Review: ‘Iphigenia’ at MASS MoCA

November 10, 2021

About 15 minutes into Friday’s performance of Iphigenia — a new opera with music by Wayne Shorter and words by esperanza spalding that previewed at MASS MoCA this weekend — it began to sink in that I was, in fact, at an opera, and would be for the next 105 minutes. Why, then, was I shocked to find myself listening to burly tenors bellow indecipherable libretto, even though Iphigenia was explicitly conceived of and advertised as an opera?

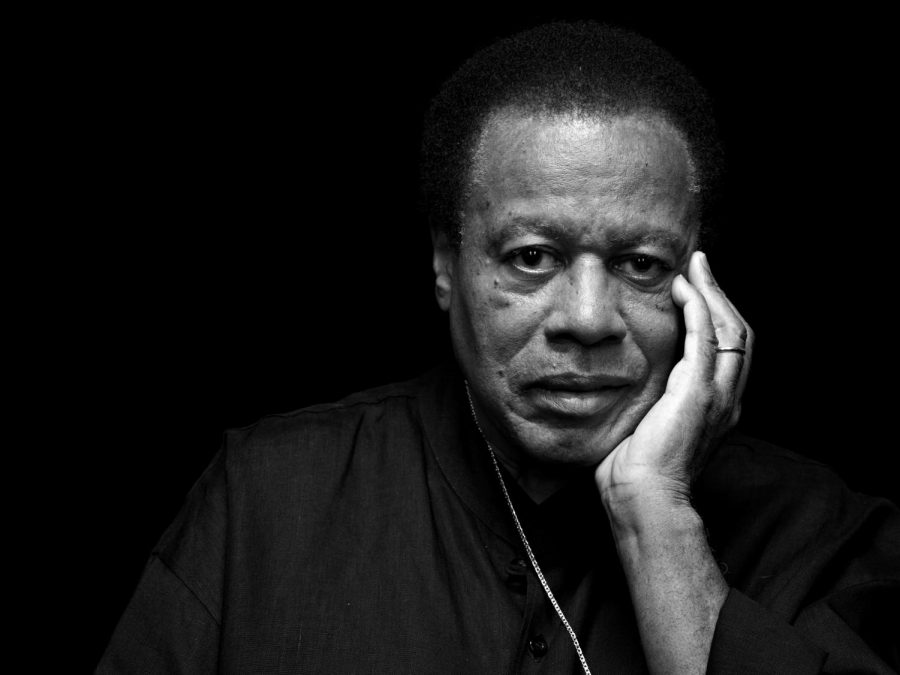

A paragraph in my defense, your honor. I had many reasons to presume spalding and Shorter’s opera might not be so, well, operatic. Shorter and spalding are both known for their contributions to jazz music rather than classical composition. Shorter, a saxophonist who played in the Miles Davis Quintet, has been called “a contender for greatest living improviser” in the New York Times; spalding is a bass prodigy and jazz vocalist who became one of the youngest instructors in the history of Berklee College of Music when she joined the faculty at age 20.

Iphigenia is a multigenerational collaboration between the 88-year-old Shorter, whose lifelong dream to compose an opera became threatened by his declining health, and 37-year-old spalding, who took a year off from her current teaching post at Harvard to help make Shorter’s dream a reality. Iphigenia introduces improvisational jazz to classical operatic form, promising an “intervention into myth-making, music, and opera as we know it,” according to an advertisement. Intervene it certainly did, but on terms far more traditional than one might have hoped for from such visionaries.

Iphigenia takes the Greek myth of Iphigenia at Aulis, canonized by the classical tragedian Euripedes in a play of the same name, as its point of departure. During preparations for the Trojan War, King Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek army, accidentally slays a sacred deer of the goddess Artemis. In retaliation, Artemis withholds the winds that Agamemnon and his troops need to set sail for Troy unless Agamemnon sacrifices his daughter Iphigenia to the gods.

In their imagining of the Iphigenia myth, Shorter and spalding sought to upend operatic and mythological tropes which condemn women time and again to tragic fates. “No more tragic women singing through suicide and going mad in perfect pitch,” the press release for the project states. “No more spectacles of women dead and dying.” Yet Act One of Iphigenia portrays just this. For what feels like an exceptionally long time, men in Greek helmets whoop and holler, slitting women’s throats, stomping in phalanxes, and brandishing red solo cups. Presumably, forcing the audience to endure such repetitive and traumatic exposition raises the stakes of the pivot that occurs within Act Two. It felt unnecessary, however, to spend so much valuable performance time setting up a reckoning the audience already knew was to come — the show begins with an usher assuring us that “this myth will have a different ending.” In Act Two, five alternate versions of Iphigenia who were slain violently in Act One — Iphigenia Unbound (Kelly Guerra), Iphigenia of the Sea (Joanna Lynn-Jacobs), Iphigenia the Elder (Sharmay Musacchio), Iphigenia the Younger (Nivi Ravi), and Iphigenia of the Light (Alexandra Smither) — take the empty stage to tell their stories, heal together, and advise the soon-to-be-sacrificed Iphigenia of the Open Tense (spalding herself) to compose a new fate for herself.

In Act Three, this agency takes the form of a musical concept referred to by spalding as “open tense.” Music usually involves the reiteration or rewriting of preexisting historical forms, but “open tense” music — in Iphigenia, call and response improvisations from the vocalists and orchestra — is grounded in the present by engaging “the art of listening and responding deeply and at the same time.” The narrative of Act Three picks up with Iphigenia’s impending sacrifice, but spalding’s Iphigenia has been empowered by her exit from the opera’s action and is now prepared to change her fate. Iphigenia concludes not with the singular tragedy of spalding’s onstage sacrifice, nor with a climactic and explicit refusal from spalding, but with spalding leading a communal mourning ritual for all five Iphigenias in “open tense.”

A work in progress is an awkward thing for an opera to be. Fully mounted operas rely on lavish sets, costumes, and staging to match the intensity of the vocal performances and orchestral arrangements; opera readings forgo these theatrics to foreground the human voice. Iphigenia’s production quality lay somewhere in the muddled middle, confusing the opera’s mission. Is Iphigenia, with its elaborate sets and full symphony orchestra, supposed to be an all-out full production? Or are the classical theatrical elements of Iphigenia present chiefly to be deconstructed and critiqued, held as a counterpoint to spalding’s inventive, yet under-utilized vocals? Although Iphigenia was a brave attempt to straddle the line between traditionally overstimulating classical opera and radically intimate improvisational jazz, the performance ultimately skimped on the latter despite intending to center these new possibilities for the form.

It’s worth noting that the word “opera” comes from the Italian word for “work” and it shouldn’t be overlooked that Shorter’s composition of Iphigenia was a monumental labor of love. Nearing 90, Shorter composed the music for Iphigenia entirely by hand, after recovering from a metabolic tremor that made playing his beloved saxophone and handwriting music difficult. But at the end of Iphigenia, Shorter’s meticulous composition dissolves back into improvisation. The conductor’s hands fall silent; he stands in awe. Shorter’s parting gift is perhaps not the music of Iphigenia, but rather a willingness to open this score up to radical improvisation, to pass the baton over to spalding and the cast of women who represent the vanguard of jazz. The great thing about a work in progress, Iphigenia suggests, is that the most interesting work is just beginning. represent the vanguard of jazz. The great thing about a work in progress, Iphigenia suggests, is that the most interesting work is just beginning.