pasachoff in December 2020, the winter of his senior year. He couldn’t travel to South America, but because of the pandemic, Knowlton decided to take the spring semester off, instead returning in the fall of 2021 when he was given another opportunity to attend one of Pasachoff’s eclipse expeditions. “It was just a fortunate series of events that allowed me to be able to go on this trip,” Knowlton said.

To prepare for the brief moments of eclipse totality, Knowlton and Tosolini spent the fall semester practicing. Their camera work was complicated by the fact that they viewed the eclipse through a plane window. “What’s nice with ground eclipses is [that] you just click a button which will do all the work, and then you just get to look at the eclipse for yourself,” Knowlton said. “Because we had to worry about the plane moving around a lot, we [couldn’t] just set something up. We all had to basically point and shoot.”

The students practiced in Currier Quad, where one would hold up a paper sun that was cut to the same shape and size the sun would be during the moment of totality while the other would try to capture the highest resolution photo they could as quickly as possible, Knowlton said. They continued to adjust their camera settings in the hours before totality to rapidly take multiple images at various exposures, allowing them to capture intricacies that can only be seen at a certain light setting.

After months of planning and preparation, Knowlton still had the opportunity to enjoy the beauty of the eclipse. “I remember [one of Pasachoff’s colleagues on the trip] said, ‘We have a minute and 50 seconds to take images of this eclipse,’” Knowlton said. “‘Take 10 seconds [to] just put your camera down and look at it for a second because it’s really cool.’ And so I took an opportunity to view the eclipse with my own eyes — not through a camera lens. And it was absolutely amazing.”

After Pasachoff’s team landed, they got to work developing a composite image — an image made up of multiple photographs. They used photo editing software to merge images taken at each exposure and correct image imperfections, such as dust on the camera lens or dead pixels. “The process of building composites is both a science and an art,” Knowlton described.

This image was featured in a press release put out by NASA five days after their trip, and it will be used by researchers to continue to refine future eclipse predictions.

Upon reflection, Knowlton acknowledged the sentimental nature of his journey to see the eclipse, as these astronomical events have bookended his Williams career. In the summer of 2017 when he was an incoming first-year and prospective astronomy major, Knowlton and his dad traveled to see the eclipse that crossed the United States. “I began my Williams experience seeing an eclipse, and I ended it also going on this research trip with Jay,” he said.

While Pasachoff has plans to continue his eclipse-watching in the coming years, Knowlton said he is unsure when he will get another opportunity. “If Jay ever asked me to go on another eclipse trip with him to provide my help, I’d be more than happy to do that,” he said.

But as of now, Knowlton said that he is looking forward to the 2079 total eclipse that is projected to cross Williamstown. “2079 will be a crazy year for the Astro department,” he said. “I’ll be 81, so I can totally make it.”