Sawyer zine collection celebrates creativity, community

November 17, 2021

The first time I walked into the lobby of Sawyer Library, I expected shelves upon shelves of books, but I encountered something completely different: oil-slick male bodies with collaged cat heads, tips for do-it-yourself (DIY) car repairs, and a “list of objects that aren’t masks.” Flipping through the zine collection, I felt 7 again, browsing the stash of worn books and old magazines my parents kept under their vanity table. It felt like coming home.

According to the ZINES homepage of the College’s library website, zines — pronounced zeens — are “small-circulation self-published works of original and/or appropriated text and images, that are usually reproduced through an inexpensive and easily accessible means (e.g., photocopy or risograph).” One brush with the zine collection and one can see this clearly: most are printed on regular print paper of varying sizes, many photocopied, hand-drawn, or handwritten.

The zine collection at the College was created in 2018 in response to “flyers with xenophobic, white supremacist, and anti-Semitic messages circulating in Sawyer library,” according to the ZINES homepage. Reference and First-Year Outreach Librarian Hale Polebaum-Freeman, who is the director of the zine collection, said that “many of the zines in the circulating collection are authored by zinesters who identify as members of a marginalized community, whether that be [people of color], LGBTQ+ individuals, people with disabilities, or those who hold intersectional identities. These are voices that are often missing or underrepresented in more traditional spheres of publishing, including academic publishing.”

Polebaum-Freeman said they believe the introduction of zines has helped make the library a space for community-building and gives students an opportunity to discover new interests. Unlike library books, the zines aren’t systematically organized. “The circulating zine collection lacks the traditional organization structure that one might expect to find in a library, and instead encourages exploration and serendipitous connection with the materials,” they said.

Another difference from the rest of the library is that anyone can contribute to the collection, and all forms of zine-making are welcomed, from the glossiest print spreads to small folded pages made from letter-sized paper. “The DIY nature of zines extends into the publication process, breaking down barriers for individuals who haven’t felt welcomed or worthy within traditional and/or academic publishing communities,” Polebaum-Freeman said.

Beza Lulseged ’25 was first acquainted with zines in her junior year of high school. Even though she was not a student at the College when the hate messages were circulated, she agreed that zines are a powerful tool to uplift marginalized voices. “Being a Black woman and getting the chance to express my creative side in a way where I have full authority and not being told exactly what to do — all of this is coming from my mind and I’m curating and using the work that I want,” she said. “I think exhibiting that, in such a white space, in such a white college and institution, is already a big feat.”

Lulseged said she approaches zine-making with a curator’s eye, aiming to bring together her peers’ diverse perspectives and practices. “I started up an Instagram account, naturally, and told my friends about it, who told their friends,” she said. “And then it turned into this thing where other small zines were reaching out to me and supporting me through DMs and reposting my work, telling people about my submission deadlines.”

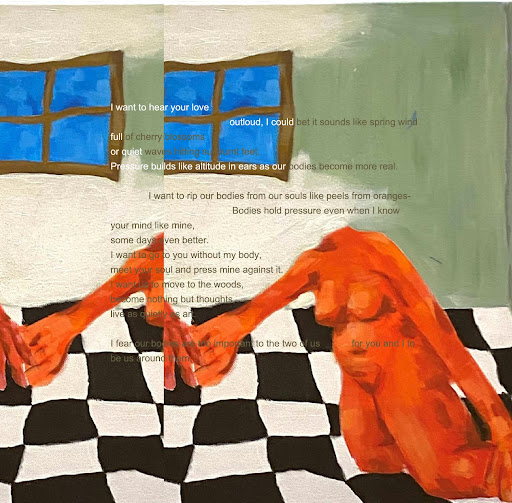

Lulseged’s zine in the library’s collection, February Feeling, is centered around the feeling of youthful love, carefully seamed together from photographs, artworks, and literature from multiple contributors. In many ways, the zine collection at the College is a microcosm of Lulseged’s Instagram community — a place where readers meet zines, and zinesters meet one another.

Fellow student zinester Alice-Henry Carnell ’22.5 said that “the great thing about zines is that it lets you explore what you’re really interested in… It’s such a mutable medium.” Carnell has experimented with this mutability themself: Their zines range from long to short, informational to poetic, public-facing publications to private gifts. One of their zines, The Insect Obsession, is funded by the Center for Environmental Studies and is a speculative retelling of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the virus reimagined as a cicada. Carnell also works at Sawyer’s Fabrication Lab, where they help introduce other students to the process. They recently hosted an environmental zine-making workshop in collaboration with the Williams Environmental Council.

The openness of zine-making appealed to Hannah Bae ’24, who encountered zines in WGSS 101 as a means for activism. As a summer fellow at the Center for Learning in Action (CLiA), she attended a zine workshop led by Polebaum-Freeman where she looked at zines from the collection and learned about zine-making history. “That workshop was just really enlightening, learning about this new type of media, and the activist work that’s centered around it from a creative approach,” Bae said. “That was probably the first time that I was introduced to something that I could partake in or that I can adopt a style for myself.”

Not everyone interacts with zines regularly, however, partly because few know there is a zine collection at the College, she said. “I think for the most part the only times I’ve really seen students engage with zines were in facilitated spaces,” Bae said. “The biggest example would be the [CLiA] workshop in zine-making: I think that was probably the first time that a lot of us had really heard about the zine collection at Sawyer.”

For Lulseged, the modest size of the zinester community at the College doesn’t stop it from providing a refuge. “In our most vulnerable and stressed-out times, people normally seek to do something creative or to do nothing,” she said. “But why do nothing when you can do something creative, you know?”

Zines are not just a means for representation, Carnell said; the medium can also foster communication. “Because of their small circulation, it is really community-focused,” they said. “It’s really powerful to have such an accessible and easy-to-use tool that a community can distribute amongst themselves.”

Carnell said they hope students see zines as “resources as legitimate as the other volumes in the library.” “There’s so much that you can learn from a zine,” they said. “Even if it’s not a book published by Oxford University Press, there’s someone who has knowledge and passion and their own expertise.”