The Sticky Rice Project (SRP) held a series of workshops last Saturday on the “model minority” myth and the presence of anti-blackness in Asian American communities. A branch of the Boston-based Asian American Resource Workshop (AARW), the SRP is dedicated to educating the community about the political forces affecting the Asian American community while inspiring activism and conversation across campuses. This is its second series of workshops; the first was held at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Though the AARW was founded in 1979, this particular group of SRP facilitators – Alice Frederick, Shirley Li, Chris Lo and Andrew Yang – joined the team within the last few months. All four had been contemplating their own identities as Asian Americans and ways in which they could address the issues that they saw in their lives. One of their goals for the workshop was to give students the chance to talk about these topics early in their lives, an opportunity they felt they had lacked while they were students.

“For me, these were conversations I wished I had,” Lo said.

“It’s definitely starting conversations early, earlier than I ever had these conversations,” Li agreed.

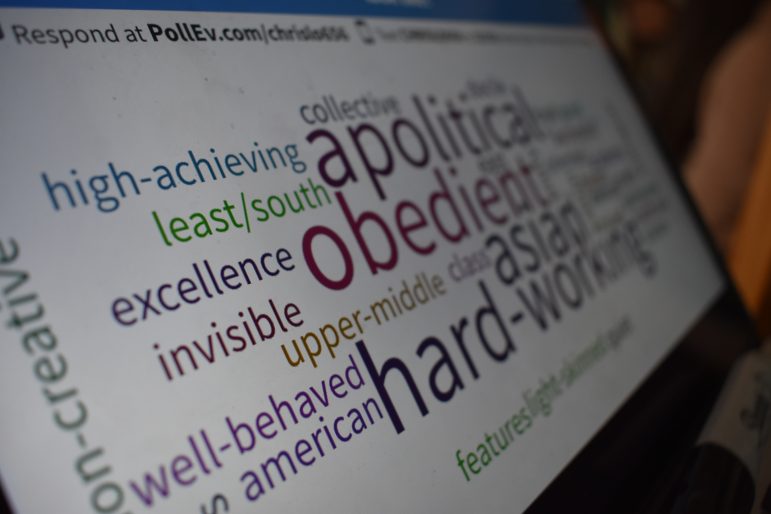

The event opened with the Model Minority Myth workshop, which aimed to define and destroy the “model minority” myth, illuminate the role that Asian Americans play in upholding white supremacy and highlight what has been done – and what can be done – to resist. The facilitators first had participants explore what defined their Asian American identities, from faith to social media to academics. Participants then collectively constructed a word cloud for how they thought the model minority and the stereotypical Asian American were perceived. Words that stood out were “obedient” and “apolitical,” among others.

The subsequent exploration of racism and power dynamics affecting Asian Americans was revealing, and many expressed surprise that the phrase “model minority” was originally coined as a critique for the civil rights movement. At the end of the workshop, participants made a word cloud for the same question again, but this time there were some striking differences: “obedient” became “complacent,” and “apolitical” became “silent.”

“I think this workshop has been an illuminating experience,” Audrey Koh ’21 said. “I really appreciate being able to come together with Asian American friends and new faces in a setting to discuss our Asian American personal and collective identities.”

After a brief lunch break, the group dove into a workshop on anti-blackness. In perhaps the most sobering moment of the day, participants formed a circle with everyone facing inwards and stepped into the center if they identified with the race-related statements they read. Each person was made to address their own relationship with anti-blackness as Lo went down the list.

The rest of the workshop focused on how Asian Americans interact with racism in the U.S. It explored the importance of unearthing the history behind anti-blackness in the fight against anti-black racism. The workshop ended with a conversation about the next steps that needed to be taken to combat anti-blackness.

Li expressed satisfaction with how the event turned out. “Everyone here is so passionate, and I can tell they’re invested in it in their own personal ways,” she said. “I think that’s incredible because everyone can start their own personal journey to figure out what this means to them. That’s pretty powerful in and of itself.”

Lo said he hoped that the conversations started at the workshops would spread throughout the campus. “This is a starting point of developing curiosity,” he said. “Having this space to talk about these things is a really powerful way to build that knowledge base and understand where each person is coming from, as well as a capacity to make lasting changes.”

This sentiment is shared not only by the other facilitators but by the participants of the event as well. “This is primarily a community-building exercise for the AAPI [Asian American and Pacific Islander] folks here to be better at supporting other POC [people of color] on campus, but also coming together around political education, rather than just an appreciation of cultures,” Annalee Tai ’21 said.