When the College named a dorm after an alleged mutineer

November 10, 2021

A few weeks ago, I wrote an article about a library in Spencer House, named after Philip Spencer. I noted at the end that I could find no information about a Williams-affiliated Philip Spencer on Google or in the College library database. “Maybe the house is all that is left of his legacy,” I concluded.

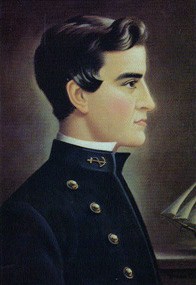

Rarely have I ever been so wrong. While Spencer’s final days are shrouded in doubt, he is not a man who will be lost to history. So, who was Philip Spencer, and why could I find nothing about him?

The answer to the second part of that question is as simple as it is perplexing. Spencer did not attend the College, nor was he a faculty member or donor. He never so much as set foot on the campus in his admittedly short life. Out of every building the College has named after a person, Spencer House is the only one named after someone with no apparent connection to the College (and no donation made).

When the College announced the naming of Spencer House in 1909, several alums sent letters to the College expressing concerns. Spencer, they complained, was not someone the College should be naming a building after — and not just because he had no ties to the College. On Dec. 1, 1842, according to a 1939 The New Yorker article, Spencer was hanged at sea for a mutinous plot to murder his captain and take control of the USS Somers. Had he succeeded, this would have been the only mutiny ever to take place aboard a U.S navy ship.

The son of President John Tyler’s secretary of war, Spencer attended Hobart College, then called Geneva, but was expelled for poor grades. He later enrolled at Union College, where he co-founded the Chi Psi fraternity, which partially explains why there is a building named after him at Williams; Spencer House was the home of the College’s chapter of Chi Psi.

According to The New Yorker, while at Union, Spencer’s favorite book was Charles Ellms’ The Pirate’s Own Book, which tells of the bloody exploits of famous pirates. Never much interested in formal learning, Spencer soon quit Union College and followed his nautical dreams, ending up aboard the Somers, a training ship for young members of the Navy captained by Alexander Slidell Mackenzie. Ironically, according to the College archives, Mackenzie’s son, Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, Class of 1859, later attended the College and was a member of Chi Psi’s rival fraternity Kappa Alpha.

On Nov. 25, 1842, Lieutenant Guert Ganesvoort told Mackenzie that the purser’s steward, J.W. Wales, had said there was a mutiny brewing aboard the Somers, and Spencer was the ringleader. Possibly, Spencer was motivated by the fact that, according to his own notes on the subject, Mackenzie administered 2,313 lashes to his crew during the voyage.

Incensed, Mackenzie immediately accosted Spencer. Spencer claimed he was joking, but Mackenzie didn’t believe him. Spencer and several men thought to be his co-conspirators were arrested and held in the ship’s brig, but that wasn’t enough for Mackenzie. A few days later, Mackenzie executed Spencer and two other sailors, Elisha Small and Samuel Cromwell. A jury, with express hesitance, later found Mackenzie not guilty of any criminal actions.

At Mackenzie’s trial, the captain advanced much evidence against Spencer, but Spencer himself never had a formal trial or any chance to mount a defense prior to his execution, so there was no one to push back against Mackenzie. According to the official record of the trial, Wales claimed Spencer had tried to convince him to join a conspiracy that aimed to “murder all the officers, take the brig, and commence pirating.”

During the trial, Wales claimed that Spencer had sketched the Somers flying a pirate flag and had smuggled banned tobacco onboard to woo other sailors to his cause. Mackenzie even claimed that Spencer confessed to the crime.

Spencer’s defenders responded that the entire thing was a harmless joke taken out of proportion by Wales and spun into a grand conspiracy by the paranoid Mackenzie. Among Spencer’s most ardent supporters was the author James Fenimore Cooper, who published an 88-page account of Mackenzie’s trial that excoriated the captain.

Trial records show that after Spencer was detained, his cabin was searched, and a sheet of paper was found in his razor case with a list of names written in Greek letters, divided into “certain” and “doubtful.” That the names were written in Greek was used as proof that Spencer must have been hiding something — why else use Greek? — but this, too, is debated. U.S Naval Academy professor of history Phyllis Culham has argued that writing in Greek was normal for the classically educated at the time.

In any case, the names that are on the list under “certain” encourage further examination. They include Andrews, a name belonging to no one on the ship, and Wales, the main witness against Spencer at Mackenzie’s trial. But, according to Culham, they do not include Small or Cromwell, the two men executed alongside Spencer. In fact, Cromwell’s name is not on the list at all.

Regardless of whether his execution was justified, it was Spencer’s death that made him a legend. Boldly ignoring all evidence, Chi Psi men invented their own version of events, one in which Spencer’s list of names concealed hidden fraternity secrets and he refused to renounce the fraternity even to death. One in which his final words were a defiant cry of allegiance to his brothers. One in which, instead of being hanged, he walked the plank — like the pirate he had always fantasized of being.

To offer insight into the mindset that led the College to name a building after Spencer, I will close with an excerpt from the lengthy ode Chi Psi composed in his honor:

O here’s to Philip Spencer

Who when about to die

When sinking down beneath

the waves

Loud shouted out Chi Psi!

So, fill your glasses to

the brim,

And drink with manly pride

Humanity received a blow

When Philip Spencer died.