Ephs share stories from staffing campaigns in battleground states

December 9, 2020

In the middle of their careers at the College, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of students made a choice this fall to drastically uproot their lives in order to work as campaign staffers for the 2020 general election.

Several students took advantage of College policies that allowed returning sophomores, juniors and seniors to opt for a personal leave and followed what they described as an urgent calling to get involved in electoral politics full-time. Others, who ended up enrolling for the fall, had already worked on campaigns over the summer or managed to hold part-time remote jobs on top of their courses during the semester.

Whether they took time off or enrolled, students especially gravitated towards campaigns in key Senate battleground states, including Maine, North Carolina, Colorado, Iowa and Montana.

Rwick Sarkar ’23.5 worked remotely as a field organizer in Iowa, where Democratic candidate Theresa Greenfield challenged incumbent Republican Sen. Joni Ernst. A Massachusetts resident, Sarkar had previously volunteered for Sen. Elizabeth Warren’s campaign during the Democratic presidential primary and eventually served as the point person for his home state senator in the Berkshire region. He led several canvasses in Pittsfield and Williamstown in the run-up to the Massachusetts primary on Super Tuesday.

“I’ve had an itch to be involved in this election for a while, but I don’t think I ever really planned on taking the fall semester off and fully jumping in,” Sarkar said. “I expected to volunteer a little bit, but it was a combination of people just realizing what the stakes in the election were, and COVID hitting, and Williams making it that much easier to take the semester off. I had those 10 days in July to make that decision.”

He was onboarded a month later in mid-August and assigned to a pair of rural counties, one of which contained Grinnell College and both of which had gone for Barack Obama in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016. Though Grinnell was remote for the fall semester, Sarkar said many students had registered for the Iowa caucuses in February and were able to vote absentee.

Up until the election, Sarkar’s day-to-day work consisted of recruiting volunteers and holding phone banks over Zoom, which often included a mix of local Iowans and his friends from across the country. He said he felt encouraged by the sense of community that developed in many of the rooms.

Still, the election was tough for Iowa Democrats. Trump carried the state by 8 points and Ernst by nearly 7. Only one Democrat, a county supervisor, won in his two counties.

While Sarkar maintained that the Senate race was winnable, he added that as an organizer he understood the challenge when he took the job. “You don’t get into because you think you’re going to win,” he said. “If there’s no chance of losing, you wouldn’t do it.”

He remained hopeful for the future because of the volunteers that he trained and connected to local county parties and activist circles, from the retirees who were volunteering for their first campaigns to an 18-year-old local who might work as a field organizer herself one day. “I’m not going to make as much change as those individuals are in their own community,” Sarkar said. “… That, at the end of the day, is more powerful than a college student from Massachusetts coming out and dialing hundreds of numbers a day.”

Kitt Urdang ’23.5 was sitting at her home in Connecticut in September when she began to question her decision to unenroll for the fall semester. She was anxious to work, but no one was hiring — except she knew that political campaigns needed staffers.

She Googled, “What states have close Senate races this year,” and connected on EphLink with David Turner ’08, who worked as a field organizer for the Obama campaign in 2008. After hearing about Turner’s experience, Urdang decided to apply online for a similar position in Montana.

“I got a call for an interview, did some interviews, got the job and flew out three days after,” Urdang said. She joined the Senate campaign of Gov. Steve Bullock, a Democrat, in Republican-leaning Flathead County. (Urdang, who was an opinions editor at the Record before she took the fall semester off, was not involved in the writing or editing of this article.)

From her experience in Flathead County, Urdang quickly learned two things: that field organizing requires vigilant efforts at voter protection and that the state of Montana has a long history of distrust towards corporate interests in politics, dating back to the copper kings and the Anaconda Company that exerted influence of the early 1900s. “One of the biggest challenges I ran into was there was a lot of outside money going into the Senate campaign, and voters were really not happy about it,” she said.

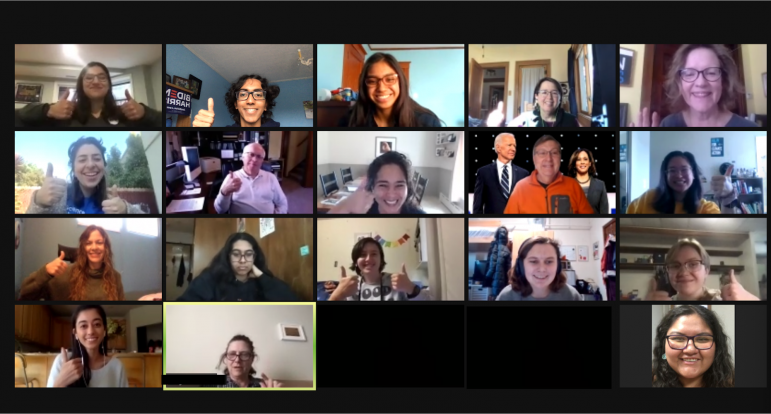

Like Sarkar, Urdang relied on her interactions with volunteers, especially her weekly Williams for Bullock phone bank, to keep her going. “Every single week, whatever was going on, I would be super excited for the Williams phone bank,” she said. Urdang’s volunteers would often text her after the phone banks to tell their stories about persuading voters, anecdotes that lifted her spirits when she would sometimes spend an entire day knocking on doors without having a conversation.

When election day finally came and Bullock and all but one of her candidates in Montana and Flathead County lost, the feeling was “heartbreaking” and “devastating,” Urdang said. After taking two days to gather her thoughts, she reflected on moving across the country in a thank-you email on the Thursday after the election to her volunteers, “The election, from the start, was going to be unlike any other. No one knows how to organize in a pandemic … I’m so proud of the way you all adapted to new challenges.”

The challenges in the westernmost county of Maine were also significant for Lilly Wells ’22.5, a field organizer who was drawn to the Senate campaign of Democratic candidate Sara Gideon. Wells, who grew up in western Massachusetts and knew she wanted to work in small rural communities, said that no local Democrats won in her county, though Democratic Rep. Jared Golden retained his congressional seat and a couple towns flipped from Trump to President-elect Joe Biden.

“There was one town, Brownfield, that Biden won by two votes,” Wells said. “Little instances like that make you realize how important every single conversation is. Those two people could have been people we reached.”

Wells moved to Maine in September and started recruiting and training volunteers remotely. She thought about ways to make volunteering more accessible, including providing a support system for those who were less comfortable making phone calls. When she and her team were able to safely resume door-to-door canvassing in October, she said she found a local population that was disaffected from politics after years of neglect. Many were non-voters. Others felt socially isolated amid the COVID-19 pandemic and wanted to chat, sometimes for half an hour or more.

“I definitely got the sense that, especially here in small rural communities that hadn’t had as much political investment in recent years, maybe 2008 was the last time that campaigning really extended to all these areas,” Wells said.

Despite the many day-to-day obstacles for Democrats in rural Maine, Wells said she was motivated by the enthusiasm and devotion of her peers nationwide. “It inspires me to hear and to know about all these other Williams students that were putting their heart into it as well,” she said.

In particular, she kept in touch with Chris Avila ’21.5, who worked in Asheville, N.C. on the Democratic coordinated campaign for the Senate and the presidency, as well as downballot state-level races.

Avila told the Record in September that he began looking into the opportunity as early as April and knew he would not enroll in the fall semester even before the email from Mandel announcing the College’s plans. “What can I as a 21-year-old be doing?” he said at the time. “I can drop out of school and make nearly a thousand calls a week and train and support a hundred volunteers to be doing the same. That’s what I can do, so that’s what I’m doing.”

The issues that motivated Avila to seek out a position on the campaign included climate change and environmental justice, he said. He has spent much of his time at the College researching the two and thinking about what needs to get done. Avila won the prestigious Truman Scholarship earlier in the year and plans to pursue a joint J.D. and M.S. in environmental science.

In September, he reflected amid the heat of the campaign that everyone brings their own issues to the work, but manages to come together seamlessly in pursuit of a common goal. “Elections have this really funny phenomena where there are a thousand reasons that you can get in the fight, that will motivate you to drop everything else and work really hard, but in a really interesting way they all get collapsed into just making calls and winning,” he said.

While those working for Democratic Senate candidates in red states fell short of their goal, Niko Malhotra ’24, who enrolled on campus in the fall, contributed over the summer in laying the groundwork for a surprising victory. After moving to Maine with his family in March, Malhotra staffed the reelection campaign of Republican Sen. Susan Collins, although he stopped working right before the semester started. “Throughout the fall, even though I worked on her campaign, I was like, ‘This is never going to happen. She’s never going to pull it off,’” Malhotra said.

He originally contacted the campaign by email and heard back about a position within a week: He would serve as the field organizer for the surrounding counties of Portland, mostly trying to reach a weekly goal of talking to 2,000 voters on the phone and putting together additional coalitions such as Veterans for Collins.

Like elsewhere, voter engagement was low at times with a campaign reliant on phone-banking rather than door-knocking, but Malhotra added that all the money spent by the Gideon campaign seemed to have little sway over voter opinion. “We were outspent by so much and that maybe played into people’s images that she wasn’t going to win,” Malhotra said. “That was surprising, that despite Sara Gideon’s having millions and millions more dollars — all the advertisements were Sara Gideon — it didn’t really have that much of a role in shaping how voters determined the race.”

One of the few students who staffed a victorious Democratic Senate campaign in the fall, Ben Platt ’23 remotely interned part-time for Gov. John Hickenlooper in Colorado while enrolled on campus. He worked 12 hours a week on top of courses and extracurricular activities, including leadership positions on EphVotes and the Mountain Day planning committee. After he applied mid-August and got the job, he onboarded while quarantining at the College.

Platt worked in the political department, where he managed relationships with top surrogates for the campaign, scheduled regular calls with leadership councils and collaborated on the planning of events. While the experience was not typical because of the pandemic, he said his team, which included other remote members, leaned on each other and created a feeling of camaraderie despite the circumstances. Though he would not want to take classes again at the same time, Platt said he wants to try a more traditional campaign office job in the future.

“This was a really enlightening introduction to that world,” he said. “It really is an ecosystem, everyone I talk to there, [and] there’s kind of like a dopamine rush. A campaign is non stop, you’re always moving on to the next thing.”

Platt said it was deeply gratifying to win the race. “We won by the largest margin in a Colorado Senate race in 42 years,” he said.