‘Competing Currents’ opens at the Clark

November 17, 2021

The Clark Art Institute opened Competing Currents: 20th-century Japanese Prints on Nov. 7. The exhibition was curated by Oliver Ruhl, who graduated from the College’s master’s program in art history in 2021.

On view in the Clark’s Eugene V. Thaw Gallery until Jan. 30, 2022, the exhibition explores the intertwining nature of two revivalist woodblock print movements in Japan — shin-hanga (new prints) and sōsaku-hanga (creative prints). Ruhl developed the exhibit during an internship at the Clark while he was a student at the college.

Now based on the West Coast, where he is a PhD candidate in Japanese art history at UCLA, Ruhl presented these two variations on Japanese woodblock prints in a virtual opening lecture Saturday afternoon. In the lecture, he said that “[Shin-hanga] was defined by a nostalgia for the premodern while [sōsaku-hanga], rejecting the past entirely, embraced modernist and avant-garde sensibilities.”

Yet after walking through the gallery entrance, the first piece to the right is neither shin-hanga nor sōsaku-hanga. Rather, this prefatory piece, Kintai Bridge at Iwakuni in Suō Province (1859) by Utagawa Hiroshige II, introduces the context and style of the ukiyo-e tradition from which the two subsequent movements bloomed. As the exhibition explains, woodblock prints flourished during Japan’s Edo period (1615-1867) with ukiyo (the floating world) — the new capital’s ethereal urban lifestyle — as inspiration. Thus, ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) often depicted sensuous scenes of nightlife and leisure, although landscape scenes were popular too.

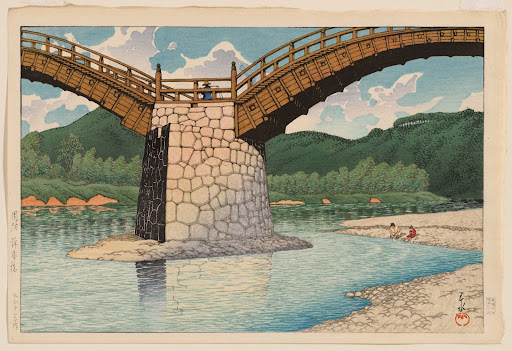

Hiroshige II’s flattened depiction of Kintai Bridge in saturated colors with a dreamy dusting of snow embodies the ukiyo-e genre. However, to the right of Hiroshige’s work hangs The Kintai Bridge in Suō Province (1924) by Hasui Kawase. While both prints feature the same bridge, the former exemplifies stylism over realism and the latter, created 65 years later, highlights shin-hanga artists’ modern approach to nostalgic themes.

“Printmakers were forced to reckon with the legacy of ukiyo-e, new influences of the European tradition of art making, and the demands of a rapidly evolving global market,” Ruhl said.

Due to these factors, shin-hanga was a highly commercialized exchange between artist and patron, with a publisher acting as a middleman. During the opening lecture, Ruhl focused on Hasui Kawase and his legacy as an artist for publisher Shōzaburō Watanabe. Ruhl highlighted Hasui Kawase’s Tokyo (Santa in the Snow) (1950), which was not in the exhibition. The scene sets a picturesque snowy scene reminiscent of old Japan disrupted by a distinctly Western, red-suited Santa lugging a sack. Tokyo (Santa in the Snow) was published in the The Japan Trade Monthly.

Ruhl said that these commercial overtones were common in shin-hanga. “The insertion [of a Santa figure] no doubt reveals an awareness of Western taste and reception, as well as a true desire to cater to those tastes through a modulation of subject matter and imagery,” Ruhl said.

In this sense, Ruhl regards enterprise shin-hanga prints as partly the brainchild of the publisher and, more broadly, the product of a team, which also included artists, carvers, and printers.

Moving past the ukiyo-e works at the exhibition’s entrance, Ruhl develops this story of scenes from the past redefined through Western-influenced realism and Japanese industrialization in the first room. Four more Hasui Kawase prints line the back wall, three of which are painted with moody skies, and all of which exemplify the realism of shin-hanga.

The transition from the first room to the second is a transition from shin-hanga to sōsaku-hanga. “In many ways, sōsaku-hanga was conceived in total opposition to shin-hanga,” Ruhl said at his lecture.

Sōsaku-hanga artists valued individualism, adhering to the notion of “jiga, jikoku, and jizuri” — self-drawn, self-carved, and self-printed. “Inspired by native folk art traditions, as well as the Western concept of the artist as a solitary creative, sōsaku-hanga artists emphasize that their art was the result of the labor of a single artist, rather than that of a collaborative team of artisans,” Ruhl said.

Inherent in sōsaku-hanga’s individualism is a large range of styles that constitute the nebulous movement. Indeed, experimentation with materials, design, and subject matter characterizes the style. Thus, the pieces in the second room vary from Kiyoshi Saitō’s bold collage-like prints like Maiko, Kyoto (1961) to the playful patterns and pink in Hashimoto Okiie’s Young Girl and Iris (1952). Also in the second room is a small case displaying an unfinished print, several layered wood blocks, carving tools, and a special disk tool to transfer ink to the paper.

From beginning to end, Ruhl’s exhibition clearly unfolds the two competing wood printing styles influenced by the Edo period’s ukiyo-e movement. Ruhl said that the exhibit explores “two oppositional yet deeply intertwined movements that rekindled a passion for Japanese printmaking, both domestically and abroad in the 20th century.”