Students celebrate a second pandemic-era Passover

April 7, 2021

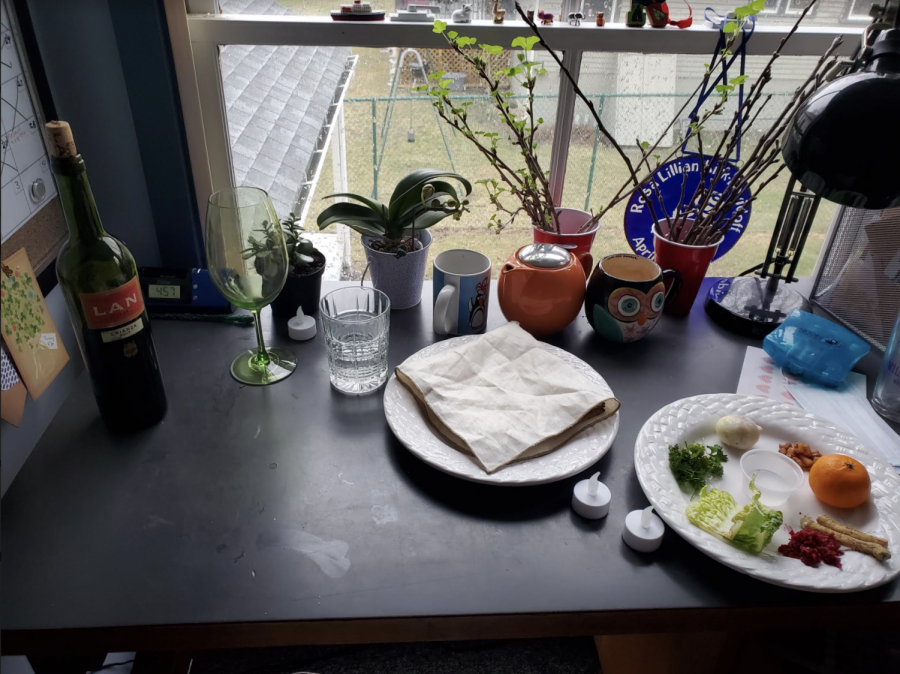

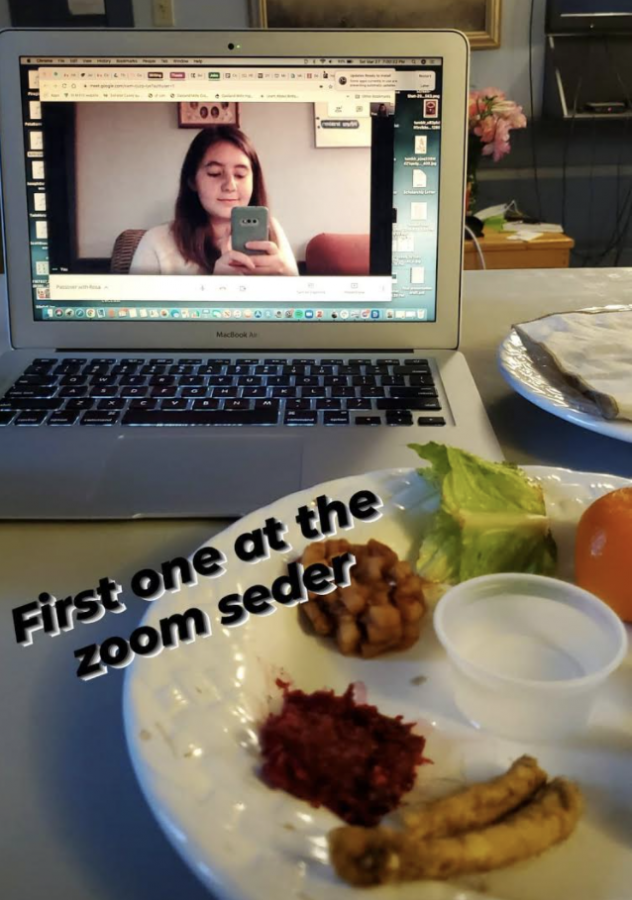

This year, the Jewish holiday of Passover (known in Hebrew as Pesach) began on the evening of Saturday, March 27 and lasted until the evening of Sunday, April 4. Although it was not the first time Passover traditions had to be modified in response to the global pandemic, students celebrating at the College faced unique challenges in observing the occasion and accessing food in accordance with religious dietary needs. Hosting online Zoom seders and performing a play in a socially distanced gathering were among some of the creative ways students found to uphold their traditions in compliance with the College’s COVID regulations.

‘It’s great to be able to bring together everyone’s experiences and traditions from home’

At the center of Passover traditions are the seders, ritual feasts that commence the holiday and usually include the recitation of a Haggadah — a Jewish text that has many adaptations for different sects of Judaism and includes the story of Exodus.

Despite being unable to meet in person this year, Noah Jacobson ’22, Rebecca Coyne ’22, and Regina Fink ’22.5 organized and hosted virtual seders during the first two days of Passover. “Seders are just so much fun,” Jacobson said. “It’s especially difficult to do them remotely, but I’m glad we were able to put them on this year.”

“It’s great to be able to bring together everyone’s experiences and traditions from home and kind of create a new Jewish community here,” Coyne agreed. “We had Solly [Kasab ’21] do a musical performance of the story to the tune of a song from The Music Man.”

Fink said that while she would have loved to meet in person, she was still grateful for the opportunity to congregate online. “It was so nice to see everyone’s face on Zoom, and one person emailed me after and it meant so much,” she said.

Other students opted instead to meet safely in person, among them Rebecca Tauber ’21, Eddie Wolfson ’23, and their friends, who held a small socially distanced gathering outside to celebrate. “We actually adapted my family’s script into [a play],” Wolfson said. “We added some Williams-relevant jokes in there, [and it was] theatre-in-the-round-esque.”

‘When our ancestors left Egypt, the bread didn’t have time to rise’

Another Passover tradition is the prohibition of possessing and consuming chametz — foods with leavening agents. In some communities, the prohibition also includes kitniyot, a Hebrew word for “legumes” that often encompasses grains and seeds like corn and rice.

“Someone was asking me, ‘Oh, why can you only eat matzah?’” Rosa Kirk-Davidoff ’21 said. “I’m like, ‘It’s because when our ancestors left Egypt, the bread didn’t have time to rise.’”

Due to the College’s COVID restrictions, students were not permitted to use the kitchen in the Jewish Religious Center (JRC). Instead, they had the option of ordering catered microwaveable meals for each day of Passover for pick-up at the JRC.

“I think food was definitely a challenge this year, more so [than in previous years],” Tauber said. “Usually at Williams, [keeping kosher for Passover] is pretty fun because they have the JRC kitchen open and it’s fully stocked… People will go there to make themselves meals, and it’s very much [a] nice community.”

Fink, like many other students who celebrated, ordered the catered meals. “I thought I was going to be a lot more okay because I really thought the corridor was gonna open, and we were gonna get to go,” she said. “So I didn’t really plan ahead.”

Jacobson explained that he benefited from living closer to the College than most students, allowing him to plan ahead. “I brought an entire box just with Passover food, snacks, and jars of jelly to put on my matzah,” he said. “Not everyone can do that because a lot of people fly in or take a train or a bus or something.”

‘We’re doing some of the same rituals that people have been doing for a thousand years’

Just as the traditions of Passover vary among different communities and individuals, so do its meanings.

“To me, Passover is a time to spend with family and friends,” Jacobson said. “But at its core, it is a holiday that celebrates not just the freedom from the Egyptians, but also wandering in the desert for forty years and then getting the Torah and the Ten Commandments.”

“We’re doing some of the same rituals that people have been doing for a thousand years, and I think Passover really connects you back to that aspect of it,” Kirk-Davidoff added.

Fink connected her observance of Passover with issues of social and environmental justice. “We as Western Jews living in the U.S. should be more cognizant of our role as consumers of the Global South’s products,” she said. “Even us college students, just constantly consuming dining hall food and these [other] incredible resources.”

“The adaptation of those sort of lessons of freedom and solidarity to social justice issues that currently affect our world is also something that’s been really meaningful to me,” Coyne said.