Acclaimed FB coach Dick Farley pens memoir with Dick Quinn

December 8, 2021

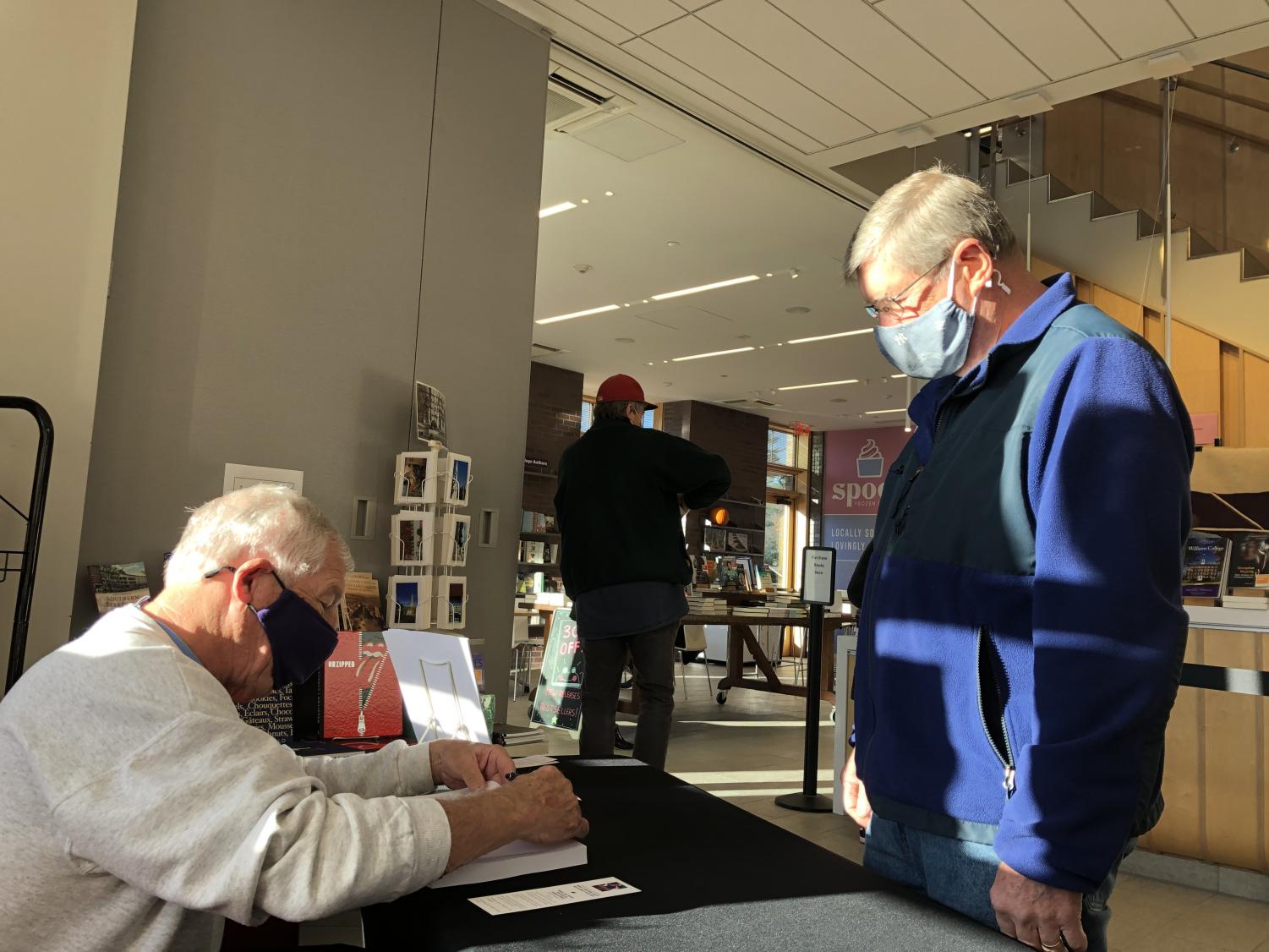

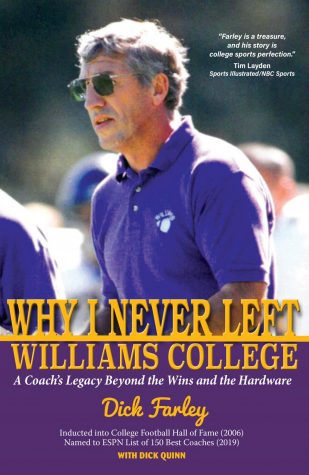

On the morning of this fall’s Homecoming — hours before the kickoff of the football game at Farley-Lamb Field — former football and men’s and women’s track coach Dick Farley settled into his seat at the College Bookstore. Farley was there to do a book signing of the newly released Why I Never Left Williams College, a memoir he wrote with Director of Sports Information Dick Quinn that Farley self-published on Nov. 6.

A legendary coach at the College and an inductee into the College Football Hall of Fame, Farley had drawn quite a crowd by the time the signing began at 9 a.m. Much to the surprise of Farley — and hardly anyone else — the line remained steady, extending the meet and greet from the planned two hours to four. By the time it ended, Farley had missed the football game’s first three downs and had to run over to the field (which is named for him) to catch the rest of it.

The book is the culmination of a decades-long career coaching at the College and countless accolades for Farley, who came to the College as the coach of track and assistant coach of football in 1972. The premise is simple: Farley moved out to Williamstown from his hometown of Danvers, Mass., with plans to stay for a couple of years before moving on; instead, he never left. Since retiring in 2003, he has remained in town, frequenting athletic events and visiting campus often.

Quinn, his co-writer, who himself has been at the College for over 30 years, said the book’s title is also a reference to the many, many inquiries Farley has gotten over the years about when he would leave Div. III athletics for a more high-profile athletics program.

As Farley writes in the book, leaving the College never made much sense to him. At larger schools, he noted, coaching involves pushing athletes to specialize in football and a great deal of administrative work, like fundraising. The two-sport coach said being at the College allowed him to focus on coaching and working with a range of athletes on three different teams, something he said he always cherished. “I didn’t raise money at Williams — that’s not what I was paid to do,” he said in an interview with the Record. “I was paid to coach sports and educate young people.”

From Quinn’s perspective, the well-rounded experience of athletics at Williams played an instrumental role in convincing Farley to stay. His affection for the College is evident in the book too, Quinn added. “It might be the last three or four pages where he’s thanking everybody from the grounds crew and the president, the athletic director — but also the faculty because of the courses and the way they taught, and how it just all comes together here,” Quinn said. “And, you know, that’s pretty much why he didn’t leave.”

Quinn noted that it is unusual for such a successful coach to remain at a small, Div. III college for so long. It is especially unusual, he noted, for someone as renowned as Farley, who was inducted into the National Football Foundation’s Hall of Fame in 2006 and named in ESPN’s list of the 150 greatest college football coaches of all time in 2019.

The enduring buzz about Farley’s coaching abilities is understandable in the context of his career stats. During his tenure as head coach between 1987 and 2003, the College’s football team went 114–19–3. This included five perfect seasons and positioned Farley with the sixth-best career record of all time in college football when he retired in 2003.

Farley made the decision to write a memoir four years ago, partly because of Quinn’s insistence that he commit his one-of-a-kind story to writing. Asking Quinn to co-write felt like a natural fit, Farley said, especially given his knowledge of Eph athletics and its history. The duo, who have been friends for three decades now, started revisiting Farley’s stories, placing them within the broader context of athletics statistics and the team’s trajectory.

“Every situation I asked [Farley] about, he never blinked and he told them,” Quinn said. “There’s some embarrassing moments. And he just said, you know, ‘This is what happened and I probably wouldn’t do it today. But I did and people saw it, so I can’t really deny it.’ That’s who he is. He’s very straightforward and open.”

While Farley may not have side-stepped questions about coaching slip-ups, he is noticeably bashful in addressing his own success. When asked about his career record, he said, “We had a fair amount of success, I’ll put it that way.” Farley did admit, though, that sometimes he is also astounded when he hears his stats read aloud or witnesses a former player reliving the success they shared. “If you were talking about somebody else, that was pretty good, [but] I never looked in a mirror and said, ‘Well, you know, you’re one of those guys that did a lot of this kind of stuff,’” he said.

Then there is the matter of Farley-isms, a nickname Quinn and others coined for a number of oft-quoted sayings Farley has been known to spout off. Some include: “Nothing good happens after midnight,” “Don’t get a big head, because if you’re any good, you wouldn’t be here,” and “Three hours to play, a lifetime to remember.”

Farley’s blunt humor is indicative of his no-nonsense approach to coaching, Quinn said. Throughout his career, according to Quinn, Farley has made clear that hard work and success are intrinsically tied. “All he ever expects from any of his athletes — football or track and field — is that, when they show up to practice, they give their best effort,” Quinn said.