Large gatherings of students violated the public health guidelines. The College’s response has been spotty.

September 30, 2020

If you walk past Frosh Quad at 11 p.m. on a Friday, you’ll hear pounding music and see groups of first-years wandering between buildings.

It almost seems like a regular Friday night — not one in the middle of a pandemic.

In the weeks since students returned to campus there have been a number of instances in which students violated the College’s public health guidelines — which limit gatherings to groups of 10 — sometimes with gatherings of dozens of students. The College’s responses to different instances and types of violations have varied widely.

In what was perhaps the most blatant violation of the guidelines thus far, 120 students gathered near Poker Flats on Sept. 8, according to a Campus Safety and Security (CSS) report. A Junior Advisor (JA) who responded to reports of a large gathering near Poker Flats said that the majority of those present were first-years. The gathering dispersed soon after CSS officers arrived, according to Dean of the College Marlene Sandstrom.

No students were removed from campus and transitioned to remote learning as a result of this gathering, or any other gathering. As of Sept. 22, only two students have been removed from campus and transitioned to remote learning, according to Sandstrom. Both were removed for “arrival quarantine violations.” The removal of the first student, who said they attempted to swipe into two buildings without intending to enter them, resulted in the creation of a widely-circulated student petition advocating for them to stay. At the time, Sandstrom denied the appeal, although the student was later allowed to return to campus in September.

“Only a subset of violations result in transition to remote learning,” Sandstrom said in an email to the Record. These include breaking quarantine or isolation rules; violating travel restrictions or testing protocol; hosting or attending a gathering exceeding the limit of 10 individuals; hosting individuals outside of the Williams community; intentionally exposing to or threatening others with contagion; and repeatedly violating mask-wearing and social distancing guidelines despite warnings. However, apart from removing two students from campus for violating on-arrival quarantine rules, the College has not taken any enforcement action for violations of these guidelines.

Even as the large gatherings so far have not resulted in any removals from campus, the College maintains that it is “committed to applying our policy consistently in all cases,” Sandstrom said. “When we have concrete information about public health violations, we act on them accordingly.”

Both Sandstrom and Director of Campus Safety and Security Dave Boyer have stressed that all community members should assume responsibility for keeping campus safe. “For the reopening of campus to work, I felt strongly that CSS should not be relied on to be the primary enforcer of COVID-related rules and regulations,” Boyer said. “We are a very small department and we needed this to be a campus wide effort to have any chance of success.”

“We are counting on [students, faculty and staff] to speak up when they see unsafe behaviors or situations,” Sandstrom said.

When students submitted their intent to enroll this past summer, they signed their agreement to a “Community Health Commitment” affirming their compliance with a set of public health guidelines put forth by the College.

Still, in a Sept. 10 email initially directed at first-years, then forwarded to upperclassmen as well, Sandstrom outlined a list of modifications to the guidelines that strengthened CSS’s role in the enforcement process. She noted that “large groups of first year students have been congregating at Cole Field, by the river, Poker Flats, and Stone Hill.” In response to these gatherings, Sandstrom stated that CSS would begin requiring students who violate guidelines to show identification, which would then be shared with the Dean’s Office.

However, according to Boyer, CSS is still primarily “giving guidance” without asking for identification, and will only do so when students “choose not to cooperate or are recognized by officers as repeat offenders.”

Camryn Taylor ’24 said she felt Sandstrom’s Sept. 10 email was unfair, because Taylor believes it’s only a small minority of first-years attending very large gatherings.

“I think that there are definitely some freshmen who have broken the guidelines, but I feel like a large majority have been doing pretty well,” she said. “It felt very targeted at the freshmen when I think a lot of it had to do with other upperclassmen as well.”

The CSS reports contain a number of other instances where officers have responded to complaints of groups of students congregating in violation of guidelines around Frosh Quad, Cole Field and other locations.

JAs’ shifting role

As reports of first-years violating the College’s public health guidelines continue, JAs have expressed frustration about their ambiguous role in enforcing the guidelines. Increasingly, JAs have had to assume responsibility for reminding first-years to abide by the guidelines and for responding to large gatherings of first-years, which conflicts with their role as non-disciplinary, peer-to-peer mentors.

“We feel like the social distancing police, which is really disheartening and something we never imagined being as JAs. In many ways our relationships with the entry as a whole is fractured, but I think the JAs have responded very well to build community,” one JA told the Record on condition of anonymity. “We were told by the deans that we would never have to be policing health guidelines, but there we were on the quad telling frosh to be safe so that we all don’t get sent home.”

In some cases, first-years have pushed back against JAs’ requests to maintain social distance. “Many just acquiesce and then go back to gathering in large groups when we are not looking; others at least during the first days would react adversely,” the JA said. “In fact, one of my peers was called a ‘bitch.’ Again, they think we are narcs, but really they just do not understand that getting sent home for some kids would be unbearable.”

Theodore Anderson ’22, who is also a JA, called on the administration to pay JAs a stipend given their increased responsibilities this semester.

“We spend a ton of time on these issues and it adds a lot of stress. Moreover we are more isolated from our friends more than ever,” Anderson said. “Obviously as a JA you sign up to live with frosh, but this year we are confined to pods and even still it feels sacrilegious to interact with our friends because we might be putting our frosh at risk.”

JA Advisory Board (JAAB) Co-President Surabhi Iyer ’21 agreed that this years’ JAs were facing greater pressures than in past years. She said she recognizes the tension between reminding first-years of the rules and remaining a non-disciplinary mentor.

“I know that JAs have tried a lot of different ways to talk to their frosh and be there and be peer-to-peer mentors,” she said. “I really commend the JA class for everything they’ve done so far. … JAs didn’t sign up for this particular responsibility and so I think that it’s unfair to expect that they enforce social distancing rules without support from other campus offices.”

Fellow JAAB Co-President Peter Le ’21 added that JAs should “exemplify” good behavior, which he said includes gently reminding students to follow guidelines, but should not go as far as threatening to call CSS or initiating disciplinary proceedings.

In an attempt to keep JA responsibilities within reasonable bounds, the College created a new role over the summer: Residential Life Advisor (RLA). Primarily filled by coaches and Davis Center staff, the role gives JAs another option to contact for help aside from JAAB, especially when dealing with violations of public health guidelines.

For example, if a JA tells one of their first-years that they need to wear a mask when they are outside of their dorm room, and the first-year does not comply, the JA might first go to JAAB for advice. Le explained that JAAB can have a serious conversation with the student or give the JA advice on next steps.

RLAs are the “next level where they can also hold these conversations about lower-level social distancing violations or even bigger residential life issues” if conversations with JAAB prove ineffective, Le said. “[It was] mostly created for the purpose of holding conversations or interventions that are non-disciplinary in nature for these COVID-related infractions.”

The idea is that a meeting with RLAs would signal the seriousness of the situation, Le said, without needing to engage the disciplinary process or involve CSS. “[It creates] another level on which there are more responsible adults or employees that are trained to mediate these different conversations,” he said.

According to Le, however, this framework has not panned out in practice, and most enforcement has fallen on the shoulders of JAs. Iyer added that JAs went through some COVID-related training scenarios over the summer, “but it’s so hard to prepare for the actual reality because we didn’t know what it would be like — nobody knew.”

“I’m really hoping that administrative figures and RLAs in particular step [in] because this seems like this is the thing [RLAs] were created for.” Iyer said.

Taylor agrees that enforcement has largely fallen on JAs — but for good reason. According to Taylor, students feel uncomfortable reporting violations to CSS because they don’t want to be the reason someone gets sent home. In her view, there should be an initial, non-disciplinary discussion with a JA before a more formal authority figure gets involved.

As of publication, JAAB had met with Dean Sandstrom once to discuss reports of large gatherings of first years. During the meeting, Sandstrom clarified COVID guidelines for JAAB and recognized that their worries about gatherings were legitimate, according to Le.

Dean Sandstrom sent the Sept. 10 email addressing guideline violations soon after this meeting.

In Record survey, 65 percent of students say they have violated guidelines

In an anonymous Record survey sent to 500 randomly selected on-campus students, 217 students responded, with 74 percent indicating they believe the degree to which the College has enforced public health guidelines for students is “just right.” Only 9 percent of respondents said they felt the College was “too strict,” while 16 percent said “too lenient.”

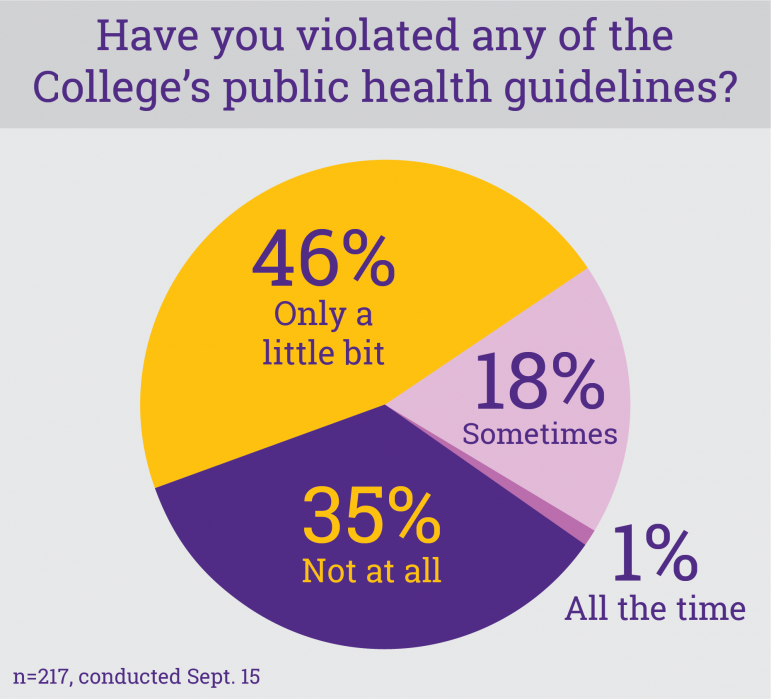

Of the respondents, only 35 percent claimed to have not violated the College’s health guidelines at all since coming to campus. 46 percent said they have violated the public health guidelines “only a little bit,” 18 percent “sometimes” and 1 percent (two students) responded “all the time.”

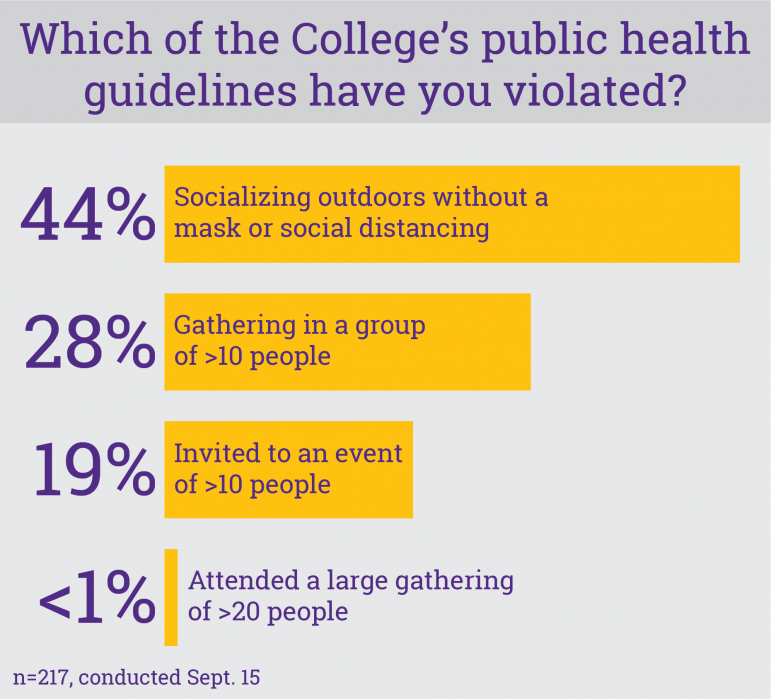

By far the most frequently committed violation respondents checked was socializing outdoors without a mask or social distancing (95 students), followed by gathering in a group of larger than 10 people (61 students). 19 percent indicated that other students had at least invited them to attend an event with more than 10 people. Only two respondents said they had attended a large gathering of over 20 people.

In comparison, in an earlier Record survey sent to students this past July, 27 percent of respondents said they planned to see one or more non-podmates without being six feet apart and 11 percent professed their intent to attend parties outside of their pod.

Taylor said that while she has not attended any large gatherings, she has heard about them happening on Frosh Quad and Cole Field.

“I’ve heard some [entrymates] discuss them,” she added. “[They] went to one and said that no one was wearing masks, so they left.”

A student who spoke with the Record on condition of anonymity due to concerns of disciplinary repercussions also said they have not participated in any large gatherings, but have inadvertently violated other guidelines. “I broke the prohibition on food deliveries before September 14,” they said. “I’d forgotten it existed, placed an order for no-contact grocery delivery, and been reminded of the prohibition too late to cancel the order.”

The student also broke the more recent rule announced by Sandstrom preventing students from exercising on off campus areas after dark. “I’d been planning a solo hike that wouldn’t get me back till after dark, and wasn’t willing to abandon the trip when the curfew was put in place,” they explained. “I felt that breaking the curfew alone posed no significant infection risk to anyone.”

While the student said they find the guidelines confusing and more emotionally taxing than expected, for the most part they feel the College’s enforcement has been reasonable.

“I’m somewhat concerned by the recent involvement of CSS in monitoring gatherings, since there’ve been complaints of biased enforcement and negative student-CSS interactions in the past,” they added. “But I also think it’s important that serious violations of limits on gathering be enforced.”

As it gets colder and workloads increase, Iyer said she thinks there will be fewer of these large gatherings, so the problem may resolve itself.

But thus far, as each weekend comes and goes, gatherings continue seemingly unabated.