In an all-community email sent yesterday, President Maud S. Mandel announced that the College would maintain a two-semester model for the upcoming academic year while lowering the minimum required number of courses per semester from four to three and eliminating Winter Study. These changes will take effect whether or not the College resumes in-person classes in the fall; Mandel has set a deadline of July 1 to determine whether or not classes will be held on campus.

In an interview with the Record, Mandel cited the burden that students feel with remote learning as a reason to reduce the number of required courses. She also noted her belief that, if students are on campus, the changes could minimize the number of classrooms in use and therefore reduce COVID-19 spread. However, she clarified that students will still have the option to take more than three courses if they wish.

The administration decided to cancel Winter Study, according to Mandel, because they did not believe it would be a fulfilling experience remotely. In addition, a winter resurgence of COVID-19 could jeopardize an in-person Winter Study, whereas cancelling the term could potentially create a buffer to determine the logistics of the spring semester.

Mandel reached a decision alongside senior staff and faculty representatives, including members of the Faculty Steering Committee (FSC) and the faculty chairs of the Committee on Educational Affairs (CEA), the Curricular Planning Committee (CPC) and the Honor and Discipline Committee. Though the group collectively made the decision to maintain two semesters, lower requirements and cancel Winter Study, significant decisions have yet to be made. Next Wednesday, the full faculty will vote on whether to reduce the number of classes required for graduation from 32 to 30 for all students enrolled in the 2020-2021 academic year. In the coming weeks and months, individual departments will assess what these changes mean for major requirements.

Distributional requirements are likely to remain unaltered, according to Mandel. The administration is currently discussing the potential for changes to tuition and the timing of semesters, but has not yet announced changes and may not implement any.

Yesterday’s announcement is the culmination of an extended deliberative process on how to adjust the academic calendar in light of the COVID-19 pandemic and the possibility of a remote fall and/or spring semester. Until several days ago, a leading option under consideration by the administration was either a trimester or three-semester system that would split the academic year into three terms, potentially with students choosing which terms to attend and potentially with a summer 2021 term. Over the past week, following significant faculty feedback, Mandel and senior staff decided to retain the current two-semester calendar.

The reasoning behind the decision

Ultimately, Mandel found that lowering academic requirements to three courses per semester while maintaining two semesters fulfilled many of the same goals as trimesters or three semesters, particularly regarding reducing the burden of courses, with fewer disruptive drawbacks, including allowing students and faculty to take a summer break between academic years. “We went to the faculty meeting with that [three-term] idea because we very specifically wanted to hear what they thought about going from 32 to 30 credits, but in order to do that we had to put forward the three-semester option,” Mandel said.

To Mandel, reducing the number of courses to three was appealing in large part because of the difficulties that many students have faced with remote learning, as gleaned from a survey on remote learning that the administration sent out on May 1. “If we’re remote, it became clear that managing four classes, particularly when they’re asynchronous but even when they’re synchronous, was becoming very complicated for people,” she wrote. She pointed in particular to “the change of mode of learning, the fact that people were doing so much work sometimes broken into smaller groups, the way time is organized differently [and] the other burdens people have to deal with at home.”

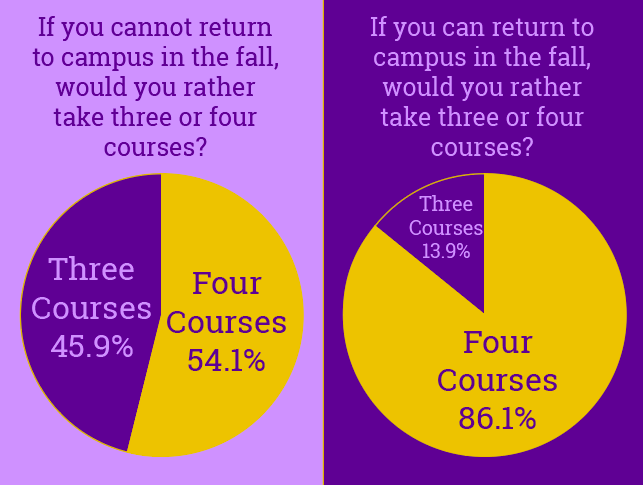

Even in the event that classes resume on-campus in the fall, Mandel believes that a reduction in the required number of courses will lower the number of classrooms in use and therefore assist in social distancing, even though students have the option to take four classes. In a Wednesday Record survey of approximately 550 non-seniors, which received 294 responses, 86 percent of respondents reported that, if the fall semester were on campus, they would prefer to take four classes rather than three. In contrast, if classes were off-campus, only 54 percent of students said that they would prefer to take four classes instead of three.

Mandel emphasized that some remote classes are likely to continue even if students return to campus, which may limit the number of classes that students want to take. “Twenty-five percent of our faculty are in an age bracket … that will give them pause about whether they want to be teaching in the classroom,” she said. “Others have family members or other circumstances that make it difficult for them. So students are going to have remote classes, whether we have some on-campus classes or not.”

The decision to remove Winter Study was driven in large part by the desire to have the same academic calendar whether classes are on- or off-campus and concerns over a potential winter resurgence of the virus. Mandel added that even if classes are on campus, being able to focus on logistics rather than classes in January will allow the administration “to assess what happened in the fall and prepare for the spring.”

Though Winter Study has been canceled, Mandel emphasized that no other decisions have been made regarding January, such as issues like athletic training.

How the administration arrived at this option

Holding two semesters rather than three may prove challenging, if not impossible, for students planning on taking a semester off in the fall and hoping to still graduate in four years.

In a Record survey sent to students last week, 68 percent of respondents said they would consider withdrawing for the fall if remote learning continued. The previously considered three-semester system would have allowed students to take the fall or the spring semester off and remain on-cycle, while it remains unclear how the two-semester model will fulfill those students’ needs.

Mandel explained that while the three-semester model was appealing for its flexibility, students and faculty pointed out to her that it would have left very little time for a break between the 2020-2021 and 2021-2022 academic years. “Imagine going through an intensive academic year at Williams and starting the next one 20 minutes later,” Mandel said. “I think none of us were really thinking about that.”

Mandel added that the ultimately adopted plan, which maintains two semesters, seemed the least disruptive to faculty and students as compared to a three-term plan.

Faculty feedback was ultimately the most impactful to Mandel, she said. “It was feedback from the faculty meeting … which made us realize there was an easier way to do what we were hoping to achieve with the three [semester] plan,” Mandel said. “I think what we learned about the various versions of the three [semester] plan was that it was making things hopelessly complicated, so we went to a system which would be simpler to understand and simpler to implement.”

In the faculty meeting on the trimester and three-semester plans, numerous faculty raised concerns that focused in large part around course requirements and scheduling. Chair of Mathematics and Statistics Richard de Veaux expressed relief that the administration decided against a three-term plan. “I am very relieved that the trimester system is off the table,” he said. “I had already raised logistic[al] issues at the faculty meeting that pointed out the problems that departments with scaffolded courses like Math with 130, 140, 150 and languages would have with the trimester system.” Multiple departments expressed concern that what de Veaux refers to as “scaffolded courses,” or courses that are sequential in nature and are only offered in a chronological order, could have been hampered by a three-term system.

Professor of Chinese Chris Nugent, who is also Chair of the CPC, expressed similar sentiments. “A three-term structure would introduce different challenges [to Chinese], such as deciding in which terms to offer the two halves of a year-long course or how to repeat parts of courses to allow all students who so desired to take these courses,” he said. “Because all units at the College have designed their curricula around our usual two-semester structure, I think we were confident that sticking to this would be the most fair option across the board and introduce the fewest unexpected challenges.”

Committee chair perspectives

Many faculty members provided input that led to the current model, including the chairs of the FSC, CPC, CEA and Honor and Discipline Committee.

“I felt it important that students, to the greatest extent possible, be able to take the courses they want to take,” Nugent wrote in an email to the Record. “I believe the model we ultimately chose will accomplish this goal better than the other models we considered.” Nugent added that he appreciated the plan for its ability to allow students to focus more on fewer classes, and for its relative lack of complexity when compared with the other models being considered.

“Because all units at the College have designed their curricula around our usual two-semester structure, I think we were confident that sticking to this would be the most fair option across the board and introduce the fewest unexpected challenges,” Nugent said.

Chair of the Honor and Discipline committee and Professor of History Gretchen Long also appreciated how the three classes per semester model could take some pressure off students. “I would like a system [where], if we are remote, professors give more lower stakes assignments than usual. I think assigning some group work would be good. Faculty will need to be really explicit about what students are allowed to access and use as they complete assignments,” she wrote in an email to the Record.

“I would like to make sure we have ways for students to reach out to faculty and deans when they are floundering and/or panicked,” continued Long. “ We will have to find a way to foster and encourage a sense of academic community so that students commit to upholding the standards of that community.”

Student perspectives

The email released yesterday detailing the changes was sent to all current students, faculty, staff and emeriti, and was posted on the College website, according to Chief Communications Officer Jim Reische.

Over the past several weeks, students have provided input through a survey on remote learning and a comment form available on the College website. Mandel also weighed surveys conducted by the Record and plans for the administration to release more student surveys in the future. She will also hold open office hours this coming Friday.

In the Record survey sent Wednesday, 44 percent of students approved of the way that the administration communicated with students regarding changes to the academic calendar and course requirements. 36 percent expressed disapproval and 19 percent said they felt neutrally.

Though slightly more students approved than disapproved overall, disapproving students were more likely to leave comments on the survey. Among students who did disapprove, many felt that the email contained less information than previous administration communications.

“I am honestly really disappointed at how blindsided I was by this,” Aliya Klein ’22 said regarding the communication of the news. “I felt like the school was [previously] being really transparent with us about options for next year, and it made me (and I’d imagine others) feel like we had an ability to rationalize what might happen next year and evaluate our options.”

“While I understand that it’s a tough situation for everyone (students, staff, and administration), I wish that the email updates contained more than the bare minimum,” Kayla Han ’22 said.

“I think that the main issue with this plan is that it comes to us at a time when we have almost no other information on how the next semester will look,” said Yannick Davidson ’23. “While I understand wanting to give people quick answers, I think that this plan made things more confusing in an already confusing time.”

Student reactions to the changes themselves were also mixed. In the same survey, 45 percent of students disapproved of the changes to requirements and the calendar, while 23 percent approved and 32 percent were neutral.

“One concern I have is what graduate schools/other institutions may think regarding a student’s choice to take three classes when they may take three or four,” said Peter Hollander ’21. “As someone who is applying to graduate school next year, I definitely feel pressured to take four classes, even if I’m allowed to take three, out of fear that schools would see my application as less competitive.”

“Personally, I don’t think the reduced minimum of courses per semester will affect me much, since I’m a single major,” said Richard Gonzalez ’22. “My main concerns are everyone’s safety, and the experiences of marginalized people on campus, especially incoming students.”

For Mandel, the issue of inequity cited by Gonzalez would have been a potential concern under any of the proposed plans for the upcoming academic year. “The global crisis we’re facing affects us in inequitable ways, and that has been really evident from the beginning of the crisis, depending on who you are and your background,” Mandel said.

For her, allowing for students to take three classes was the best way to accomodate students in difficult circumstances while providing maximum choice to a range of students. “The reduction from [four to three] courses as an option, not a requirement, provides room for people who are navigating really challenging circumstances to do what they need to do,” she said. Giving students this choice, she said, is meant to “provid[e] the educational pathways that work for you given your own personal circumstances.”

Next steps

In the coming weeks and months, departments will have to deliberate on how the reductions in required courses could alter major requirements, among other logistical concerns. “I am hopeful that it will not impact the requirements for Math or Stat,” De Veaux said. “I would hate for a math or stat major to mean something different for a few Williams classes. But we have not decided anything yet.”

A new curricular planning working group, announced in Mandel’s email yesterday, will begin to deliberate on the effects of this new policy and conduct outreach to students and faculty in the coming weeks to inform their future decision-making. The group will “develop plans for implementing this approach if we’re unable to hold in-person classes in Fall 2020 or Spring 2021,” Mandel wrote in her email.

The new working group contains professors, staff and two students: Gabby Martin ’21 and Onder Kilinc ’23. “My goals are to represent the problems that arise from our diverse student body to the best of my ability,” Kilinc wrote in an email to the Record. “I think there are a vast variety of challenges which include trying to anticipate student response (e.g taking three or four classes) and ensuring that divisional and major credits are suitable for this new system while still upholding academic reputation.”

Co-chair of the new working group and Professor of Psychology Safa Zaki expressed her hope that their plan will allow the College to “continue to provide students with a true Williams education.”

“Our aim is to develop a plan that reflects the creativity, vibrancy, and resilience of the Williams curriculum, in case we have to conduct the fall semester remotely,” wrote working group co-chair and Professor of Classics Edan Dekel. “By incorporating a broad range of expertise and perspectives, we hope that our work will reflect the core values of the Williams community.”