Hidden library in Spencer House provides glimpse into the College’s history

October 20, 2021

The College’s libraries are home to 768,252 books, according to the College’s website. However, scattered across campus, in professors’ offices and in glass-walled conference rooms, are a plethora of libraries in miniature, eclectic collections of books that the College doesn’t catalog. One of those miniature libraries, tucked away in a dimly lit room in Spencer House, offers a look into College life from the distant past to the present.

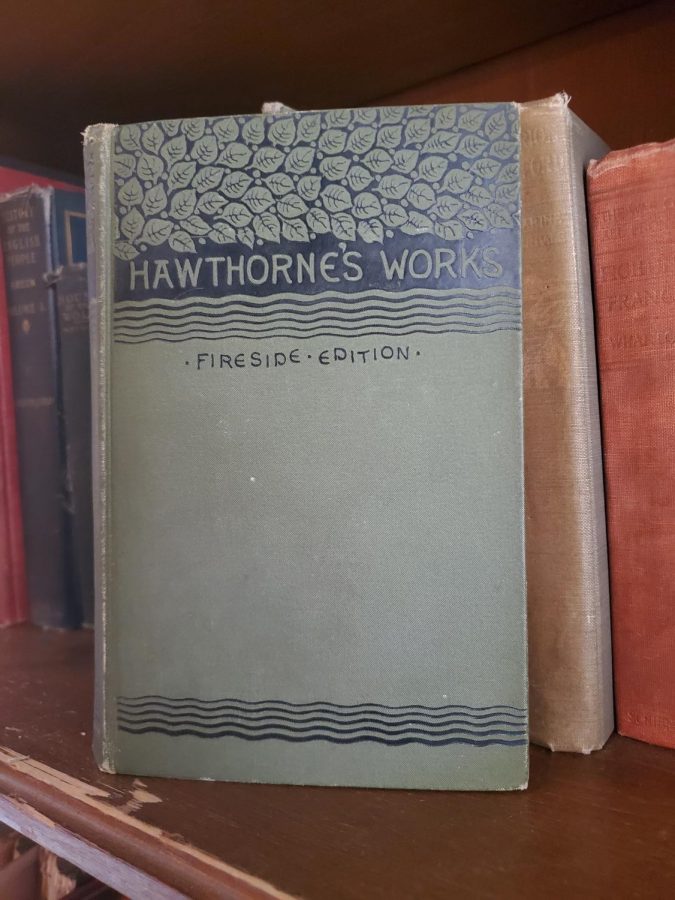

By my count, the Spencer library contains 647 books. The content of these books is as varied as their ages, ranging from romances to Greek grammar guides to poetry collections to The Witch of Prague to Majority Leaders in the U.S. House. The oldest book is 132 years old, and the newest came out two years ago.

“I don’t know how useful [the books] would be for classes,” Spencer House resident Nick Servedio ’22 said. In part, he said, this is because the books are not organized. Never mind the Dewey Decimal system; these books are not sorted alphabetically or even arranged by genre. The library contains three copies of The Novels of Balzac, and none of them are in the same bookcase.

No librarian has catalogued the shelves of the Spencer library or attempted to impose order among the chaos, as far as Director of Libraries Jonathan Miller knows. In fact, according to Miller, the College’s official libraries have no record of the Spencer library whatsoever.

This might mean that the Spencer library isn’t, well, a library. “What separates a library from a bunch of books in the same room is the issue of organization,” Miller said. “But frankly, there’s no law — there’s no rule about how to use the word.”

Whether or not the room is technically a library, Servedio said students don’t often use it as such. He speculated that the books belonged to students who lived in Spencer in days gone by. Sitting on the armrest of one of the room’s couches, he sketched a dramatic vision of who might have once used the library. “I’m sure some secret society groups on campus used this as a meeting point,” he said.

I imagined one of these societies gathered by the light of the library’s fireplace, surrounded by leather-bound books, speaking in hushed tones.

The Record could not verify whether secret societies had ever met at Spencer House, but it was indeed home to the Chi Psi fraternity for half a century after its construction in 1909. The fraternity ceded the house to the College in the late 1960s after the abolition of fraternities.

It is not just the ambiance of the Spencer library — the frayed spines, the fireplace, the smell of old paper — that makes it what it is. Each of these books is a story. Not just the literal story between the covers, but also the story of the person who owned them. Often, these people left inscriptions, their words now a piece of history.

Many books have names inside the cover, like a French spelling book belonging to one D. Roberts. Some of the marks are mere questions, hanging in the ether, like the math problems scrawled on the cover of one old paperback: “1730 – 1500 = 230.” What prompted this hurried equation? Why is it written in the front of a poetry collection?

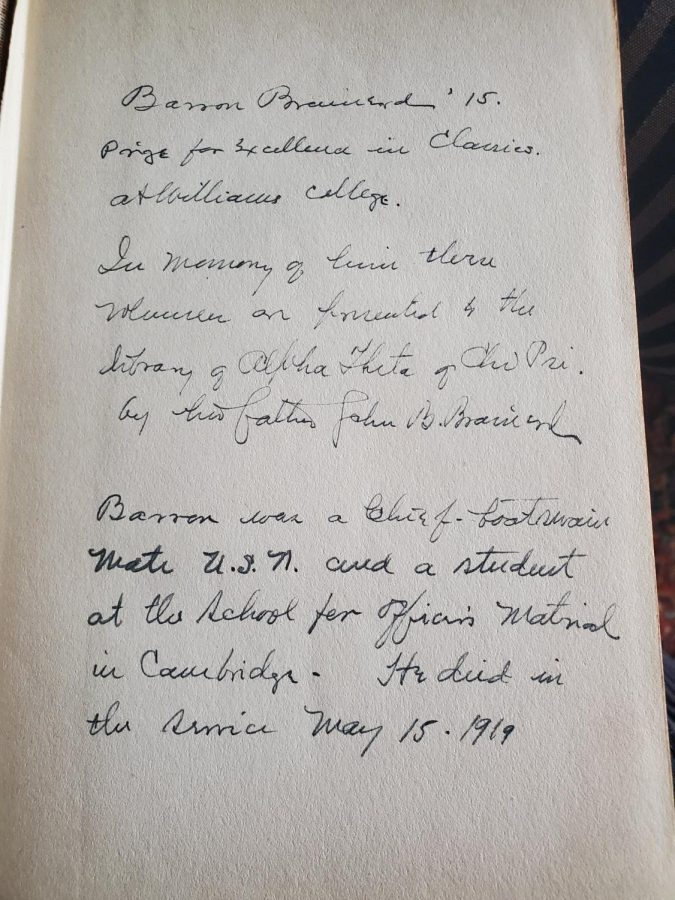

Others contain recollections of former students. “Barron was a chief of boatswains … and a student at the school for affairs national at Cambridge,” reads one inscription, in part. “He died in the [military] service [on] May 15 1919.” I was able to find Barron Brainerd, Class of 1915, in a digitized copy of a book commemorating Harvard students who died in World War I. A member of the Chi Psi fraternity, he was an editor at the Record, he loved flowers, and he once saved two boys from drowning. He died at 26. I could not find any of the other names I saw in inscriptions, those fading pencil lines their lingering mark on history.

Among the collection are several yearbooks, and from these, it is possible to get a glimpse of long-gone generations of Williams students. “The brutal Hayden is another holy terror from Kiski,” reads a tongue-in-cheek description of Hayden Robinson, Class of 1917. Another page bemoans a disappointing year of golf: “An unsuccessful season of five consecutive defeats was hardly redeemed by the single victory over the traditional rival: Amherst.” The “A” in “An” is illuminated like the first letter in a Gutenberg Bible.

The newer books added to the Spencer Library line the bookshelf nearest to the entrance. Most are for college courses, but some aren’t, like a Dan Brown thriller. It is possible to glean a little information about the students who left these books: the classes they may have taken, their taste in fiction.

But neither the inscriptions nor the books they decorate are eternal monuments. Spines crack, pages crumble, pencil fades. In official libraries, these books would face an uncertain future. Miller explained that depending on their value, their relevance, and how many other copies exist, the books might be preserved — or not. “We may well discard the book,” he said. However, in Spencer, the books will not be preserved or discarded. They may not even be touched.

Many books are missing covers, and many notes are illegible. Some pages are so brittle I dared not turn them, and other books I left on the shelf for fear their pages would scatter across the floor should I try to remove them. Thick black dust coats other volumes, staining my fingers like charcoal. When I tried to look at a French play, the cover peeled off and stuck to a copy of Tristan and Iseult.

Spencer House is named after Phillip Spencer, but I could find nothing about him on Google or in the College library database. Maybe the house is all that is left of his legacy, stripped to a name, like D. Roberts in the French speller.