“It’s like Christmas, but I’m stuck in my house and my degree got cut short,” Caroline Fairweather ’20 said in a video on her Instagram story, referring to the boxes of art supplies that she and her classmates received in the mail to complete coursework for THEA/ARTS 201: Worldbuilding for Theatre. Fairweather showed off the goods: a cutting board, colored pencils, multiple varieties of paper and measuring tools, an Exacto knife and adhesive materials. “It’s like I have the design studio in miniature,” she said.

The class, which is required for the theatre major, is a studio course filled with hands-on projects in different aspects of “worldbuilding”: researching and creating costume, set and light models and abstract evocative art pieces. It is one of the many courses in the theatre, art, music and dance departments undergoing changes during the switch to online learning.

THEA 206: Directing for the Stage previously consisted of in-person projects each week where students would stage and direct scenes with other students as actors. Now, the class focuses on analyzing the work of prominent directors and the preparation process of directing a play, shifting more into theory than practice. Meanwhile, the tutorial THEA 255: Performing Shakespeare has eliminated writing and scenes between partners and is instead prioritizing individual performance and increasing the number of soliloquies that students will present to the class.

THEA 256: The Expressive Body, a movement training class exploring the body as an instrument of expression, was drastically reinvented to focus on weekly asynchronous guided videos. “So much of the work was about developing an awareness of other bodies in space and collaborating on live performance compositions with others,” Assistant Professor of Theatre Shanti Pillai said. “As a group we have it clear for ourselves that the class is not as it was and there is no pretense that it can be. However, it has been fulfilling in a new way. ”

While all professors are finding new ways to make their courses fulfilling, there is concern for what will be missing from virtual arts classes. “There are many, many aspects of an education in theater that can be done with a decent video connection, design supplies at home, reading and discussing and writing, but at some point, we need to be able to put people together in a room to make art,” said Associate Professor of Theatre David Gürçay-Morris ’96, who teaches Worldbuilding for Theatre and chairs the theatre department.

As with Worldbuilding for Theatre, students in ARTS 241: Introduction to Oil Painting also received shipments of art supplies to complete their coursework. But Professor of Art Laylah Ali ’91 did not include any oil paint at all; rather, the class focus has switched to acrylics because oil paints have flammable properties and not all students have proper ventilation.

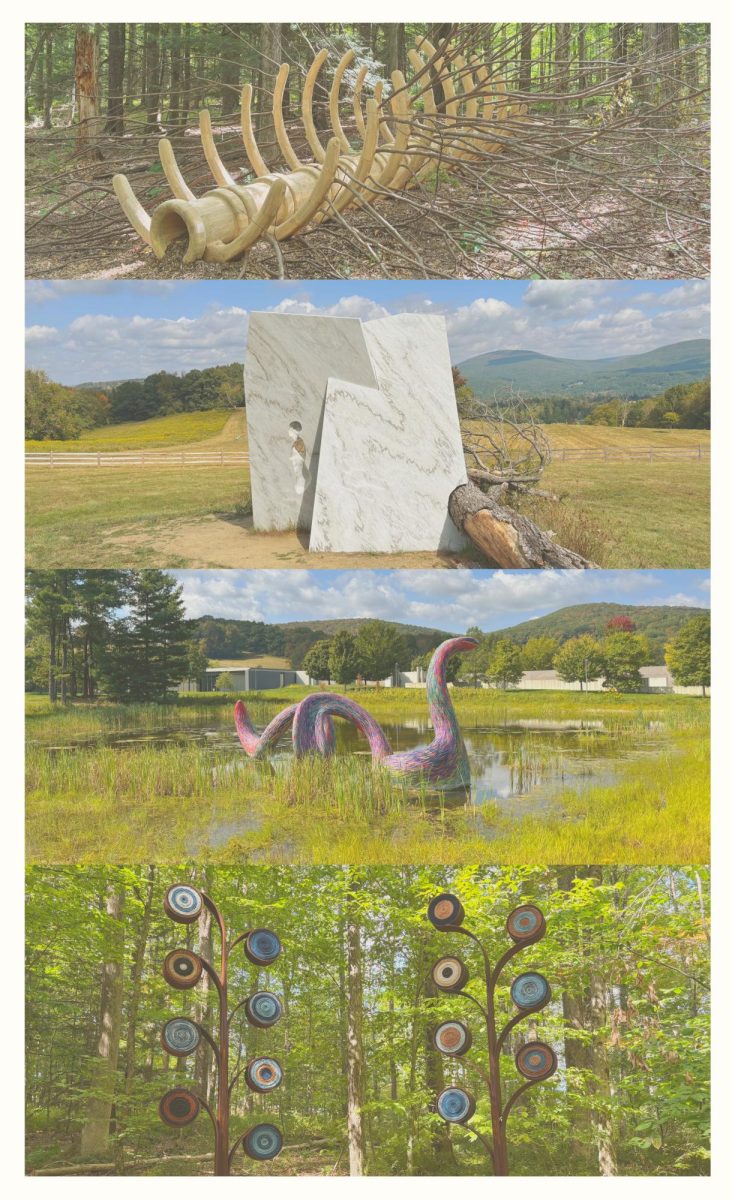

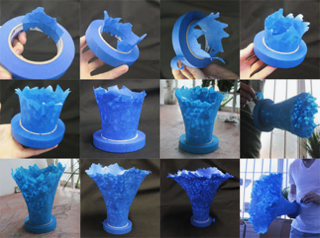

Not all art professors could mail their students supplies. During the last class of ARTS 275: Sculpture, students cut out steel sheets using the new plasma cutter in the science shop. Because students do not have access to welders and other necessary tools at home, this project remains unfinished. Professor of Art Amy Podmore has encouraged her students to “try and embrace our new limitations as a way of sparking potential overlooked areas of creativity.” Before leaving, she gave each student a roll of blue painter’s tape to “create an interesting sculptural form/interaction with this material.”

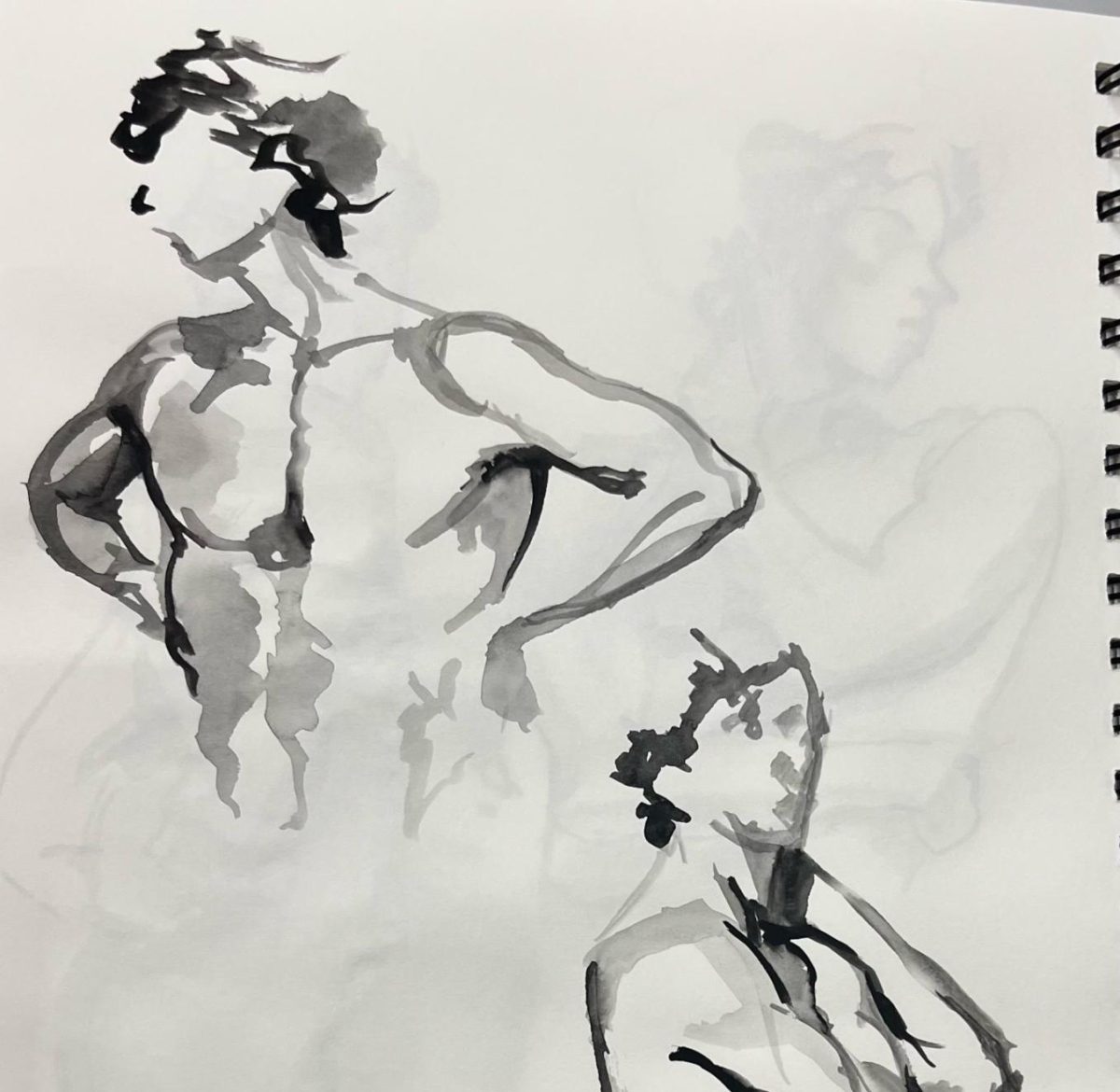

Some classes have created digital portfolios to showcase their work. Podmore’s sculpture class and both of Ali’s classes, Introduction to Oil Painting and Arts 100: Drawing I, have private Instagram accounts where all students can log on, share their work and maintain a connection despite the different time zones and locations.

Drawing I has moved from a studio course to asynchronous audio lectures. “I was initially super shocked about that, because in my head, studio art is a very visual medium,” Nicolle Mac Williams ’21.5 said. “Then I thought about the class, and something she told us early on about how there is no right way to do it, and there’s not one goal that you should be aspiring towards, and then it totally clicked and made sense to not be able to see anything.”

Mac Williams added that she appreciates the extra time that remote learning gives her to build skill and create art for herself with less pressure. “I’m very lucky that I can fully devote myself to this work in a way that I don’t think I would have been able to on campus,” she said.

But for others, having extra time can be an uncomfortable change. THEA 201, Fairweather said, “is designed to really put you under a lot of time pressure. Now, it’s strange, because in one way, it’s a benefit that there’s more time, but I think that’s also one of the pillars of the class: to make you do work so fast, throw it together, and push yourself to the edge of what you think you can do. That’s really when exciting stuff happens.”

On campus, many studio classes assign projects for homework and devote the bulk of the class period to giving each other feedback, such as ARTS 220: Architectural Design I, where formalized presentations and critiques were an important aspect of the class.

“It will probably be hard to recreate that level of collaboration,” Gavin McGough ’22 said. “The process has not been eliminated, but it has definitely changed… It will be more focused on what you can scrap together… what your core weird, raw, undeveloped idea is.” Similar to Podmore’s sculpture class, Senior Lecturer in Art Ben Benedict encouraged his students to work with their home materials and surroundings. Their first assignment was to analyze a building based on concepts discussed earlier in the semester.

“One student analyzed a house down the street from where she is staying in Arizona that she really dislikes,” Benedict said. “It was terrific.” From student feedback, he instituted a regular Building of the Week discussion where students can follow and share their personal curiosity and research.

Music professors have also adapted their approaches to giving students feedback. Every music major is required to take at least two semesters of private lessons during their time at the College. Most of these lessons have now shifted away from learning new music due to lags in online video calling and are focusing on strengthening general technique and skill.

“It’s going to be more of my responsibility to take that music and practice it in my own time using the exercises that my voice teacher has taught me instead of doing the songs in the lessons themselves,” Chris Van Liew ’23 said.

The same sentiment applies for his music class, MUS 104: Music Theory and Musicianship, the second half of a yearlong course required for the major. “Music theory isn’t a class that can be crammed in a night, especially aural skills,” he said. “Those take time for your brain to adjust to.”

On campus, the class met every day with alternating lectures, discussions, creative work, live music analysis, aural skills and keyboard labs. “Having a physical piano there in the room was necessary for literally every single day, but now not everybody has access to a piano,” Van Liew said. The keyboard labs have been cancelled for the rest of the semester and other live aspects have been replaced by online annotation software.

Assistant Professor of Music Zachary Wadsworth, who teaches the course, agreed that the biggest aspect missing with the transition to online learning is the lack of shared space and personal feedback.

“I’m trying to be as available to my students as possible — live through Zoom, in chat spaces, or over email,” he said. “I value the deeply personal nature of education at Williams more than almost anything else, so I’ve been trying my hardest to make sure my students feel that I’m still ‘there,’ even if we’re on opposite sides of the planet.”

Another professor making an effort to be available to students is Artist-in-Residence in Dance Janine Parker. She initially wanted to hold classes synchronously to mimic the studio experience with real-time feedback, but this was made impossible by her students’ differing time zones. Parker switched her classes to filmed videos for her students to follow along to, which she said was “not the most ‘optimal’ choice on one hand, but the most equal choice on the other hand.”

She has her students send videos of themselves doing exercises that they’re struggling with as well as exercises they think they’ve improved on. She sends responses to supplement the feedback necessary for improvement in dance technique.

Alex Bernstein ’23, a student in Parker’s class DANC 304: Ballet III, said that the biggest challenge is the transition from dancing in a studio to her bedroom. “It just feels wrong to not be able to separate my spaces into a dance studio, a workspace, a bedroom and a place where I eat. Now it’s all the same,” Bernstein said. Despite having to dance in small and unconventional spaces, Parker has encouraged her students to dance as “fully” as they can.

Bernstein is also taking DANC 217: Moving While Black, which was formerly held in Greylock for easy and spontaneous access to the dance studios. “We would sometimes forego our actual classroom with desks and chairs and spend our entire period in the studio just experimenting with ideas from our readings and putting them into action,” Bernstein said.

Bernstein is also in four dance groups that have been staying in touch through team bonding and Zoom dance parties, but none are formally training. Similarly, Van Liew is in two choirs that are continuing to stay connected but can no longer make live music together.

Additionally, many performance theses had to be canceled or drastically altered, including Fairweather’s, which was an original play she had devised, written and was directing as a full production, working with actors and a team of designers. The cast performed a semi-staged reading of the play the weekend before she left.

Wadsworth also works with seniors on music theses. “The hardest thing for me, personally, has been trying to help guide my senior students through the last month,” he said. “I was a student during 9/11 and the 2008 recession, but I never lost the experiences that these students have now lost. So the biggest challenge, really, has been to try to help my students grieve, recover, and imagine their futures in a world that will be different from the one we have known.”

Across disciplines, professors have been emailing their students with suggestions for online arts streaming services and digital workshops, as professional artists are also grappling with similar questions of how to make collaborative art in isolation.

“We need to be really rethinking what we mean by ‘together’ or ‘in a room,’ and all the things about communication and process and experience that go along with that,” Gürçay-Morris said.

Students expressed similar sentiments. “To dance is to be a part of a community,” Bernstein said, “and online, you don’t really get that energy.”

“There’s a camaraderie that happens between the people in the class when you’re staying up all night together in the ’62 Center that I think will be missed,” Fairweather said.

Despite this, professors are inspired by the work of art-makers as a global community. “Artists have always embraced uncertainty and been good conveyors, reflectors and community builders in stressful times,” Podmore said.

Wadsworth echoed this idea, saying, “In times like these, I think we need the alchemy that art can provide, where beauty can emerge from emotions like uncertainty, fear and loneliness.”