Students adapt Lunar New Year celebrations for travel, quarantine

February 17, 2021

Topjor Tsultrim ’22 celebrated Losar, the Tibetan New Year, from the United Kingdom, where he is studying at the Williams Exeter Programme at Oxford. Losar, which falls on the first day of the lunisolar Tibetan calendar, coincided this year with the Lunar New Year.

“Losar is our biggest holiday,” Tsultrim said. “It’s your birthday and Christmas and New Year’s all wrapped into one. Everyone gets dressed up in our traditional clothing, and you have all these traditional foods and prayer services.”

As a member of the Tibetan community, Tsultrim explained the significance that Losar holds for the culture and identity of Tibetans. “We are able to come together as a community and reaffirm and reclaim our culture,” he said. “It’s really a day for us to — no matter where we are — try to reconnect with our Tibetan heritage.”

Many other cultures that follow lunar or lunisolar calendars celebrate the beginning of the calendar year in similar ways. The Lunar New Year, which starts February 12th and can last for several days, is celebrated in Tibet, China, Vietnam, Taiwan, and more.

However, as most students prepared to return to campus, many of those who celebrate the Lunar New Year had to explore how they could observe the holiday while adhering to the College’s public health guidelines. Those who chose to return to campus after celebrating the New Year at home, as well as remote students, reckoned with the potential dangers of gathering in large groups, while those already on campus discovered innovative ways to preserve tradition while in quarantine.

‘Celebrating something ancient.’

Angela Chen ’23 celebrated the Lunar New Year on campus out of quarantine. “To me, Lunar New Year is kind of the one moment where everybody comes together and just sits down and spends time with one another,” she said.

Chen described unity as being core to her Lunar New Year tradition. “To me, that’s always been the most important bit: that sense of unity, that sense of … celebrating something ancient and something that’s really close to our heritage,” she said.

Chen said that in her hometown of Kaohsiung, Taiwan, it is customary for people to take time off work and celebrate together. “If you visit my town during this time, it’ll actually be super boring because all the shops have shut down, and people are just taking this time to relish in their family and their connections,” she said.

Angela Gui ’24, on the other hand, spent the Lunar New Year at home in New York City. “For people like me who live in big cities, the meaning of the Lunar New Year [has] evolved into this festival for everyone to get together to celebrate,” she said.

Reflecting on her experience as a high school student in the United States, away from her family in China, Gui added that the Lunar New Year has taken on a new importance for her. “Even if me and my family are sometimes far apart from each other — I’m out here in the United States where my family is all the way there in China — we still have that familial link,” she said.

‘The luck won’t work.’

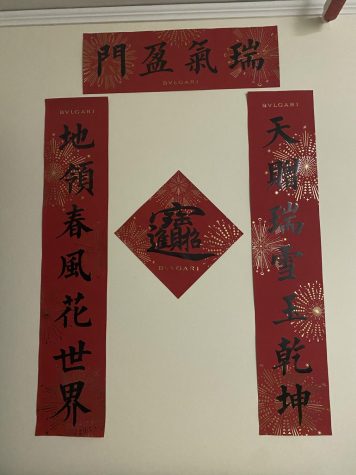

Having returned to campus a few days before the Lunar New Year, Claudia Zhang ’24 had time to make her Lehman dorm room as festive as possible during her initial in-room quarantine. Zhang hung up fai chun, a traditional decoration consisting of golden Chinese characters against red paper, which she received from Bulgari, a luxury jewelry brand, as a gift. “Usually, you’re supposed to put it around the door for good luck and what-not,” she said.

Minh Phan ’23 celebrated the Lunar New Year at her home in Texas. In previous years, her family would traditionally drive to the nearest Buddhist monastery, where they prayed to their ancestors.

“We’ll do offerings and light incense candles,” Phan said. “We wait for those to finish burning and make prayers for good luck, health, and prosperity.” The offerings usually consist of vegetarian food, which comprises the typical Buddhist diet.

Still, despite her relative freedom, Phan said she was concerned about the possibility of contracting COVID-19 during festivities. While the Buddhist monastery still hosted in-person events for the new year, Phan and her family decided to leave immediately after their prayers in order to adhere to social-distancing guidelines instead of participating in group festivities at the monastery.

Tsultrim expressed similar concerns about celebrating Losar responsibly and safely in the United Kingdom. “The U.K. is in a national lockdown, so only essential excursions outside the house are permitted,” he said. “We can’t mix with any other households besides our own.”

To make the most out of his situation, Tsultrim found a way to celebrate from the safety of his own dorm. He attended a Zoom Losar party held by the Tibetan and Himalayan Studies Centre at Oxford, giving him a chance to interact with members of his community during this culturally significant event. “They invited some local U.K. Tibetans to offer songs and poems, and some religious leaders came, and they offered some prayers,” he said.

For Wilson Lam ’22, however, this was not his first socially distanced Lunar New Year. Lam, who is from Hong Kong — where COVID-19 has been prevalent since January 2020 — celebrated at home for the second year in a row with considerably less festivities than usual amid rising COVID cases. “It’s all definitely been very toned-down with the pandemic still going on because public gatherings in Hong Kong are still limited to two people,” Lam said.

Lam said that a negative effect of the pandemic is the restriction of maximum capacity size in wet markets where, in normal circumstances, it is tradition to buy decorations, flowers, food, and branches of pomelo leaves. In Chinese culture, it is believed that showering under pomelo leaves washes away bad luck and bad energy, encouraging deep cleansing before the new year.

Now on campus, Lam continues to celebrate the Lunar New Year. “I’m still in the process of moving in, so there’s not a lot that I can really do to personally commemorate this,” he said. “Because we’re all in this initial phase of quarantine, we’re also limited by that. Really, all I can do is dress in new stuff or dress in red.”

In addition to colorful clothing, Lam also brought back door couplets from Hong Kong. However, instead of the traditional four-character idioms usually written on the couplets, Lam’s couplets are inscribed with popular chants from protests in Hong Kong. “What I currently hold in my hands would be illegal to display in Hong Kong,” he said. “I would be arrested for treason.”

For Lam, these couplets are more than just a temporary decoration; they are also a significant tool through which he can show his support for the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong. “It’s definitely been a thing to incorporate resistance into celebrations just because we have the privilege to be free and celebrating despite the circumstances,” Lam said of the connection between the protests and the Lunar New Year. “We’re trying to keep the spirit of protest alive.”

‘This year, I made my own red envelopes.’

Perhaps the most recognizable tradition of the Lunar New Year is the giving of red envelopes. The giving acknowledges the existence of the recipient, though many cultures that celebrate the Lunar New Year place greater value on giving rather than receiving.

Chen, bored in her room, channeled her festive energy into something productive. “This year, I made my own red envelopes,” she said. “I had red paper in my drawer, and I wanted to make something to give to friends and professors.”

Some families have taken an even greater departure from custom by sending money digitally. “My relatives have been Venmo-ing me a lot,” Phan said.

“[The social media app] WeChat has this red envelope part of it, so you can send red envelopes to a person or send multiple ones in a group chat,” Miranda Wang ’21 explained. “The amount is always negligible, like a dollar split between ten people.”

Although Wang witnessed many red envelope exchanges, she didn’t actually receive any personally this year. “I don’t think [relatives] give them out to college students anymore because you’re making your own money,” she said. “I think there’s some expectation that you hand out red envelopes by the time you get to college.”

‘A fun and interactive, homey way to share our traditions.’

Due to the extended winter break, Loren Tsang ’22 was able to share a Lunar New Year dinner with his parents, brother, brother’s girlfriend, and cousin this year. “We had some fried shrimp balls, curry chicken, [and] fatty pork,” he said.

In a normal year, Gui and her family would come together and make dumplings, among other traditional dishes. This year, however, Gui had to make other plans. “We just ordered out from a Sichuan restaurant downstairs,” Gui said. “Just to get the normal Lunar New Year feeling, we also made braised beef [from scratch].”

In the U.K., Tsultrim cooked his Lunar New Year dinner with friends. “First, we made some khapse, [which] is like a Tibetan biscuit,” he said. “It’s a sweet dough that you deep-fry. Typically, you do that in the weeks leading up to the new year, but I had essays to write, so I didn’t have time for that.”

Along with the khapse, Tsultrim also enjoyed beef dumplings that he made with other students at WEPO. “We all sat around the table, listening to music, making dumplings, steaming them,” he said. “It was nice — a way to celebrate community and give a lot of my friends who haven’t had much exposure to Tibetan New Year in the past a fun and interactive, homey way to share our traditions.”