To the Class of 2021: Commencement messages from alums

You are now leaving Williamstown

William Finn ’ 74

After I graduated from Williams in 1974, I spent the summer with the second company of the Williamstown Theatre Festival. Marvelous summer. Great friends. Decent theater. After the season was completed, I began the drive back to my hometown outside Boston on Rte. 7, going to the Mass Pike, and passed the “You are now leaving Williamstown” sign. The sense of security and goodwill I’d felt for four years was quickly lifted and I started to sob uncontrollably and had to pull over to the side of the road where I cried for 20 minutes more.

This was not how I had expected to leave Williamstown.

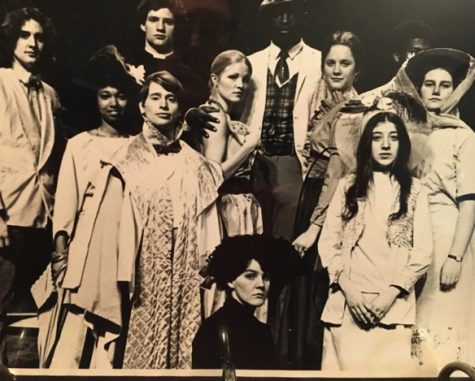

Actors in the musical I wrote and directed during my junior year at the College. (Photo courtesy of William Finn.)

While at Williams, I wrote the music and lyrics for three musicals for the mainstage and directed two of them. I loved reading the novels I read, loved less writing the papers about the novels, but loved being here. I was confused. I learnt, “You must listen to everybody,” but also, “You must listen to no one.” I wanted to do what was right but I wasn’t sure exactly what that was. But I felt I had to fake it, which I did, so I appeared confident and sure, even when I wasn’t. I was confident, but I wasn’t sure about what.

So I stopped writing completely and thought of studying to be a doctor, which was ridiculous. Couldn’t pass a science course to save my life, but I loved being called doctor. A friend of mine was an OB-GYN resident, and I’d put on my blue intern shirt and assist her (not help) between 11 p.m. and 8 a.m. until one day the nurses asked me to draw blood. So I left the hospital and called my friend and told her to go draw blood in room something-or-other and said goodbye to medicine forever.

Here I was, a writer who wasn’t writing who called himself a writer. So I invited the best singers over, and I’d write them little songs. We’d rehearse. I’d cook chicken wings for dinner (the cheapest protein) and we’d sing. Eventually I started writing a show called In Trousers for three women and myself. We performed it many times in my living room with chairs borrowed from the synagogue across the street, and eventually opened at Playwrights Horizons at 42nd St. — first in a small black box theatre, then the larger main stage. Playwrights Horizons commissioned me to write another show, which became March of the Falsettos, and then commissioned me to write something else, which became Falsettoland. Together they turned out to be Falsettos, for which I won Best Music and Lyrics at the Tonys and many other awards.

The road, however, was not smooth. Although it only took seven years to get from leaving Williamstown to Falsettos on Broadway, I felt I’d been wandering in the desert for decades. Don’t expect a road without mistakes. My God, the errors I made — and the humiliations I suffered, the blunders, missteps, unintentional sidetracks — were there for a reason, I guess. I hope.

Here’s my advice: Say “no” as infrequently as possible and say “yes” even when life seems its bleakest. As you leave Williamstown on your way to wherever, I’ll be hiding behind the “You are now leaving Williamstown” sign with a box of tissues. Honk.

William Finn ’74 is a composer and lyricist. He lives in New York, N.Y.

Feeling your way forward

Sean Saifa Wall ’ 01

Twenty years ago, I too graduated from Williams College. Similar to now, I graduated during one of the most challenging times in the U.S. economy, when the infamous tech bubble burst in Silicon Valley and sent a wave of despair and economic insecurity through the nation. Whereas the previous year Williams was courted by Wall Street giants like Bears and Stearn, Goldman Sachs, and the Lehman Brothers (to name a few), the number of companies that were hiring the Class of 2001 dwindled and the competition was fierce. I applied for a position at a consulting firm at which I failed miserably, and my dreams of living the high life went into the bin. Unlike some of my classmates who would venture on to graduate school, return home to live with parents as they figured things out, or work for one of the big Wall Street firms, I accepted an internship at the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR).

I was scared because I took an unconventional path in an uncertain economy. With few prospects, I was fortunate to land the FOR internship which included a stipend and housing. Unbeknownst to me, FOR was one of the oldest peace and justice organizations in the country that cultivated leaders such as Bayard Rustin, who would later be considered one of the architects of the March on Washington in 1963. During this internship, I read books such as the autobiography of Assata Shakur, a former Black Panther living in exile in Cuba whose message echoes in the protests of Black Lives Matter: “We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

At FOR, I cultivated a deeper understanding of social justice which was an extension of the activism that I was engaged in at Williams. Since FOR, I have tirelessly advocated for justice and equity, joining movements that encompass anti-militarization and queer and transgender justice. Now, I work as a leader in the movement towards intersex justice.

I didn’t know where this life would take me, but in hindsight, I now know that it is one day at a time and one foot in front of the other. In addition to being an intersex activist and rising scholar, I am a somatic practitioner that works with people to address trauma in the body. I believe that the body is a powerful tool to understand your emotionality, especially in environments where emotional intelligence is not held with care or valued.

When I work with people, one of the questions that I ask is, “What do you want your legacy to be?” To the graduating class of 2021, I encourage you to lead with love and conviction. I think we are often influenced by our peers and sometimes our parents who push us into a certain career path that may not be for us. But this begs the question, what do YOU yearn for? In this moment of profound loss and grief, we are forced to reckon with what really matters now that we are acutely aware of the veil between life and death.

In closing, I leave you with a few adages that I have picked up along the way which are guideposts in both my personal and professional life. As you venture into the world, I hope that these resonate for you as they have for me.

1. Acknowledge what has hurt you: Unfortunately as humans, we will hurt each other sometimes in ways that are truly profound. “I am sorry” goes a long way in healing the hurt that has been caused. However, the path to healing is acknowledging the ways in which you have been harmed. Your story may give someone else the courage to speak out.

2. What is for you, won’t miss you: I have applied to many jobs, fellowships, and grants where I was rejected, and the ones that I did receive confirmed where I was supposed to be. Our personalities may not resonate with every environment so even though it hurts to feel the pang of rejection, just know that when one door closes, another one opens.

3. Other people’s urgency is not your emergency: With the growth of social media platforms and services like Amazon, we have created an artificial culture of urgency and demand. As a result, there is increased anxiety that compounds the existing anxiety in our personal lives. Although easier said than done, ask for extensions and try to stay connected to your own timeline of production.

4. Sometimes our willingness is ahead of our readiness: I learned this one from 12-step recovery. Remember the expressions “good things take time” or “haste makes waste”? Allowing yourself space to absorb information at your own speed is compassionate even though you may be really excited about someone or something.

5. The world does not benefit from you hiding your gifts: If you are a writer, write! If you long to make music, compose! Life is too short to suffer in a profession where you don’t feel moved or inspired. The world deserves your talents.

Sean Saifa Wall ’01 is an activist for intersex rights. He lives in Manchester, England.