College releases data from survey gauging prevalence of and attitudes on sexual violence

May 19, 2021

Editor’s note: This article contains discussion of sexual assault.

Responses from the the College’s 2021 EPH Community Attitudes on Sexual Assault (EPHCASA) campus climate survey, sent to all students in February, indicate a decrease in the prevalence of most types of unwanted sexual contact compared to previous years. Director of Sexual Assault Response and Health Education Meg Bossong ’05 provided the Record with preliminary data from the survey.

The number of students who reported taking actions as bystanders, including helping an intoxicated friend get home or calling Campus Safety and Security (CSS) or the local police to intervene in a potentially unsafe situation, also decreased. This trend may be explained in part by COVID-19 restrictions on on-campus student life.

The EPHCASA survey was first created in 2015 to gather fully anonymous data about sexual and other intimate violence at the College, including students’ observations about campus climate, their level of engagement with prevention programs, and the prevalence of intimate violence.

The College conducted the survey for the second time in spring 2018 and will continue to do so every three years, so the first-years in one survey will be seniors in the next iteration, according to Bossong. “It’s so that we can have an index class over time and track things that way,” Bossong said.

The 2021 survey had 1,355 respondents for a response rate of 69 percent, based on 2020-2021 enrollment totals. Of the respondents, 49.4 percent identified as women, 47.9 percent as men, and 2.7 percent as nonbinary.

Reported prevalence of unwanted sexual contact

Bossong said that the College is experiencing trends that mirror national data in terms of who experiences sexual violence on campus.

“Trans and non-binary people experienced violence at much higher rates than cisgender people, and queer people are experiencing violence at or slightly higher than the rates that straight people are,” Bossong said. “Female-identifying folks are experiencing violence at higher rates than male-identified folks, but it is certainly not zero for male-identifying folks.”

The survey asked respondents to answer “No,” “Yes, once,” “Yes, more than once,” or “Unsure” to a series of questions asking whether they had experienced different types of unwanted contact while they were “a part of the Williams community,” including while studying away or traveling for athletics.

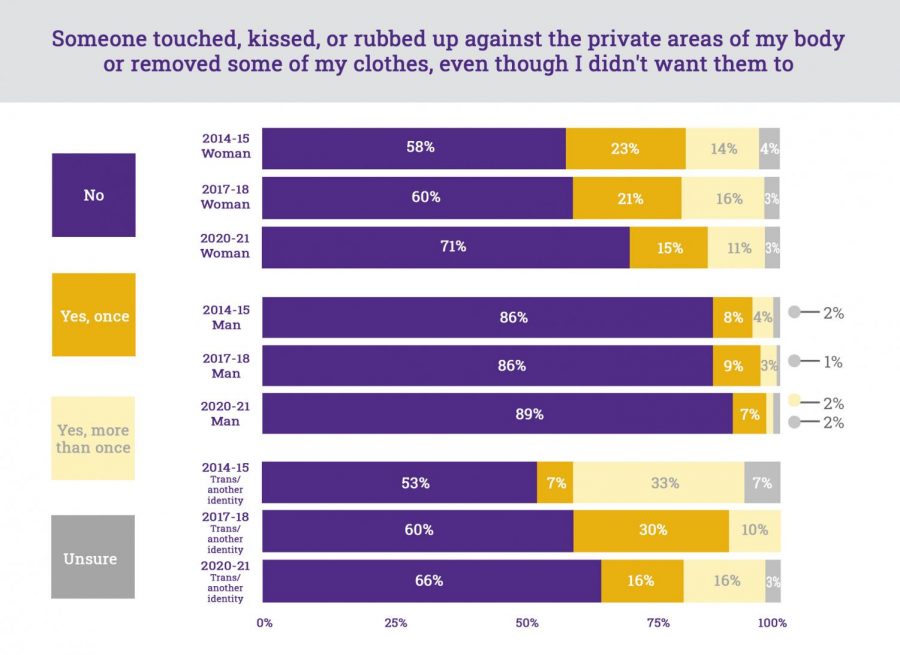

In the 2021 survey, 26 percent of women answered “Yes, once” or “Yes, more than once” to a question asking whether “someone touched, kissed, or rubbed up against the private areas of [their] body or removed some of [their] clothes without consent,” compared to 9 percent of men and 32 percent or respondents who identified as trans or another identity.

In response to whether someone tried to engage in penetrative sex without their consent, 7 percent of women indicated this had occurred at least once, while 3 percent of men and 5 percent students who identified as trans or another identity said so.

Six percent of women said someone had tried to engage them in oral sex at least once without their consent, while 2 percent of men and 12 percent of students who identified as trans or another identity said the same.

Four percent of women said someone had sexually penetrated them or made them sexually penetrate someone else without their consent at least once, compared to 2 percent of men and 9 percent of students who identified as trans or another identity.

Bossong also noted that the College has lower reported rates of intimate violence than national averages. “So violence of all kinds — sexual violence, dating violence, stalking — is happening less frequently at Williams than the national data suggests it is happening at colleges and universities broadly,” Bossong said.

Incidences of unwanted sexual contact for which Bossong provided data to the Record have also decreased across the board over time.

The proportion of respondents who said “someone touched, kissed, or rubbed against the private areas of [their] body or removed some of [their] clothes” without consent at least once fell from 25 percent in 2017-18 to 18 percent this year (across all gender identities).

The proportion of students of all gender identities who said someone tried to have penetrative sex with them without their consent at least once fell from 7.7 percent in 2017-18 to 5 percent this year. The proportion of students who said someone did have penetrative sex with them without their consent at least once fell from 5.6 percent to 3.2 percent over the same period.

The rate of unwanted oral sex and attempted nonconsensual oral sex across all gender identities also fell slightly over time from 3.1 percent and 5.2 percent in 2017-18 to 2.6 percent and 4.2 percent this year respectively.

The 2020-21 EPHCASA survey also asked students about dating violence victimization, as well as incidents of sexual harassment by faculty and staff. The proportion of students who said they had experienced various types of dating violence — including being yelled at, insulted, threatened, hit, or strangled — while enrolled at the College did not change significantly between the 2017-18 survey (when these questions were first introduced) and the 2020-21 survey.

The Sexual Assault and Prevention (SAPR) Office declined to provide data on faculty and staff harassment of students to the Record as of yet, citing a need to speak with the Dean of the Faculty’s office first.

Changes to campus culture and student attitudes

According to Bossong, the data on the prevalence of sexual violence is just “one snapshot of people’s experiences at Williams,” with the questions on campus culture and climate serving as supplements to understanding students’ experiences.

In a question asking students how often they hear or see (via messaging or online posts) members of the Williams community “say that a test, assignment, or other activity ‘raped’ them,” the proportion of students who responded “never” increased steeply from 32 percent in 2014-15 to 53.8 percent in 2017-18 to 72.7 percent this year. The proportion of students who heard or saw this “often” dropped from 6 percent to 1.6 percent over the same time period.

Similarly, the percentage of students who reported hearing jokes about assault or rape “often” fell dramatically from 15.5 percent in 2014-15 to 2.6 percent in 2017-18 and 0.7 percent this year.

Students’ conceptions of consent have also evolved over the last seven years. In the 2014-15 survey, 15.2 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that “if a person initiates kissing or touching, they have consented to sex.” This year, only 1.5 percent of students indicated any level of agreement.

“These are pretty massive cultural shifts that you can see taking place in people’s experiences,” Bossong said. “That is not solely attributable to [Assistant Director for Violence Prevention Hannah Lipstein] and I, but the culture is shifting.”

“I do think that is heartening in ways that are good to remember,” Bossong continued. “It makes it feel like it’s important that we keep putting our shoulder into this push because it is changing things, and people who are here today are having a qualitatively different life experience around these issues than people who were here in 2014-15, and that matters.”

Students’ attitudes towards other statements regarding consent have remained more constant over time. These statements included: “Consent must be given at each step in a sexual encounter,” which 94 percent of respondents agreed with this year; “If someone invites you to their room, they are giving consent for sex,” which 98 percent of respondents disagreed with this year; and “It is not necessary to discuss consent before sexual activity if you are in an ongoing relationship with the other person,” which 82 percent of respondents disagreed with this year.

Using EPHCASA data to inform response and prevention programs

Bossong said the last time students were directly involved in creating the survey was in 2017. Though students did not have a hand in writing the survey this year, student groups such as the Rape and Sexual Assault Network (RASAN) and Masculinity, Accountability, Sexual Violence, and Consent (MASC) continue to engage with Bossong’s office in a number ways.

Laura Westphal ’21 is a co-chair of RASAN and first began working with Bossong through the organization. “I knew of the SAPR office because they do consent and bystander training with all of the varsity athletic teams,” said Westphal, who is a member of the women’s swim and dive team. “But when I became involved with their office, it was definitely through RASAN.”

Westphal said that RASAN helps the SAPR office with programming such as the “Speak About It” skit presented to first-years during First Days, as well as campaigns promoting consent and safety in party spaces on campus.

According to Bossong, the College uses the EPHCASA survey data to improve its support systems and prevention programs. “For example, questions about bystander interventions, we take that data, and we use it to design scenarios that are pretty individualized to the groups that we’re doing bystander intervention training for,” Bossong said.

“Another way that we use the data is taking the consent beliefs that people have and feeding that into consent workshops that we’re doing, making sure that we have scenarios that are addressing some of the underlying attitudes that are coming up there,” Bossong continued.

The survey also asked students to indicate how they expect the College to handle a report of sexual misconduct. Respondents were asked to rate a list of actions by the College as “very unlikely or unlikely,” “neutral,” or “likely or very likely.” In 2014-15, 80.8 percent said it was likely or very likely that Williams would take the report seriously. That percentage fell to 54.5 in this year’s survey.

However, the proportion of respondents who said it was likely or very likely that Williams would support the person making the report increased very slightly from 72 percent to 73.1 percent over the same period, with a dip to 63.3 percent in the 2017-18 survey.

Last August, the U.S. Department of Education implemented changes to Title IX regulations that narrowed the definition of sexual assault and strengthened the rights of the accused. When the changes were first announced in May 2020, some survivors’ rights groups argued that the new regulations would discourage survivors from reporting sexual misconduct.

According to Bossong, there is no way of telling whether the quantitative data from this year’s EPHCASA survey was affected by the changes to Title IX regulations. She noted, however, that the College has not received any formal complaints (in which a person brings a complaint to the Title IX coordinator and seeks investigation) since the policy went into effect last August.

“In that sense, the Trump/DeVos Department of Education officials have achieved their goal of fewer students being adjudicated by their institutions,” Bossong said. “It is vital that we continue talking about both supportive accommodations so people can live safely on campus and continue to access their education as well as prevention.”

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

In a series of nine questions asking students what actions they had taken as bystanders, the proportion of respondents who said they had done so decreased across the board in this year’s survey, likely due in part to the effects of COVID-19 restrictions, Bossong said.

The percentage of students who said they had “checked in with a friend who looked very intoxicated when they were leaving a party with someone” fell from 64.5 percent in 2017-18 to 49.8 percent (although this is still higher than the 32.1 percent from 2014-15).

Decreases were also reported in questions about talking about sexual violence, expressing discomfort about rape jokes, interrupting conversations where one person seemed to be making another uncomfortable, and calling CSS or the local police to intervene in a potentially unsafe situation.

Bossong said that this steep drop in the percentage of students who said they had engaged in bystander interventions was one area where the pandemic seemed to have affected campus. “That’s where we can see the impact of people spending much less time in person with other people,” Bossong said. “More than half the respondents to this survey are first-years and sophomores, who have had pretty atomized experiences on campus in terms of the number of people they’ve gotten a chance to form relationships with.”

Bossong also said that the College has done fewer bystander workshops this year, focusing instead on articulating consent as it relates to COVID. “Our content, in terms of our prevention work, has really pivoted from one that addresses a campus that is constantly changing the configurations of its social spaces at any given time to one that’s much more focused on people spending time with a small group of people that they have very tight relationships with,” she said.

Lipstein noted how COVID has decreased community connection among people, as well as decreasing access to resources. “Isolation is one factor in particular that can really escalate risk levels,” she said. The pandemic has also increased concerns about family violence and domestic violence, Lipstein said.

She expressed concern about how the isolation factor, as well as many students being off campus, affects the way the College can reach out to students. “We’ve just seen more people who are dropping off the radar, and then all of the resources that usually exist to reach students — none of us were able to get through in the same way,” Lipstein said.

Students’ level of comfort with seeking resources has also changed as a result of public health restrictions on social interactions, according to Bossong. She noted that many students who began relationships during the pandemic might have been violating COVID rules if their partner was not in their pod. “It can make it very hard to talk to your friends or think about seeking resources [in the event that sexual or dating violence occurs],” she said. “It’s just creating a lot of fear and a lot of trepidation for people to talk about their experiences.”

Bossong emphasized that her office has a confidentiality policy, as well as an amnesty policy regarding COVID rules, but students might nevertheless feel uncomfortable discussing sexual violence when that means disclosing rule-breaking. “I actually think that what our office is preparing for is a lot of conversation, perhaps in the fall, when things feel less risky around COVID,” she said. “We’re preparing for delayed conversations about people’s experiences this past year.”

Preparing for the future

“When I look at the bystander data, what that tells me … is we have a lot of work to do as we reconnect as a community,” Bossong said. “Learning how to be together again is going to need to be a really intentional thing that we bring some practice to.”

Westphal took note of the ways in which the pandemic has changed people’s attitudes towards consent in particular, as new social norms regarding mask-wearing and social distancing, have created the need for explicit communication.

“People are generally more understanding and willing to talk about consent, because it can apply to COVID and not just intimate partner violence,” Westphal said. “Sometimes, when we bring up discussions of consent, people are very reluctant to talk about it. I think having masks on and needing to — at least among my friends, if they’re not in my pod — we still ask each other, ‘Can I take my mask off now?’ or ‘Can I give you a hug?’”

“The pandemic has increased our need to ask for explicit consent and have those conversations, which I think is really important and definitely applies to our work in intimate partner violence,” Westphal continued.

Westphal expressed hope that people’s awareness of consent has improved over time, based on her own experience with campus culture. “I would even say the difference between my freshman and junior year, I could track between my own entry and the frosh,” she said. As a Junior Advisor last year, Westphal said several of her first-years had programming similar to “Speak About It” and RASAN in their high schools. “I think that was a really good sign that … there are more conversations about consent, sexual well-being, and relationship dynamics that are happening,” she added.

The fact that the prevalence rate of sexual violence on campus is lower than the national average might also signal a positive change, but Bossong cautioned against treating it as a victory.

“On the one hand, that gives us the opportunity to say, ‘Are we doing something differently than other colleges and universities that makes that possible? And is there something that we could share with other institutions so that they could try to replicate that lower level of prevalence?’” Bossong said. “But it is challenging to think about celebrating that lower level of prevalence, because for people who have experienced violence here, there is no difference between their experience and that of the national data.”

“We know that people do have experiences of harm here at Williams, whether that is captured in surveys or not,” Lipstein said. “We know that there is still work to be done.”

Lucy Walker contributed reporting.

If you would like support relating to sexual assault or intimate partner violence, please contact one of the following 24-hour resources, as listed in the EPHCASA survey:

- Sexual Assault Survivor Services at Williams 413-597-3000

- Elizabeth Freeman Center 866-401-2425

- RASAN 24×7 Peer Support 413-597-4100