Over spring break, as students adjusted to the reality of the pandemic and prepared to make the best of the latter half of the semester, I received an email from my English professor linking to a Guardian article about World Poetry Day. In the piece, poet Mary Jen Chan reflects how the current pandemic has driven her to return to some of her favorite poems. She writes, “Now more than ever, I turn to poetry for its propensity towards truth, its tensile strength and its insistence that language can, and must be, the bridge that connects us all during these difficult times.”

This ethos – one I have heard countless times in classes at the College – is not new, especially to those who have devoted their lives (or really any significant portion of their time) to literature. In a moment that offers the ultimate test to the written word’s ability to connect us, members of the College community have rallied to keep it afloat.

Despite time differences, health concerns and daily worries, students and faculty have found ways to share and discuss favorite pieces of literature, whether it be over social media or in one-on-one exchanges. Many professors reported that they had recently emailed short texts or poems out to those in their classes, in hopes of offering some sort of communal solace in this lonely time.

The student-run Novel Teas book club has also moved online, where students continue to discuss each month’s selections as they do on campus. In order to ensure all club members have access to the books amidst library closures, the group’s leaders are encouraging them to take advantage of audiobooks and other virtual options.

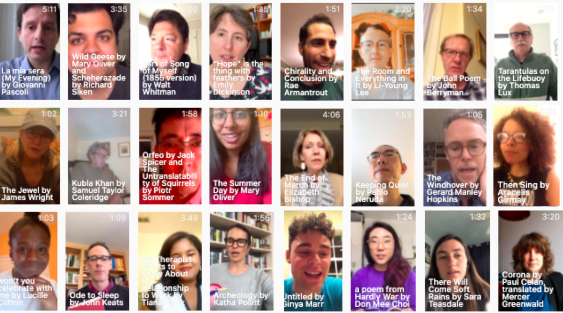

On social media, professors in the College’s English department are sharing their favorite poems in a series of Instagram videos called “poems & passages.” Assistant Professor of English Ianna Hawkins Owen started the project by reading “Then Sing” by Aracelis Girmay and, in the weeks since, has recruited 25 other faculty members and students to read poems that are meaningful to them.

Owen, who noted that she has used poetry as a means of communication with friends since high school, launched the project in March after most students left campus. “I thought with everyone being dispersed, having students be able to see our faces might communicate that we still want to reach out and connect,” she said.

In each post, someone shares a favorite poem in an intimate, selfie-style video filmed in their home. Some feature the English language’s most well-known poets, such as Emily Dickinson or John Keats, while others offer up new, often unrecognized voices. In his video, AJ Chabot ’21 shared “Untitled,” a piece written by his best friend Ginya Marr ’21. Former Associate Director of the Davis Center Tatiana McInnis read “My Therapist Wants to Know About My Relationship to Work,” by Tiana Clark, a friend of hers from graduate school.

The page’s uploads have garnered hundreds of views from students and alums, who often leave comments expressing their excitement over seeing familiar and long-missed faces. On Associate Professor of English Bernie Rhie’s reading of “Keeping Quiet” by Pablo Neruda, an alum from the Class of 2010 wrote, “You are one of my very favorite professors and hearing your voice is bringing me so much joy!”

Similar academic communities have followed suit. The College’s astronomy department recently shared a poem to its Instagram account for National Poetry Month. Duke’s English department also launched a similar series of videos, crediting Owen and her department with the idea.

Others in the College community have cemented connections with friends and loved ones through literature in a host of different, creative ways. Professor of English and Chair of American Studies Cassandra Cleghorn began a visual journal exchange with a friend in Chicago. Cleghorn, who shared part of her visual journal in one of the department’s Instagram videos, first began the journal after seeing a pair of writers in Italy exchanging daily postcards.

Every few days, Cleghorn makes an entry, which often include some portions of poetry or prose. The pages of her journal are colorful and free flowing, without rigid structure or requirements. It has provided a needed break from the constant stream of distressing news, she said. “For the first two or three weeks of the self-sequester, I was unable to even think about writing or formulating any kind of a response to the moment,” she explained. “Then, slowly, I began to feel the need to make something, to be creative.”

Cleghorn has found herself drawn to poems that have long been meaningful to her, including Melvin Dixon’s “Spring Cleaning,” written during the AIDS crisis of the 1990s and Alan Dugan’s “Winter: For an Untenable Situation.”

“These may not seem like particularly uplifting poems,” she said. “I don’t go to poetry for uplift, exactly. I am taking great sustenance from poets who pay tender attention to their lives. Poets happen to be really good at describing isolation, longing, fear, small joys in small things. These poems of acute noticing help me get through the day.”

In asking professors about what literature they are consuming while isolated at home, I expected to receive many recommendations of ways to escape from this hard-to-swallow global reality: classic fantasy novels or ethically questionable but cosmetically pleasing travel memoirs. What I kept getting, however, were pieces that, rather than distract them, helped them process and grapple with the current pandemic.

Professor of English Jim Shepard captured this succinctly with his recommendation of “anything that helps them think.” Others, such as Professor of English Stephen Tifft, were more specific, citing examples of literature produced in historical periods of disease outbreaks, including, “for the most exact parallel to our present situation, albeit from 300 years ago, Daniel Defoe’s funny and incisive A Journal of the Plague Year.”

For Professor of English Bernie Rhie, exactly what he is reading has become less important than the connection to others it brings. Rhie, who runs a weekly meditation group in Thompson Chapel, transitioned the group to an online format, launching a podcast called “Intro to Zen Online.” He has produced almost 20 episodes in the weeks since the cancellation of in-person classes. In each, he leads listeners through meditation exercises and offers some words of reflection or parts of written work.

During this bizarre and unforeseen period, he said, the connections offered through his teaching feel especially meaningful.

“The thing I love most is that connection,” he said. “That’s where my emphasis is, it’s much less on the object or what we’re reading. It’s ‘Is the thing we’re reading going to sustain conversations?’ Right now, that’s what I want to read for.”