Digging into the data from the 2019–2020 Honor Committee report

December 9, 2020

The Honor and Discipline Committee, which adjudicates suspected violations of the College’s academic honor code, has released its report for the 2019–20 academic year. The report — and interviews with members of the committee who compiled it — provides insights into what kinds of cases the committee heard last year and how the cancellation of in-person classes this spring affected honor-code violations.

Number of cases: Significantly lower in the spring

Most striking is the dearth of cases the committee heard in the spring. Over the fall 2019 semester and Winter Study 2020, the committee heard 12 cases involving a total of 16 students, according to Dean of the College Marlene Sandstrom, who serves on the committee in a non-voting capacity and compiles the reports. But in the spring, the committee heard only three cases, with a total of three students.

The significant drop in honor cases came as the COVID-19 pandemic led the College to cease in-person classes and make every class mandatory Pass/Fail.

“With Pass/Fail, students might have felt like there was less academic pressure immediately on them — I know that maybe some students felt like there was more,” said Morgan Noonan ’22, who is this year’s student chair of the Honor and Discipline Committee and served on the committee last year. “But I could imagine circumstances where if students felt like it was Pass/Fail, maybe they were less obligated to pull all-nighters and put a lot of pressure on themselves.” The reduction in academic pressure could have led to a drop in honor-code violations, Noonan said.

Noonan said another possible reason could be professors’ reluctance to report suspicious activity to the committee in recognition of the pandemic-related stress that students were under.

Professor of History Gretchen Long, who was the faculty chair of the committee last year, also suggested that the low number of cases could be related to ways faculty adjusted their assessments to remote learning.

“Professors really had to change a lot of their assessments on the fly,” she said. “They may have done more essays or collaborative projects. Since they couldn’t be in the room anyway, they may have had more open-book-type exams.”

Of the 19 total students who came before the committee last year, 13 (68 percent) were found responsible for violating the honor code, with the remaining 6 found not responsible. Although this rate of students found responsible for honor-code violations is significantly lower than the mean rate over the prior decade (87 percent), it is in keeping with rates from 2018–19 (73 percent), 2017–18 (68 percent) and 2016–17 (75 percent).

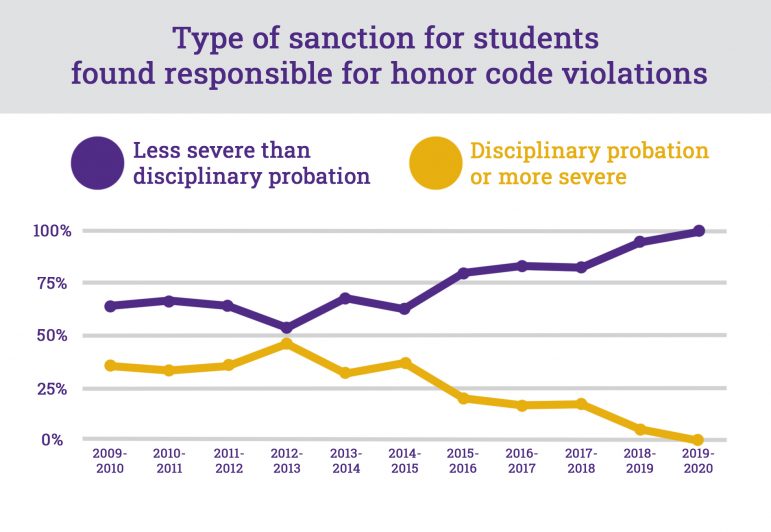

Severity of sanctions: On the decline

Also noteworthy is that no sanction was stricter than failure in a course. That no student was suspended or expelled for violating the Honor Code is hardly surprising, given that suspensions and expulsions have long been rare. Of the 213 students found responsible for violating the honor code in the last decade, only one student was expelled and eight students were suspended. What is more surprising is that no student even received disciplinary probation (which usually accompanies failure in the course).

Instead, students who were found responsible for honor-code violations failed assignments or courses. One student who came before the committee in the fall did receive disciplinary probation on top of failure in the course but then, after an appeal, had their sanction lessened to just failure in the course.

Before the 2018–19 academic year, students had to report any Honor and Discipline Committee sanction to graduate schools or employers when asked, even if the sanction was as minor as failure in an assignment. In the fall of 2018, however, the committee changed its rules. Now, the only reportable sanctions are disciplinary probation, suspension and expulsion.

The severity of sanctions has been declining for several years. The percentage of honor-code violations sanctioned with disciplinary probation, suspension or expulsion has dropped from 46 percent in 2012–13 to 0 percent last year.

“Disciplinary probation, suspension and expulsion are really used for cases that are deemed egregious violations, or if they’re subsequent violations of the honor code,” Noonan said. “So I think it could be a mixture of that we didn’t get any cases where we’d deem any of those sanctions necessary [and] that the Honor Committee has been shifting to be a little bit more lenient with students and keep this idea of redemption in mind, which sometimes disciplinary probation doesn’t really allow.”

Class-year breakdown: More seniors than is typical

Although 19 students is a small sample, the class-year breakdown is still notably different from that of the prior decade. First-years accounted for the most honor cases in the aggregate over the prior 10 years, and the most honor cases in five out of 10 years. Never over the past decade have seniors been the most prevalent class year among students brought before the committee, or first-years the least prevalent class year (though they did tie with juniors for least prevalent in 2015–16). But last year, nine of the 19 students brought before the honor committee were seniors, five were juniors, three were sophomores and only two were first-years.

Top subject involved: Computer science, as usual

Last year, in keeping with previous years, computer science was the No. 1 department represented in honor cases. According to Long, this is in part because it is easy for computer science professors to catch cheating.

“I think the professors have a certain expertise at spotting unusual code — or code that to a layman’s eye doesn’t look similar, … but actually the inner workings of it are too similar to be coincidental,” Long said.

Another reason, Noonan said, is that students are not always clear about what kind of collaboration on their code is appropriate. Yet another reason could be the large number of students enrolled in computer science courses.

“A lot of students take comp sci,” Long said. “I mean, those classes are quite large. They are the leader in honor code allegations and violations, but also, it’s a lot of students.”

Descriptions of cases: Intriguing as always

As usual, the committee’s annual report contains short descriptions of the year’s brazen, heartbreaking or occasionally bizarre alleged violations of the honor code. While these descriptions can provide useful quantitative data in the aggregate, they can also serve as qualitative looks into how students commit (or don’t commit) academic dishonesty and how the committee decides its cases.

Last spring, one sophomore was brought before the committee for three separate alleged violations in one class: claiming to have turned in a hard-copy assignment when they hadn’t, claiming (somehow) to have turned in an electronic midterm when they hadn’t and turning in an assignment late after accessing the answer key that had been uploaded to Glow. The student admitted to the latter two violations, while maintaining they really had turned in the hard-copy assignment. The committee accepted this version of events and sanctioned the student with failure in the course.

Perhaps the strangest case of the year was the junior who had to face the committee after submitting “a block of computer gibberish rather than content” for two assignments. “The professor was concerned that these submissions could potentially represent the first step in an attempt to deceive (i.e., if the student then subsequently requested additional time to submit an ‘uncorrupted file’),” the report noted.

But the student had an explanation. They told the committee that they had given up on passing the course — so they had no reason to cheat.

“They stated that instead of completing the assignment, they wrote a note to the professor indicating that they could not complete the assignment, and then sent that note on a ‘broken’ computer that they were aware might corrupt the file,” the report reads. “While the committee had a hard time understanding the student’s thought process, they agreed that submitting a gibberish document in and of itself did not constitute a violation of the honor code.”