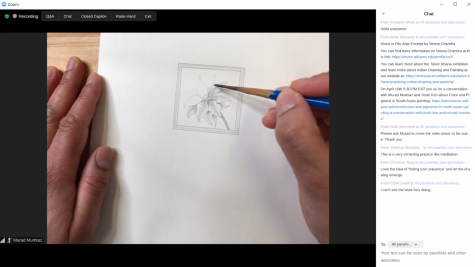

Professor Murad Mumtaz teaches on the art of miniature painting

March 31, 2021

On March 11, Curator of Mellon Academic Programs Elizabeth Gallerani, art history graduate student Amber Orosco, and artist and Assistant Professor of Art Murad Khan Mumtaz hosted an event titled “Practice & Process in Indian Drawing,” during which attendees were able to take a deeper dive into Indian art and, more specifically, Indian miniature painting.

The workshop began with a brief introduction of Tasvir Khana, a Persian term referring to the workplace in which Indian miniature paintings are created, and its significance to the past and contemporary art sphere in India. When discussing the medium, Mumtaz emphasized the importance of outlines and learning how to create “minute, controlled, and refined lines.” After all, as Mumtaz elaborated, “if you look at any traditional Indian painting, everything is bound or contained in a beautiful outline.”

After the outline has been created, the paint is applied. Many of the materials used to create the paintings are organic; for instance, the paints used are often natural pigments bound with gum arabic or animal bone glue, often placed in seashells as a holder, and paired with squirrel tail brushes.

According to Mumtaz, a squirrel tail brush is used for the main detail work, since it has a “perfect point at the tip, and yet it is thick on the bottom so it can take in a lot of pigment and water… [meaning] you can run it for a long time while making an extremely minute and refined line.” However, working with such brushes “may take months and months to get used to,” and Mumtaz recommended a sharpened 4-H or 5-H pencil on paper as a way to learn and practice the techniques.

To provide visual insight into the intricacies of Indian miniature painting, participants were also able to observe two drawings: A Tall Flower with Pink Blossoms and Raja with Attendant, both from the Indian art collection at the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA). After brief introductions to the pieces by Gallerani, Orosco also mentioned the use of a technological software known as Reflectance Transformation Imaging, which allows viewers to manipulate the light and surface shape of a subject. Orosco demonstrated this application on the former illustration, which helped to “isolate the linear qualities of the painting” and add depth to make the two-dimensional surface appear three-dimensional.

To provide visual insight into the intricacies of Indian miniature painting, participants were also able to observe two drawings: A Tall Flower with Pink Blossoms and Raja with Attendant, both from the Indian art collection at the Williams College Museum of Art (WCMA). After brief introductions to the pieces by Gallerani, Orosco also mentioned the use of a technological software known as Reflectance Transformation Imaging, which allows viewers to manipulate the light and surface shape of a subject. Orosco demonstrated this application on the former illustration, which helped to “isolate the linear qualities of the painting” and add depth to make the two-dimensional surface appear three-dimensional.

Throughout the workshop, Mumtaz gradually introduced and built upon the concepts present in miniature painting. “Indian painting uses multiple perspectives … in which you show the thing that is most important, most clearly,” Mumtaz explained. “It is about showing [what] is necessary to the narrative and not about following the accidentality of nature because that is just an illusion created by our eyes.”,”

Upon being asked about the potential issue of cultural appropriation, Mumtaz said that the art of miniature painting has always been an accessible and open one.“I would say none because this is a practice that has always been open to learning from other traditions,” he said. “It is a practice that has never been hermetically sealed, which is why it is still today a living, breathing contemporary practice.”

“This practice has always been taking and giving,” he continued. “Anyone should and can experiment with this [or] use it in their own practices, knowing that it has always been an art practice that has looked towards global networks.”