Harry Yoon ’93, film editor, weaves together the American story in ‘Minari’

February 10, 2021

Harry Yoon ’93, the film editor for “Minari,” wants people to watch the movie with their families.

Having known about the central plot — a Korean American family that, on a gamble, buys farmland, and tries to make it in 1980s Arkansas — I plopped my mom, dad, and sister in front of our TV. And though there are sizable differences between my family’s and the fictional Yis’ migration story, the latter still resonated with us in a way that no other film ever has.

It was all in the details that appeared on-screen: the mannerisms, sayings, and staples of a Korean American household. When the patriarch, Jacob Yi (played by Steven Yeun), tells his young son in Korean to “Use your head,” my sister and I turned to stare at our dad, who tried to hold in his laughter. Jacob sounded exactly like him: “Think!” “Problem solve!”

But soon enough, we related to their experiences in a way that, at times, felt almost too close for comfort. Forty minutes in, my parents could no longer sit with the growing discomfort of witnessing all-too-real struggles of a non-white immigrant family trying to find a home in white America.

As Yoon hopped onto our Zoom call to talk about his time editing the movie, I told him that my parents and sister stopped watching it midway. (I finished it and had no regrets about it.)

Yoon knew exactly where my parents were coming from.

“The film is full of portrayals and relationships, and details that can be explosions of memory for someone who’s gone through that, particularly in a Korean household — I mean, I know it was for me, too,” he said.

Working with a predominantly Korean and Korean American cast and crew — including director Lee Isaac Chung, and actors Steven Yeun, Yuh-jung Yoon, and Yeri Han — to figure out how to present “Minari” was a deeply personal experience for Yoon. As the film’s video editor, parsing through all of the raw footage filmed for the movie as he wove them together transported him to his own childhood memories.

“There were times when I was watching the dailies [unedited footage] that I would start crying, because there would be a line or a look that felt so familiar to me, having grown up as an immigrant child. It just really brought back both the pain and the joy of that experience.”

Indeed, editing “Minari” was a project that allowed Yoon to tell an American, Korean American, immigrant, Korean American immigrant family story — a story that is just as much mine as it is for the fictional Yis and Yoon’s own.

***

Even as a student at the College, the signs were there that Yoon was meant to tell stories and work on films like “Minari.”

“When I came to Williams, I felt how powerful it was to take these classes and to hear stories that grounded me in the larger American story,” he said. “I’m just thinking, ‘Man, it’s so incredible to be able to talk about our stories in a way that felt legitimizing.’”

His first-ever video work took place at Williams. Yoon asked professors for permission to submit film projects instead of final papers; once, with fellow classmate Mark Rigby ’93, he produced a video on the issue of sexual assault for the College’s Health Center.

“Being able to tell stories, very difficult, intimate stories, honoring the people who were vulnerable and sharing them with us — that was the first experience [where] I had the power of good filmmaking and good storytelling,” Yoon said.

But while Yoon knew he loved to make videos, pursuing a career in film editing was a daunting decision for him that he made, gradually, over the course of the decade after graduation.

There was much at stake for Yoon, as he saw any career path he would embark on as a life journey closely tied to his family’s immigration story.

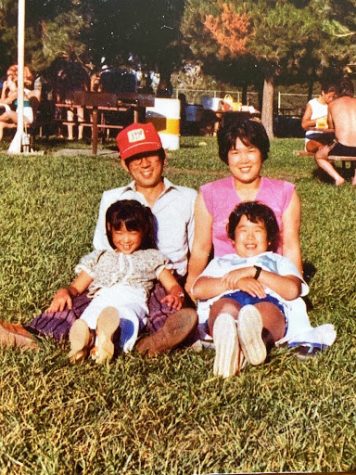

Yoon and his family immigrated to the U.S. from South Korea in the ’80s when he was 5 years old. Immediately upon arrival, Yoon’s parents worked tirelessly, opening small businesses and enterprises including a video store, a copy center, and a sandwich shop. “[They were] trying to do their best to sort of figure out how to fulfill the American dream,” Yoon said.

To Yoon, going into film felt like potentially gambling away all of his parents’ hard work — a feeling that I, as a senior contemplating a career in journalism with parents who also sacrificed so much, could relate to. I, too, know that a career in media is not something that is encouraged or modeled in many Asian American communities’ understandings of success.

“It’s definitely sort of a black sheep decision,” Yoon said. “It felt like a risk for our family… It’s a really tough decision to make when you see your parents sacrificing so much for your education. It feels a little selfish, and maybe vain.”

Convinced that this was true, Yoon delayed the decision to become a film editor for several years. Determined to refine his language skills, he headed to Korea upon graduating from the College, where he was peripherally involved in the Korean film industry through friends. Then, at the height of the dot-com boom, he returned to the U.S. to work at a start-up in the San Francisco Bay Area until it eventually faltered.

That was a breakthrough moment for Yoon: It was then that he would choose to go into film.

“I talked with my parents about it, I went to a therapist about it, and ultimately made the decision that I would regret it if I didn’t commit to filmmaking 100 percent for a while,” he said.

He enrolled in NYU’s graduate directing program in his late 20s but had to leave after one year for financial reasons. Soon enough, he was 31, an unpaid film intern making coffee and Costco runs.

That period of life was undoubtedly difficult, Yoon said, sometimes even demoralizing as he saw his peers getting promotions, building families, and achieving big milestones. Meanwhile, he was “starting over again, sort of at the bottom.”

“But I think ultimately what helped is finding a way to define your identity based on something outside of external circumstances,” Yoon said. “That’s been, you know, through a rediscovery of a Christian faith practice in which your identity is defined by God and not by yourself and not by the world.”

With persistence, he eventually rose up through the ranks of various productions, working on a wide range of shows and films including “Euphoria,” “The Newsroom,” and “Detroit.”

Through a colleague he had met while editing “The Last Black Man in San Francisco,” Yoon soon heard about “Minari.” He was immediately struck by how Chung’s script about a family grappling with finding home in America felt intimately real to him.

With the cast and crew, Yoon worked to present a story not typically seen in the American film world. It is one that a Korean American — or any immigrant, for that matter — could relate to for its honest look at family relationships.

That’s why Yoon was most nervous about showing “Minari” to his family members, despite the film already making waves at Sundance and with film award committees like the Critics’ Choice Awards.

Over FaceTime, Yoon helped his parents set up their TV to watch it, and he went to the Los Angeles Dec. 11 premiere at a drive-in movie theater with friends and his sister, Helen.

“It was really wonderful that [my sister] loved the film, could relate to it, and saw our family’s story in it,” he said.

Yoon’s parents, too, saw themselves in the film.

“And I think they were equally moved and felt seen. And for us, those were the most precious audiences and that’s what I hope: is that people will be able to see this movie with their families, and for them to feel seen, and to be able to have those kinds of conversations the way that we did.”

***

Right before we finished our call, Yoon paused.

“Jeongyoon, will you promise me one thing?” He asked me to make sure that my family would watch the film all the way through, and that I would tell him what they thought of it.

I nodded. “Of course.”

My family and I decided: we’re going to watch “Minari” — in full — this Friday.