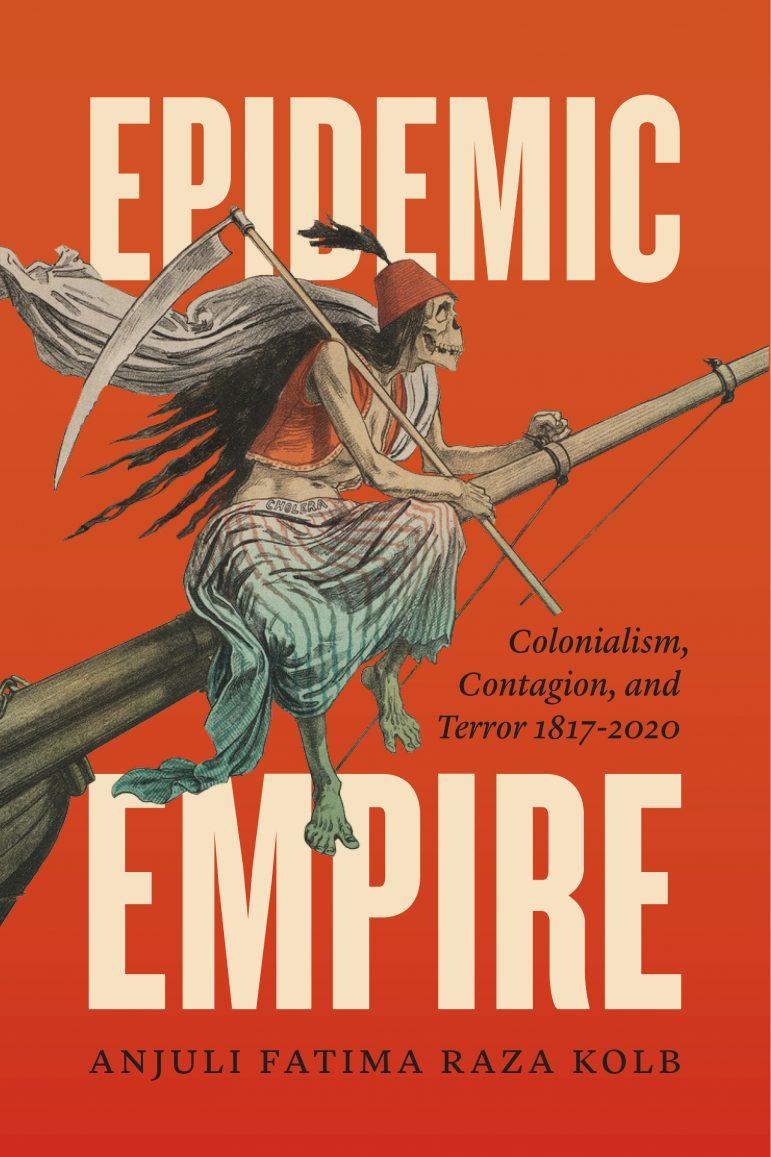

Even before the pandemic, Associate Professor of English Anjuli Raza Kolb was finishing up her book Epidemic Empire: Colonialism, Contagion, and Terror, 1817-2020, in which she investigates the relationships between terrorism and disease.

At the beginning of 2020, Raza Kolb was finishing the final edits of her book and preparing for it to go to print. However, once the United States was forced into a quarantine at the beginning of 2020, her plans changed a little. “Suddenly, this book is about the thing that’s happening all around us,” she said. Inspired by the current events, she wrote a new preface for her book.

The COVID-19 pandemic changed more than just the preface for Raza Kolb’s book. This time last year, not many people would have been interested in her research. “It’s a funny thing to be working on something that everybody is like, ‘Oh, that’s interesting. You have your weird little nerdy concerns,’” she said about her experience writing pre-pandemic. “And then suddenly, everyone cares about nothing but race and pandemics.”

The seeds of her book were planted when Raza Kolb was studying for her bachelor’s degree at Columbia University — and the World Trade Center was struck by two planes. “I was a junior on that morning, was in class, taking a course with Professor Robert O’Meally about jazz in American politics,” she said. “And by the time we came out of class, the towers were down just a couple of miles from us.”

The Sept. 11 attacks caused an outpouring of hatred towards Muslims in the United States. “It was almost as if all of these previous moments in history that had pitted Muslim culture against Christian culture were roaring back into focus,” Raza Kolb said.

“And in that moment, American Islamophobia basically had a renaissance,” she added.

Raza Kolb, curious about the cultural turmoil unfolding around her, began to ask herself some big questions: “What are the myths that are coming out of George Bush’s mouth?” and “What are the cultural backgrounds that make it possible for somebody like Donald Rumsfeld to say, Islam or terrorism is a cancer on the human condition?” The latter question would serve as a starting point for her new book.

After 9/11, media outlets began to refer to Islam as a contagion, a virus, a plague, Raza Kolb said. As a Pakistani American, she observed this and became intrigued about the association between Muslims and disease. “I was like, ‘What the hell is this history?’ And then I basically spent 10 years figuring out what that history was, and that’s what this book is.”

After she finished her undergraduate degree, Raza Kolb took a job at a publishing company. Here, she was introduced to the book-writing process for the first time. After she realized she was, in her words, a “bad editor,” she decided to go back to school.

“I went back to graduate school, basically, because that job taught me that I wasn’t done learning yet,” she said. She went to Columbia University to get her doctorate in English and Comparative Literature.

In her research, Raza Kolb uses discourse analysis to better understand historical texts and the times in which they were written. She explained this method as, “[taking] the close reading practices of literary analysis and [applying] them to something like a presidential speech, or a declaration of war, or signs of protest.” She said she views discourse analysis as an important way to examine historical events because “every ordinary speech act is influenced by literature and vice versa.”

Currently on leave from Williams at the University of Toronto, Raza Kolb teaches a mix of courses which examines British and colonial literature of the 19th century, as well as post-colonial literature. Students she had taught at Williams helped her with the research for her book. “I had five amazing research assistants, all of whom were students who had taken multiple classes with me, so I knew them well,” she said of five alums, Stef Hernandez ’19, Paul Griffith ’19, Leonard Bopp ’19, Rachel Clemens ’17, and Erin Hanson ’19. “They were incredible.”

Raza Kolb’s motivations for her research lie in her interest in “pursuing questions that have to do with what I would call forms of imperial knowledge that we take for granted and imagine are sort of normal and scientific,” she said.

One of these questions, she said, is “How do we denaturalize these big categories that we take to be sort of politically neutral, like human rights or or medicine or epidemiology, and open them up to see the history of power that’s embedded in them and in their discourses?”

Put simply: “What is this thing that looks pretty, nice, and normal? And then how do you start opening up that history?”

She added that one of the goals of her research, as opposed to just correcting history, is to help “us to confront our present in more ethical, and less racist and less ableist ways,” she said.

Raza Kolb said she is excited for the book’s release next week and the conversations that will follow it. “I really do look forward to having conversations with people who are passionate about this, not just as scholars, but as human beings, as ethical people in the world,” she said.