“If we are in charge of our own history, what happens is you get the truth,” said Director of Cultural Affairs for the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Heather Bruegl. “You get our story told from our perspective, and the story of the Stockbridge-Munsee people is one that I am even in awe of and I carry that blood through my veins.”

The history of the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians is indeed nuanced, but more than 175 attendees listened as Bruegl, Assistant Professor of History Christine DeLucia, Williamstown community leader Lauren Stevens, and Williamstown Diversity, Inclusion and Racial Equity (DIRE) Committee member Andrew Art discussed the tribe’s new historic preservation office on Spring Street last Thursday in a 90-minute panel over Zoom and WilliNet.

The webinar, sponsored by Boston University School of Theology’s Faith and Ecological Justice Program and moderated by Boston University School of Theology student and Williamstown native Rachel Payne, also touched upon the cultural background of the Stockbridge-Munsee and how best to incorporate Indigeneous voices into local history as the community relocates its office back to its homeland in western Mass.

The Stockbridge-Munsee community originated in the Mahicannituck River Valley, also known as the Hudson River Valley, which incorporates present-day Williamstown and Berkshire County. “When the colonists came over [in the 17th and 18th centuries], we were of course moved several times,” Bruegl said. “One of the areas we were moved to was Stockbridge, Mass.” Protestant missionaries, particularly pastor John Sergeant, arrived in the region not only to create the village of Stockbridge but also to convert the Stockbridge-Munsee to Christianity.

“The tribes in the Northeast and New England area were evangelized and Christianized extremely early on, but they always had a sense of who they were and what our history was,” Bruegl said.

After allying with the colonists in the Revolutionary War, the colonists pushed the community out of the Stockbridge area and westwards towards central New York in the late 18th century. Subsequently, colonists forced the Stockbridge-Munsee to relocate once again: this time to the west, eventually to their current reservation in Shawano County, Wis., in 1856.

“[The community’s background] is a really complicated history that I think is just starting to be told more fully,” DeLucia said. “Even coming up with the right language to describe that relocation is challenging, but one of the outcomes of that is that today, the tribe’s formal reservation area is in Wisconsin, and they are really, really keen to maintain connections to their Eastern homelands here.”

Although the connection between the Stockbridge-Munsee and the town of Stockbridge is evident today, the community’s relationship to Williamstown is just beginning to be understood in a fuller manner. Sharing a variety of maps and photographs, DeLucia explored the difficulties of welcoming a community back to a land from which it has been expelled. When perusing the Williams College Library Archives, she found one of the earliest maps of Williamstown – a colonial land claim about divisions of private property allocated to colonizers, with no mention of any Indigenous groups.

“Every inch of this continent is Indigenous land – both historically has been Indigenous land and continues to be Indigenous land – right through the 21st century and today,” she said. “Marking place has a lot to do with telling history and whose version of the past is most prominent.”

Bruegl, an enrolled citizen of the Oneida nation of Wisconsin and a first-line descendent of the Stockbridge-Munsee, emphasized the importance of providing an Indigenous perspective to colonized histories. “What I think is most important is that we’re able to give an Indigenous voice back to this land – we’re going to be able to talk about our history that happened in this area,” she said.

In order to do so, the Stockbridge-Munsee must be in charge of their own story so that historical accounts can include and be shared from their perspective without a colonial lens, she said. “In order to understand a lot of history that isn’t taught, there is a process of unlearning that needs to happen,” Bruegl said. “That can challenge a lot of people’s thinking and that’s OK – it’s OK to have your thinking challenged, and it’s OK to take in new information.”

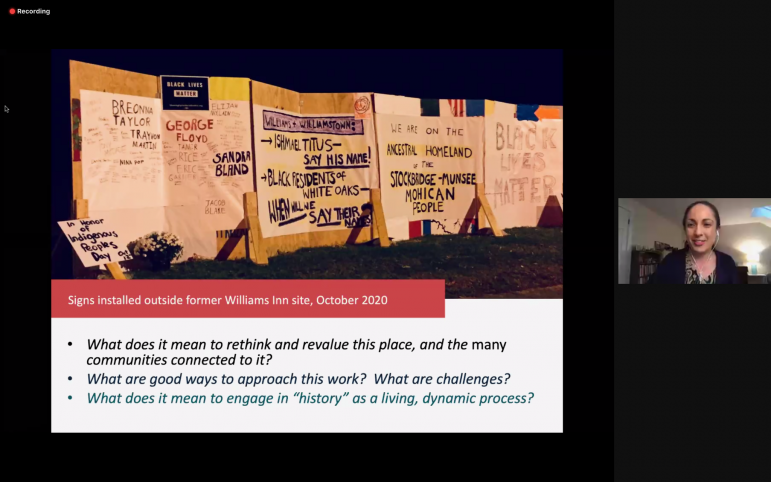

Williamstown is currently in this process of “unlearning” its history by implementing new signage that more prominently acknowledges the Stockbridge-Munsee community in the region, Stevens said. Located in the heart of Williamstown and a frequent space for protests and speeches, the 1753 House, a replica of some of the first houses built by European colonists, is one such site.

“At one of the talks, one of the speakers said while gesturing towards the House, ‘You know, there were people before this,’” Stevens said. “Someone who was at the rally took that to heart and wondered whether it would be possible to alter those signs to acknowledge that there were people here before those 1753 settlers.”

The Williamstown town committee, in conjunction with DIRE, endorsed this proposal and procured a sign that now includes the line “Homelands of the Moh He Con Neew (Mohican Nation).” Stevens admitted that although the creation of the sign is a good start, it by no means tells the full story of the Stockbridge-Munsee community in the area.

Art noted not only the town’s failure to embrace the tribe’s history but also his own shortcomings in learning about Indigenous people while growing up in the region.

“We moved to a neighborhood called Colonial Village, and I didn’t realize that that was established, originally, as a whites-only community,” Art said. “From there, we moved to a house on west Main Street in sight of the 1753 House, and my bus stop was actually right outside of the memorial … but I didn’t think about those people who were colonized and these monuments to the colonial past with total omission of any type of acknowledgement of Native culture.”

Art said that the new sign outside of the 1753 House is just a small step toward remedying a “whitewashed colonial celebration of perspective” that has erased the history of Stockbridge-Munsee people. “We have not come to this conversation with an acknowledgement of difficult and painful facts,” he said. “We have to account for that to begin a conversation to move forward, and we need to recognize our local history, and I believe that can be a community effort.”

The historic preservation office is a step towards this effort for the Williamstown community to learn more about the Stockbridge-Munsee people. Bruegl said that although the tribe enjoyed its previous location in Troy, N.Y., with Russell Sage College, Williams and the Williamstown area offered a relationship that understood the importance of the work the community wanted to undertake.

The office will oversee the protection of sacred and culturally important sites, the repatriation of significant objects and the retrieval of artifacts and remains of ancestors from museums, Bruegl said. Both she and DeLucia said that the College was immediately receptive to the idea of establishing a connection with the Stockbridge-Munsee to help preserve their history.

“We want to create a presence out east,” Bruegl said. “We want to have people know that we’re not the ‘last of the Mohicans,’ that James Fenimore Cooper got it wrong. … We are still here, and we are a strong and vibrant community, and we are fighting every day for our people, not just Stockbridge-Munsee but for Indigenous people in general.”