Professors look back at remote learning, reflect on experiences and challenges

May 13, 2020

At the beginning of the switch to remote learning, the Record spoke with a variety of professors about their thoughts going into online classes. This week, we followed up with some of those professors as the semester comes to a close after a month and a half of remote learning.

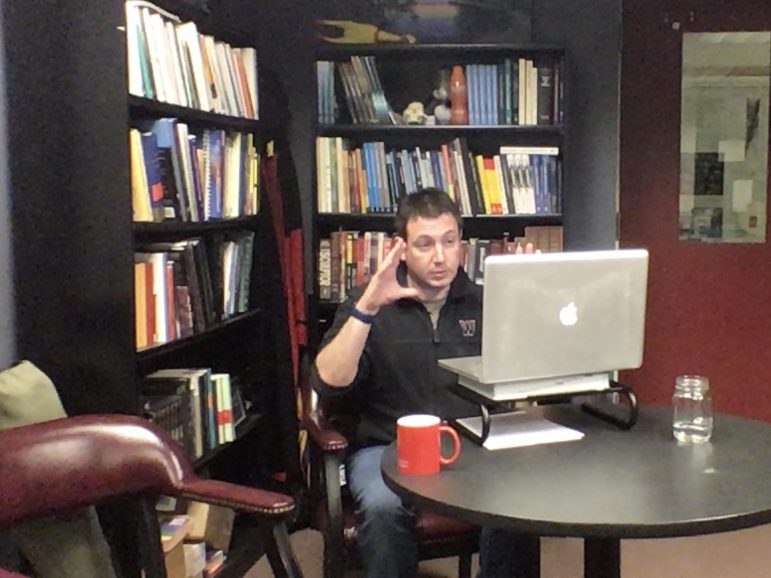

Associate Professor of Biology Matt Carter’s socially distant days are busy.

“Seniors are applying for jobs, or they thought they had jobs and now they’re having to reapply for things,” he said. “So, I’ve been doing so many phone references.”

He’ll spend an hour or two on that each day, then committee and departmental meetings, then letters of recommendation for medical school, and “then finally it’s like, ‘Oh I’ve got 30 minutes to work on the next PowerPoint before I have to see the kids again,’” he said.

Faced with children and other responsibilities at home, with limited ways of checking in, professors say it’s hard to gauge how their students are doing, and that virtual teaching techniques have restricted the ways they can engage and communicate with their students.

While Carter said he is still optimistic about remote learning because he can tell his colleagues are trying their best to make it work, the nervous excitement he felt at the beginning of the semester — the sense of possibility and new beginnings — quickly dissipated.

“It feels like a spare tire situation, like one of the tires just went out so you have to go to the trunk and put on the spare tire, and everyone is just sort of adjusting to the way that the drive feels now that we have the spare tire on,” he said. “I’ve definitely learned a lot from it, and, if I stick with that analogy, I’ve learned to drive better because of it.”

Carter and his wife split childcare responsibilities, he said, so he spends about four hours each day watching his kids.

“I go back and forth between thinking, ‘How am I going to do everything during the day?’ And then feeling lucky that I get to think about that,” he said.

But he said that he doesn’t want his students to pity him. He’s happy to help.

Associate Professor of Geosciences Phoebe Cohen said that having to balance her work schedule with childcare has actually helped her stay organized.

“Ironically, having my kid to take care of actually helps me,” she said. “Because I only have very specific hours in which to work, it forces me to be hyper-focused, which I’m really thankful for because if I had whole days with nothing structured or scheduled it would be much harder for me to get work done.”

Carter and Cohen both said that not seeing their students in person has made it more difficult to understand what’s going on with them. Online communication is just not enough, they say. Through mini-quizzes at the end of Cohen’s lectures, she knows that some students space out their work over the course of the week, and some do it all at once. Maybe that works better for some people, but it still worries her.

“Some students are in more communication with me than others, and that’s totally understandable,” she said. “It’s just so much easier when you see people face-to-face two or three or four times a week to get a sense of how they’re doing and if they need help.”

Cohen added, “I think I don’t guilt my students into doing work, but when you see someone and you interact with someone personally, I think there’s a different sense of accountability there that’s really hard to reproduce online.”

Professor of History Anne Reinhardt was also surprised at the disconnect she felt from her students while teaching online. “I had hoped to have more interaction with students, and I don’t feel like that’s really happening.”

With online Glow posts and optional discussions for her course on modern China, Reinhardt has found less than a third of her class joining the Zoom meetings. “I miss feeling like I have contact with the whole class on a regular basis,” she said. “I also feel like students aren’t really asking for help in the way that they would when they’re on campus … I hadn’t expected to feel the difference as much as I have.”

“It’s like all shots in the dark,” she added.

While Professor of Art Laylah Ali ’91, who is teaching introductory drawing and painting classes this semester, said that although her classes have gone better than expected, she has also struggled with the lack of individual, live contact with students. “I do a great deal of individualized instruction in class, walking around watching them work,” she said. “Particularly for students who struggle, that in-person time cannot be replicated as effectively online.”

Without face-to-face interactions, Carter said he feels like his reason for teaching has been taken away.

“A lot of teachers talk about the joy of seeing when someone has gotten something,” he said. “When you explain something, and there’s this ‘tada’ moment where you can see someone’s face visibly change because they either get something or they’re delighted by something or they appreciate something. Now those ‘tada’ moments happen remotely.”

His lecture class, despite having 72 students, felt like a conversation when it was in person. Now, that feeling is gone.

“It’s really awkward and frustrating to spend hours preparing something and then, instead of actually giving in front of people, I just hit a button and I’m done. It’s so weird. It’s like rehearsing for a play and then instead of performing the play in front of an audience, you just hit a button and then it’s done,” he said. “I’m genuinely surprised about how anti-climactic the experience is.”

For Ali, this experience has highlighted the complexity of live classrooms. “Online teaching has made me more aware of how layered and multifaceted in-person teaching is,” she said. “I truly miss seeing the students in our classrooms and on campus and the particular energy and excitement that can generate.”

Reinhardt felt similarly. “I think for all of us we’re missing some of the components that make it a lot more fun.”

Still, after teaching for years, she has appreciated the chance to get to know her course material in a new way by adapting her syllabus to an online format. “I’m actually kind of enjoying doing the preparation and setup for it; it’s getting me into this material in a different way,” she said. “Professors are kind of people who signed up to socially distance their whole lives, we tend to be sort of used to working on our own.”

Cohen also pointed out some silver linings. She has talked to colleagues about how some students have started participating more since remote learning began.

“Students who normally don’t feel comfortable talking a lot in class do feel comfortable engaging in online discussion on Glow about something,” she said. “They feel like they have more of a voice when they’re typing [rather] than speaking publicly.”

Cohen has been using an app called Perusal where students can collectively annotate journal articles, which she can respond to. She said it helps clarify parts of articles that the whole class finds difficult and would otherwise struggle through without understanding or simply skip.

Other aspects of her classes are just not the same online. Students reported that her virtual lab, while it gave the gist of the lesson, could not replace handling physical samples. Her classes also went on virtual field trips, which Cohen explained were sort of like “illustrated New York Times articles.” They’re good, and indispensable in times like these, but the experience of collecting data in the field is irreplaceable.

Ali’s students have also struggled with replicating the experience of a hands-on class remotely. “The students, of course, have experienced a variety of notable issues, including not having adequate work space or simply lack of peace and quiet,” she said. Still, her students have been adjusting. “Creativity is adaptable and flexible, and artists are often good with rising to these kinds of challenges,” Ali added.

Remote courses have also allowed for previously unthinkable moments in class. Once, while she was recording a lecture, one of Cohen’s children yelled that he had “a poop in his diaper.” His comment made it into the lecture.

Carter’s daughter ordered him to get her a brownie during a departmental meeting over Zoom.

“She wasn’t just asking politely for a brownie, too – she was saying, ‘Daddy!’ She was screaming about it,” he said. “But everybody’s been really understanding, though. If anything, it’s just made everybody laugh and been a little bit of comic relief.”