Collecting specimens from local frog ponds in the Berkshires, manipulating glassware and working with hazardous chemicals are just some of the activities originally designed for Division III lab courses that faculty have had to alter drastically or remove entirely since the College switched to remote learning.

This spring, Professor of Chemistry Jay Thoman ’82 is teaching a lecture and one lab section for CHEM 256: Advanced Chemical Concepts, while Lecturer in Chemistry Laura Strauch leads the other four lab sections.

Lectures are now recorded and put online, but Thoman said he has tried to “pantomime the think-pair-share experience” to retain the collaborative aspect of scientific work. In the middle of his lectures, he will often say, “Pause right now and try to do this on your own… or send a text message to your study buddies and try to figure this one out.”

Thoman also attempts to get students to meet synchronously in their lab sections via Zoom or Google Meet. “It’s not required, but encouraged,” Thoman said. “It’s really nice to talk with people when they can talk back in real time.” Each section originally contained between 8 and 16 students, though Thoman now allows students to collaborate between sections as needed based on time and technology constraints.

“We’ve gotten a pretty good turnout,” he said of the synchronous lab meetings. “I’ve seen 90 percent of the students in the class, roughly speaking.” Even if students cannot attend the meetings at that time, he records the 30 to 45 minute discussions and posts them online.

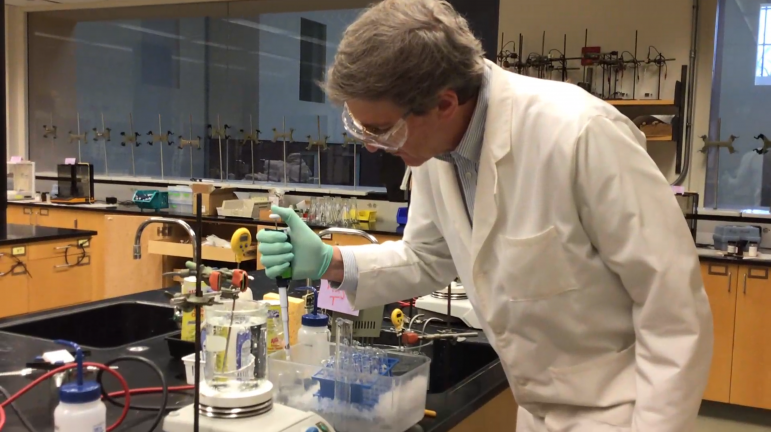

For Thoman’s students, remote learning labs mostly entail completing worksheets and lab reports, since conducting experiments in person is no longer possible. Usually, Thoman and Strauch perform the experiments themselves on campus and record it “Julia Child-style,” according to Thoman. “We show the set-up, and three hours later, you’re done, but we film it a minute later, like, ‘Oh, here are the results,’” he said. “We don’t record three hours of being in the lab, which is how long it would really take to do the experiment.”

They then upload the video of the experiment in progress and the data they collected for students to access. “We try and tell the story,” Thoman said, referring to the theoretical discussion that accompanies doing the experiment.

Since CHEM 256 usually constitutes the fourth semester of the chemistry major, students “have been in the lab for three-and-a-half semesters, and we can remind them of that,” Thoman said. “Like, ‘What we’re doing, back a year ago, you did a really similar thing in organic chemistry.’”

Regardless, the experience is not the same. “What they’re missing out on is hands-on experience… with doing what a large number of practicing chemists do,” Thoman said. “Watching experiments fail, breaking glassware, turning the temperature up too high or too low, not writing down a number that you really needed.”

“We’re all just doing our best to try and make a positive learning experience,” Thoman added.

Faculty in other departments are in similar situations, though the ways they approach adjustments to lab activities have varied. Derek Dean, lecturer in biology, is teaching labs for BIOL 102: The Organism, with 8 to 24 students in each section.

While on campus, BIOL 102 students did activities ranging from observing plant species’ evolution to studying developmental biology by handling sea urchins. “That’s very hands-on,” Dean said, but the activity originally scheduled for after spring break has had to undergo significant adjustments.

“We have this long experiment where we go out to these two local frog ponds,” Dean said. “We get some eggs, and the tadpoles hatch in the lab.” This population genetics study would allow students to extract DNA from the tadpoles and try to determine the health of the population. Now that most students are off-campus and unable to collect specimens in person, they are using data from last year instead. “I showed them a video of the frog pond so they could at least see what it looks like over a video,” Dean said.

Dean also hosts synchronous live sessions for students to work on practice problems together and ask him questions, similar to the sessions he would normally host on campus. He estimated that about half of his students have attended these sessions so far.

“I’m missing interacting with students directly,” Dean said, “That’s one of my favorite things about this, is to directly interact with the students. A challenge has been trying to make this an interesting, engaging experience and really have them get a sense of the lab.”

GEOS/ENVI 100: Introduction to Weather and Climate, taught by Professor of Geosciences Alice Bradley, has experienced a more unusual adjustment to remote learning. With just over 40 students and lab sections of ten students each, the course involves data analysis, climate-focused labs and weather observation assignments.

Prior to remote learning, the course already had some flexibility built in: outdoor labs were self-scheduled, and there were more possible assignments posted than students had to turn in, so they could choose which labs to perform. “I can explain a lot about the weather, but I cannot control it,” Bradley said. “I can’t count on it raining for the Monday afternoon lab group, the Tuesday afternoon lab group and the next week’s lab groups. So these outdoor labs have been do-at-your-own-pace whenever the weather is available for the lab assignment.”

“I adjusted a couple of [the assignments] to be a little easier to do in different kinds of climates,” Bradley explained. “So the hazardous weather one had been specifically a thunderstorm lab, but recognizing that some people are in places that are not gonna get these kinds of storms but that are going to get other kinds of weather, I could pretty easily adapt these to work wherever.”

Some assignments are also remote-friendly by nature, since they do not require students to be in a particular locale; one assignment involves fact-checking media reporting on climate. Students have thus been able to do these observations remotely, regardless of where they ended up. “We’ve really been able to take advantage of the breadth of weather that students have been experiencing,” Bradley added.

Still, some aspects of the course have become much more difficult to maintain. Originally, the last data analysis lab for the term was planned to be a climate solutions simulation in partnership with the Center for Environmental Studies (CES). “Because we’re not able to be in person and get everyone in the class online at the same time to do this big live simulation, we’ve had to cut that out,” Bradley said.

Bradley has also faced limitations on which software platforms students have access to off campus. Students formerly used Excel, Panoply and MATLAB for data analysis labs, but some of these platforms require substantial space and computational power on a computer, and it is more difficult to remotely provide “hands-on help for students that do not necessarily have the computer or data analysis skills already,” Bradley said. She ended up replacing the MATLAB-based lab that was interrupted by the campus closure with an assignment that can be done in Google Sheets.

“I think it’s important to acknowledge that the circumstances that we’re currently working under have been tough, but they’ve been varying degrees of tough for different people,” Bradley said. “Fortunately, weather is something kind of normal that we’re experiencing, and so I’ve tried in developing these assignments to make them both as approachable and reasonable as I can in order to both meet the content and skills goals of the class.”

Professor of Biology Joan Edwards’ class, BIOL/ENVI 220: Field Botany and Plant Natural History, has also experimented with having students explore the natural world in their own locations, scattered around the world.

When the course is taught on campus, “We have weekly labs, and we go outside, and we look at plants in their native habitat, learn to ID them, and really learn their personality,” Edwards said in an interview on Press Record. Now that learning is remote, “The hardest part is to work on how to teach observational skills, and to learn plants in the field and experience the natural habitats of these plants firsthand.”

Given the significant hands-on component of the course, Edwards said she felt dismayed at the initial news about campus closure. “I really wasn’t sure what to do.” She decided to restructure the activities so that they would be accessible despite distance.

Instead of observing and learning about the flora in Williamstown, Edwards’ students now study their own local flora. “That’s when I devised an herbarium collection process, where students would every week collect two plants from their native local habitats, learn about them, identify them, and then make a permanent record of them on a herbarium sheet,” Edwards said. This involves pressing the plant and adding a detailed label. The herbarium sheets will be collected at the end of the semester and enter the College’s record of this semester’s activities.

In spite of the strain of unique circumstances, Edwards and fellow College faculty have taken numerous creative approaches to the challenge of conducting laboratory classes online. “I tried to turn it around and make it more positive,” Edwards said.