WCMA hosts talk with Christine Sun Kim

October 6, 2021

The Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA) welcomed visitors this fall with the Sweaty Concepts exhibition, organized in partnership with the Feminist Art Coalition. The exhibition includes more than 100 artworks from about 50 artists and showcases the range of experiences that come from finding comfort in new places or, as best explained by feminist scholar Sara Ahmed on WCMA’s website, an experience “that comes out of a description of a body that is not at home in the world.”

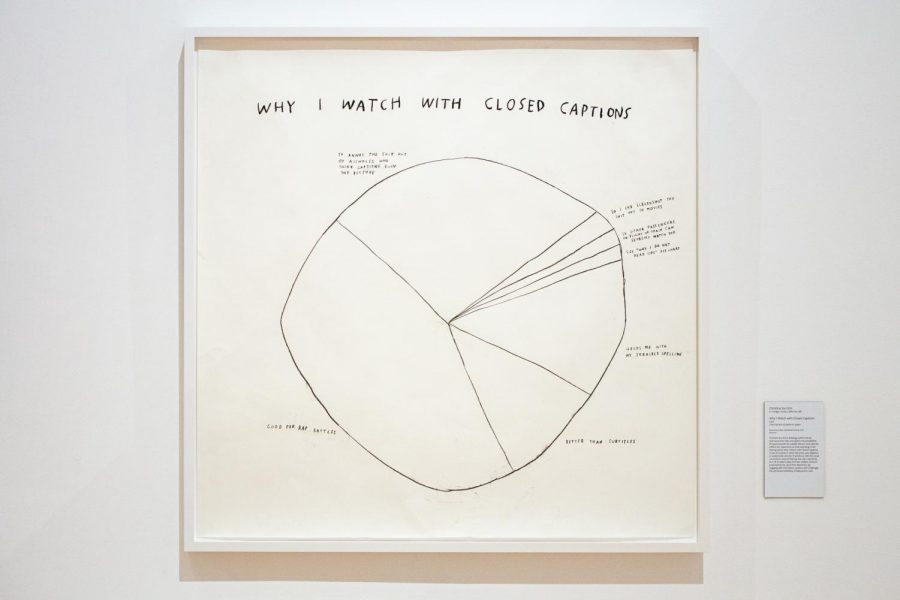

Sound artist Christine Sun Kim, whose artwork Why I Watch with Closed Captions is featured in the exhibit, spoke at WCMA’s Artist Talk event on Sept. 23. She highlighted her extensive works — ranging from performances to charcoal and oil pastel drawings — and shared her experience as a member of the Deaf community. The talk included American Sign Language (ASL) interpretation with the support of various offices on campus.

The event was hosted by WCMA Director Pamela Franks, who began the talk with a brief introduction of the exhibition, and Sweaty Concepts curator Lisa Dorin, who introduced Kim. “[Kim’s] works questions established forms of communication, such as language that is both spoken and signed, and calls attention to the hidden quirks and dissonances built into those systems that are so often predicated upon being able to hear,” Dorin said.

Kim started her talk by sharing her newfound fascination with the shapes of signs and how they can be captured visually. She incorporated this concept in her recent thematic works revolving around her interpretation of the future for the Deaf community. “Even to this day, [Deaf people] are still struggling in fighting for their most basic right, to get better captioning on TV, to get an interpreter,” Kim said. “I am hopeful that in the future, we will see the opportunity to not only express ourselves, maybe through poetry, but also through image, also through video.”

Kim demonstrated this idea through her series of visual works that reference the sign for “future.” The series has since appeared in venues such as the 11th Shanghai Biennale — an internationally acclaimed contemporary art event — and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

Kim’s vast oeuvre also includes works that reflect her motherhood in conjunction with Deafness. Kim said that one of the struggles she faced was “balancing spoken language with signed language” in her home, since “spoken language tends to usurp … in the household.” Navigating this led to the creation of her musical piece One Week of Lullabies for Roux. The installation, held at the White Space Beijing booth, was inspired by the baby monitor she bought for her daughter Roux and the lullabies that were playable on it. Concerned by the quality of the lullabies, Kim instead collaborated with several friends, who were also parents, to compose seven lullabies with a “sound diet,” a term referencing the certain auditory limitations and criteria the composers followed — keeping the pieces quiet, for example.

Kim’s other works make use of angles and charts to provide commentary on her experience in the Deaf community. In these series, Kim emphasizes the difference between anger and rage. “Anger often is a response to, maybe, one isolated incident; whereas, rage is a reaction that is built over time, over our lifetime,” she said. One of the artworks showcased in the series was Degrees of my Deaf Rage in the Art World, which focused on angles. Alongside angles, pie charts, such as the piece in the exhibition, was another medium for Kim to communicate her thoughts.

In the final minutes of the artist talk, Kim answered a few questions from the audience. When asked about her relationship with technology and the smudges in her pieces, Kim detailed her artistic transition away from the auditory to one that blends sound with paper. “What’s interesting is that the paper is my reaction to my resistance to working with sound,” she said. In addition to the inevitability of messes when working with large pieces of paper on the floor, Kim explained the hidden purpose behind the smudges in her work as a reference to her conversations with hearing people. “When I interact with hearing people, there is no direct language — I instead have to find traces to put together.”

Another question concerned her identity as a Deaf, female Asian artist and the challenges she faced in her career. “I was more busy being Deaf than I had time to grow my Asian identity, and I always kind of felt like my Deaf identity took on more importance and more presence in most of my life,” Kim said. Silence was an expectation in both her identities, she said. “Both identities, being Deaf and Asian are typically seen as a passive identity, and sometimes I’m more of a threat in one way or another and how I’m threatened is dependent on who I’m with,” she said.

Despite these roadblocks, Kim has created for herself a space in the art world.