Creatives in Quarantine: Izzy Levi ’23

April 22, 2020

I sit down to interview Izzy Levi ’23 — over FaceTime, of course — exactly five weeks after we both left Williams, upending our routinized lives on campus and replacing them with unstructured, quarantined lives elsewhere. We spend the first few minutes of the call sorting out technological difficulties, catching up as friends, and lamenting the seemingly inevitable flatness of online interaction. Still, after hearing Levi’s answer to my very first question, I cannot help but note that, even through a screen, she emanates life.

“Do you know — This is gonna be bad because I’m gonna get so sidetracked. Do you know that I had— Do you remember when Williams sent that thing that was like, ‘Decide what name you wanna send us’? I had such an identity crisis. I was like, ‘I don’t go by Isabel, but I’d feel weird if Isabel wouldn’t be my on-record name.’ Anyway, Izzy’s good. It’s I-Z-Z-Y.”

Levi moves through much of the interview like this, shifting between ideas as if she is swimming in them, never closing her statements so much as rolling herself into new ones. Her work as an artist reflects this malleability. Not only is Levi a photographer, painter and drawer; she also spends much of her time writing creatively.

Levi took her first photography class in eighth grade, after getting “really into those super ‘conceptual images,’ like this woman in a big black dress with a bunch of crows flying around her, on Pinterest and Flickr and Instagram.” Once she’d accumulated some experience shooting “all these insanely dramatic crazy photos of me in the middle of fields and stuff,” Levi entered high school, where she shot on film for the first time. “I was completely in love with it,” she said. “I just loved the process, and I’ve basically not shot digital since.”

There is something distinctly ‘Gen Z’ about Levi’s mode of existing. Her energy reminds me of the ways we’ve both grown up online, from her meme-derived figures of speech (“Writing just hits different”) to her frank discussions of social media usage (“I had a tweet draft that was ‘tbt to when I thought that I was actually addicted to my phone, cause this shit is something else’”).

Beyond these direct references to the Internet, though, Levi embodies another, less visible characteristic of the generation that grew up alongside the rapid development of technology.

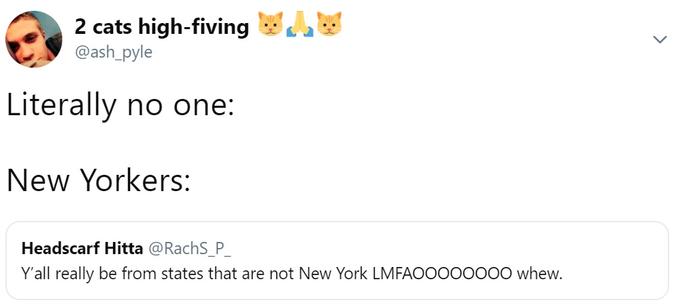

“I’m gonna get roasted for bringing up my gap year, like this is my version of

‘no one:

Izzy: ,’”

she says, alluding to a popular meme format. “But one of the main reasons that I decided to take a gap year was because I was so tightly wound and hard on myself and work-oriented throughout my time in high school. And basically I was like, ‘I don’t wanna burn out and drive myself insane.’ So it was kind of—”

She cuts herself off and looks at the paper she has been folding in her hands.

“How did I f*ck this up? I’m making a crane.”

Interruption aside, Levi articulates an experience familiar to many of us who went to high school in the 2010s, who learned how to be people at the same time that hyper-efficient, product-oriented innovation presented itself as the singular model of success. This kind of adolescence breeds a mentality that current Williams students know well, one that not only encourages moving through life quickly, but requires it.

Navigating this mindset has proved particularly complicated during the COVID-19 outbreak, as nations force themselves to slow down and stay home. For Levi, this phenomenon has drawn her closer to her artistic practice.

“I think so much about how this is realigning priorities that have been set basically my whole life, whether they were ever good or not,” Levi said. “In quarantine, writing has drawn me in in a way that I can’t justify saying ‘no’ to. It feels like a justifiable way to ‘waste time,’ which is such a capitalist way of how we look at work and productivity, but I’ll be like, ‘I’m producing something.’ And I feel proud of it.”

Indeed, while Levi spent much of her gap year honing her skills in film photography, painting, and drawing, she now finds writing to be her primary means of creative expression.

“There’s this weird sense of knowing that we’re living through this time that’s going to be so analyzed,” she said. “It feels like I have the opportunity to create this historical record, kind of, so I feel a compulsion to write more than I normally would. This is particularly true with poetry, because I didn’t write poetry really until this semester. There’s something about it that I’ve always struggled with. I’m like, ‘It’s just pretty-sounding images and words and, like, how do you think of that?’ But I’ve found that the mental state that quarantine has put me in has been weirdly conducive to accessing that kind of part of my brain.”

She pauses, then — in Gen Z’s darkly humorous way — adds, “This is a really fancy way of saying, ‘I’m so depressed that it’s making my writing better.’”

There’s something I find comforting in Levi’s candidness, in her unfiltered acknowledgment of the bleakness of life right now. I imagine it’s the same comfort that 616,000 people are finding on Facebook, in a group called “Zoom Memes for Self Quaranteens,” or that millions find as they watch the same TikTok depicting an all too familiar existential unease.

Both Levi and I — children of Instagram and iPhones — agree that social media is too “structured and calculated” to truly replicate the complications of knowing and understanding others. But if nothing else, it has reminded us that we’re all living this bizarre historical moment in tandem as much as we are in isolation, so we continue to log on, hoping for a connection.

Incidentally, this hope motivates Levi’s work as an artist, as her desire to make sense of this complex life collides with the impossibility of ever really doing so.

She creates anyway, of course.

“I’m used to writing in this super logical way, even about things that are super complicated and nuanced and confusing. And I think that that runs the risk of maybe oversimplifying certain things. There’s this illusion of, ‘This is exactly what I felt and this is exactly what I want you to get.’ But it’s not always so easy, or clear, or delineated. So I think in quarantine especially, with these feelings that I’ve never felt before, or that I don’t know what to do with, this new approach makes so much sense, to kind of just be like, ‘This is just what’s happening right now. And I don’t necessarily know what that means.’”