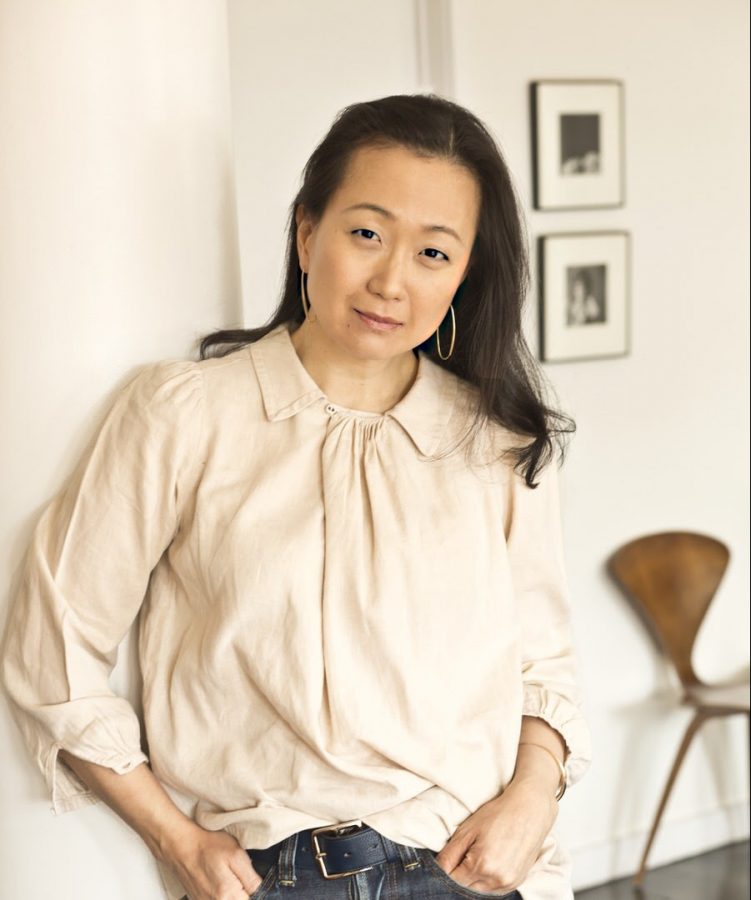

‘Maybe you and I can share a little bit of a world together’: Min Jin Lee on creating her world

May 19, 2021

The summer before my senior year, I picked up National Book Award finalist Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, a 500-page epic tracing four generations of a Korean family through time and space, and discovered that I could not put it back down again. Attending an intensive creative writing summer camp at the time, I devoured the carefully constructed narrative in between classes, activities, and assignments, savoring every chapter like it was a heartwarming bite of the protagonist Sunja’s homemade kimchi.

Looking back, I cannot begin to separate my writing that summer from my experience reading Pachinko. The mark that both Pachinko and Lee’s debut novel Free Food for Millionaires have left on my relationship to storytelling runs bone-deep. So when I answered a call from an unknown number on May 6, my stomach was a knotted mess of nerves and excitement as Lee’s voice sounded from the speakers.

My interview with Lee came just minutes after she joined Chair of Asian Studies and Professor of Political Science Sam Crane for a conversation and audience Q&A. Throughout the night, Lee spoke with great deliberation and good-natured humor about her relationship to activism, her approach to writing, and her take on the value and commodification of art.

Lee began her conversation with Crane by reading “Breaking My Own Silence,” an essay on her belief in the power of speech published in The New York Times.

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Lee migrated to Elmhurst, Queens in New York City when she was 7. At that time, neither she nor her two sisters were able to speak English. She would spend the next couple decades learning the art of speech, still learning even as she graduated from Yale College and enrolled at Georgetown Law.

Lee later elaborated in conversation with Crane that the moment she first connected language and power was in a much more personal setting than the classroom. When Lee was in high school, The Korea Times, the oldest English-language daily publication in South Korea, solicited and published a short essay she wrote about being unable to speak Korean. Her father cut the article out of the newspaper and pasted the clipping up on the wall of his cramped jewelry store.

“I do remember … thinking, ‘Oh, my father’s paying attention to what I’m doing. That’s kind of wild,’” Lee said. “It wasn’t that he wasn’t paying attention, but he thought it was important because this media outlet thought it was important, and I think he was proud of me.”

The seeds of thinking of language as power were planted. A few years later, Lee was reminded of this idea during a nearly empty lecture about the ongoing discrimination against ethnic Koreans in Japan. “I was so shaken by what I heard in this talk that I couldn’t quite figure out: What am I going to do with this knowledge of oppression?” Lee said.

According to Lee, she hadn’t even planned to attend the lecture in the first place. She only agreed to go because she was unable to say no to the person who invited her. Though she was one of only two students in attendance, this accidental moment in her college experience laid the foundation for Pachinko.

“I didn’t know what to do with this story of hate, and … when I think about today, when I think about all these hate incidents against Asians and Asian Americans — it’s so horrible because they’re so completely the same,” Lee said. “My sense of outrage is triggered again and again and again right now… I wrote this book as an act of activism.

Racism was not the only structure of power that Lee addressed in Pachinko. She also explored other themes of resistance and survival through a lens of gender. “The people who are enforcing systems of power against other groups that have less power are often people who aren’t that powerful,” she said. “That’s what’s interesting — it’s not like you have the king saying, ‘Don’t do this.’ Very often, it’s your father-in-law who says, ‘Don’t do this.’”

To illustrate her point, Lee pointed to the character of Yoseb, Sunja’s stubborn brother-in-law who attempts to enforce patriarchal gender roles — such as the male breadwinner and the domestic female — despite the family’s dire financial situation. Yet, for Lee, these values do not necessarily make Yoseb an evil person.

“I think he really, really meant well, and if he believed in the values of patriarchy, he was just a product of his time,” Lee said. “Very often, we take our values of the 21st century and impose it on people from the 19th century or the 20th century, and I think in some way, it’s not fair.”

For Lee, when dealing with such sensitive and complex issues, it was important to be sympathetic — beyond that, it was important to tell the stories of real people. In fact, Pachinko did not begin as a work of fiction, but rather as a project of academic scholarship.

“Essentially, it is an epic saga, it is a historical novel, and that’s where you would put it in terms of a literary understanding,” she said. “But it’s also a book that encompasses a lot of disciplinary field[s]: It’s got history, economics, law, anthropology, sociology, and that’s very intentional — I looked at those fields first before thinking about fiction.”

In an interview with Writer’s Digest, Lee spoke about her unique (or “really weird,” as she would later describe it as to me) writing process, which includes formulating broad questions about a topic and then conducting hundreds of interviews. As an aspiring writer and journalist myself, I was fascinated by the journalistic style of her research, which, according to Lee, was important for the development of her narrative omniscient voice.

“One of the things that I really like to convey is how much I love people and how much I accept people, and that’s a very important thing because I write in the omniscient voice,” she told me. “So there is a narrator who knows beginning, middle, and an end and can read minds. Like — that is me; I’m actually the omniscient narrator, which means that I must love all of my characters. So when I interview people, I try very hard to accept people for who they are.”

In order to accept both her characters and the people they are based upon, Lee told me that she must fully understand the essence of her interviewees. “Who you are versus who you wish you [were] are different people sometimes — for the most of us,” she elaborated. “So I try to see both people, and then I try to see all the people behind them. And by that, I mean I try to understand your parents, your ancestors, your siblings, your regional identification, and that helps me to kind of get a 360 overview of you.”

In the process of constructing the lives of the everyday people of history, Lee would read and listen to various stories of pain, fear, and suffering. Her research included topics such as war crimes and the Japanese occupation of Korea. At times, she said, this work became depressing.

“I had to stop because I couldn’t take it, and then I had to focus on something else,” Lee said. “So you have to go deep, but you can’t go so deep that you can’t recover because we’re human. And part of my gift is empathy, … and I used to think when I was a kid, ‘That’s weird, and there’s something wrong with me because why do I feel so much?’ But now I realize that, ‘Oh, no, actually it’s my superpower.’ But because I can do it, and I do do it so much, I have to be careful how I use my powers because I can get really depressed. I can get really anxious. I can get really troubled.”

In the face of feeling overwhelmed with negative emotion, Lee said that the most important thing to do is to rest and to be honest. However, she harbored an intense dislike of the phrase “self-care.”

“I think the intention behind self-care is probably incredibly important and moving and beautiful and helpful,” Lee said. “We take this notion of preserving oneself from the ravages of a neoliberal capitalist system, because that’s what it really comes down to.… But will bubble baths and pedicures and pictures of cats save us? No, I don’t think so.”

Another sentiment that Lee said she struggled with upon the publication of her novels related to the paradox of art as a commodity. “I find now the exploitation of my ideas to be deeply distressing,” she said. “That’s weird when the thing that I created out of love is seen as a commodity. That’s weird to me because I never intended that to be a commodity. It is obviously a commodity, but that’s not how I began it.”

According to Lee, what is even more important to her than the royalties she receives is the time that readers invest into her novels. “People think, ‘Oh, you wrote this book for money.’ I mean, I gotta tell you, that is a joke because when I sell a novel, I make about $1.12,” she said. “But what I do get, if you finished my novel, is — I got 16 to 18 hours of your time and attention. I got you to think about things that were really important to me, and maybe they’re important to you, and maybe you and I can share a little bit of a world together.”

The advice Lee would give to aspiring writers is intrinsically linked to how she values her own writing. “The most important thing is reading and then writing,” she said, pointing to articles she has written over the years about this same topic. “But writing without reading makes no sense… I have read so much writing; I have done so much judging, and I’ve never seen a great writer who doesn’t read. So whatever your background is [it’s important] to read widely, to read deeply, to be thoughtful about reading, and also to keep writing terrible things, … stuff that makes you embarrassed. And most importantly, ask yourself what you want to say.”

At the end of our talk, Lee told me that it was her pleasure to speak with me. And then she thanked me. Days later, I hope that she understood when I rushed to correct her — that it was, in fact, my pleasure to have the opportunity to speak with her, an Asian American novelist who researched like a journalist; wrote unabashedly about real people and real stories; and spoke with compassion, humility, and grace.