Professor of Art Mike Glier answers with abstraction

March 10, 2021

As the lecture began, I was worried about my wifi connection, which had been phasing in and out for the whole week. Thankfully, things worked out. On March 4, Professor of Art Mike Glier presented “Answer Music: Observation and Abstraction of the Living World,” the second Zoom webinar in the College’s annual Faculty Lecture Series.

Glier’s slide talk focused on three of his recent bodies of work: The Forests of Antarctica, Field Notes, and Answer Music. The three are linked by their subject matter tracking the human relationship with the environment, and by the use of abstraction. “Encouraged by the unexpected results of drawing something that is invisible but can be felt, I began to draw not only what I could see, but also what I could feel on my skin and what I could hear and what I could smell,” Glier said.

The Forests of Antarctica

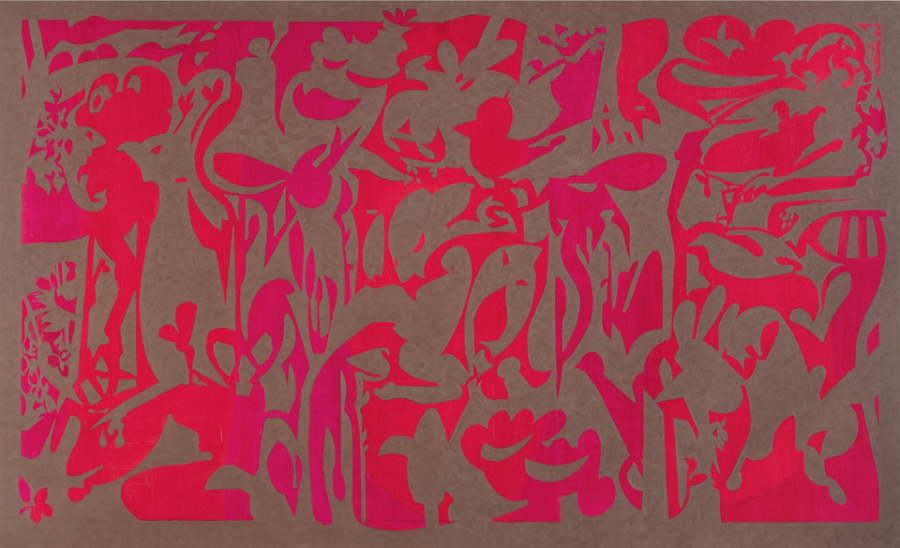

Though a series of paintings, the sharp contours and flattened shapes of The Forests of Antarctica reminded me of paper, like Kara Walker’s famous silhouettes or even traditional Chinese paper cutting. However, the degree of abstraction here is a significant point of departure from those techniques. For one, Glier’s paintings emphasize positive and negative reversals.

“Sometimes the image is black, and sometimes the image is white, and they flip back and forth,” Glier said during the webinar.

I could see a bird here, a branch there — forms blended together, and the visual experience was like a Rorschach Test. And crucially, many forms in these paintings are “associative” rather than directly naturalistic depictions, Glier said. For example, in The Forests of Antarctica #159, a group of upwardly curving marks visually resemble “clouds and smiles,” according to Glier, but represent the sound of a gurgling river.

The impressive size of these paintings makes for a somatic experience that was somewhat lost over Zoom. Fortunately, Lake Bascom, another work in the series, can be seen in person at the ’62 Center for the Performing Arts. While working on the painting, Glier found it important to incorporate the colors of the ’62 Center, the purple of Williamstown’s mountains, and the character of the theater and dance departments.

“The place always provides guidance,” Glier said during the webinar. “The mural had to not only work with the architecture and reference the landscape in which we live, but also engage with the exuberant programming of the theatre and dance departments. To this end, the design is full of curves and nothing is settled. There’s no single focus to this picture. There’s no star of the show. This is definitely an ensemble production of improvisational theater. It’s all about movement, vitality, and a bit of drama.”

Field Notes

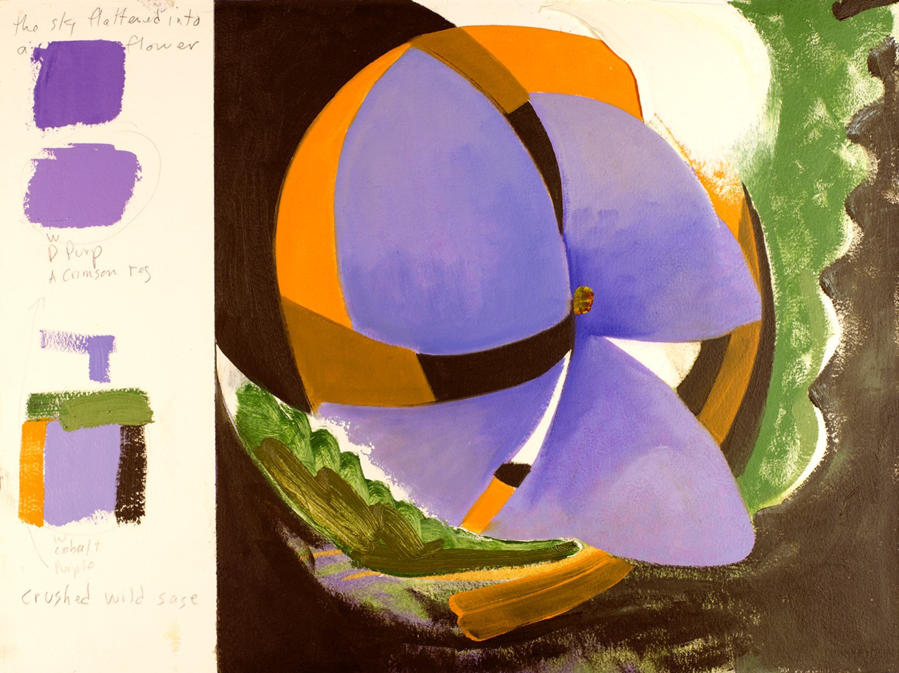

Unlike the amalgamation of forms that characterized The Forests of Antarctica, each of Glier’s Field Notes centers around a single moment in nature, such as seeing two seals ride the tide or hearing the growl of a bear. Listening to Glier’s narration of these much smaller paintings felt like reading a collection of haiku, as many were accompanied by short, poetic texts: “The building clouds looked like a brain,” or “The sky flattened into a flower.”

Glier paused between each work, creating moments of stillness that were long enough to provide space for contemplation and short enough to create a continuous experience that strung multiple works together. In this series, too, abstraction is on display. For example, one work reimagines a flock of bleating sheep as “crying beasts” (I thought of Om Nom from the Cut the Rope), and another synesthetically depicts the sound of dogs barking.

Answer Music

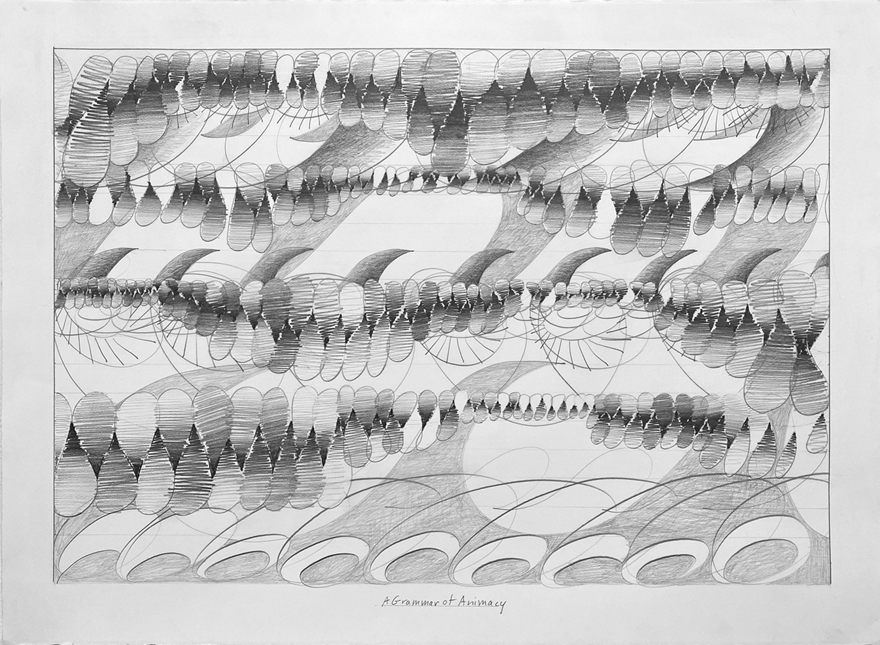

Last summer, Glier began the Answer Music series. The title refers to call-and-response worship in churches; for Glier, the call is the sound of a river or a chorus of birdsong, and the response is the art that it inspires. To my eye, this series of drawings was the most abstract. The drawings are largely composed of repetitive, rhythmic motifs that proceed horizontally like a music score.

A guiding concept for Answer Music is Robin Wall Kimmerer’s theory of a grammar of animacy, which describes languages such as Potawatomi that have fewer descriptive nouns and more verbs to capture “the ceaseless exchange of all things,” Glier said. In Answer Music, Glier found it important to identify abstract motifs and rhythms that depict “not the things, but the dynamic relationship between things.”

New work, recurring environmentalism

The lecture concluded with a preview of Glier’s new series, Bird Songs of the Boston Public Gardens, which will be exhibited at the Krakow Witkin Gallery in Boston later this month. These paintings depict sunny, naturalistically rendered scenes from Boston Public Garden alongside abstractions that visually represent the sound of bird songs. The pitch, volume, and timbre of the songs are depicted through the variation of the height, size, and shape of the abstractions.

The human figures visible in Bird Songs are small and lonely, and in a way that reminds me of Edward Hopper’s work, they refuse to dominate the space they appear in — they are merely one part of things. There is an environmentalist motivation behind this artistic decision, and it helps drive Glier’s interest in landscape. In Glier’s view, there is an urgent need to “decenter the human image” by paying more attention to other living things. The artist can play a central role in this mission; by shifting the camera away from humanity itself and turning it toward all that humanity’s actions risk destroying, the artist can get an audience thinking about what needs to be done to protect the environment.

Glier said he recognizes that painting is not often a form of mass media that maximizes the proliferation of a message — he sees design and digital arts as more promising fields for that purpose. Instead, like poetry, painting is a more “intimate” art form that can strike a smaller audience at an emotional level.

“Every effort counts. If you influence ten people, you change ten people’s thinking lives, that’s okay, that’s important,” Glier said. “Not all of us have to be thinking of scale all the time.”