From April 4–7, the Africana studies department celebrated and commemorated 50 years of Africana studies at the College, collectively remembering the individuals and movements that shaped and continue to shape the lives of Black students on campus today. Throughout the weekend, alums, community members and former faculty were invited back to campus to take part in a sequence of events that current students could attend as well.

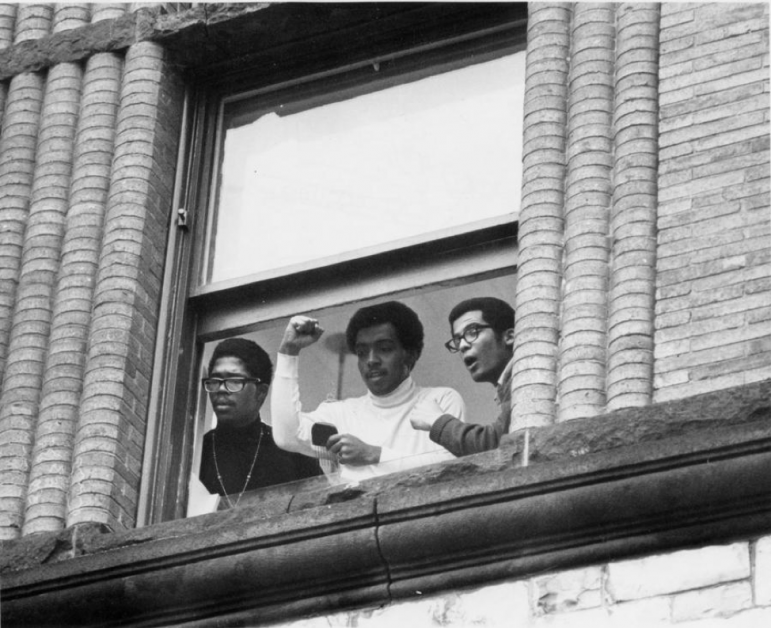

In March 1969, the Afro-American Society (AAS), which is now the Black Student Union (BSU), published a list of 15 demands that included establishing an Afro-American studies program, hiring additional Black faculty and creating a Black cultural center in which Black students could live. A month later, dissatisfied with the administration’s response to their demands, 34 students from the Afro-American Society occupied Hopkins Hall at 4 a.m. on Friday, April 5. The students remained there until the following Tuesday, when opposing parties reached an accord that detailed the tangible steps to be taken by the administration to meet students’ demands.

The occupation was a culmination of many nationwide tensions and movements, compounded by frustrations felt by many Black students at the College due to the lack of administrative support for their demands. Not only did it follow the decades-long struggles of the civil rights movements and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., but the occupation took place during a wave of student activism at peer institutions. Just a year prior to the occupation, San Francisco State established the department of Black studies following the longest campuswide strike in U.S. history, which lasted for five months. Additionally, two months before the Hopkins occupation, Black students at Wesleyan took over Fisk Hall to prompt the establishment of African American studies as a department, not a program.

The importance and significance of celebrating 50 years of Africana studies was echoed by alums who returned to campus for the anniversary. “At my high school, this guy who I used to play basketball with, comes and says to me that ‘the great grandson of Jay Gould, one of the robber barons of America, said that African American people, people of African descent are inferior because they have no culture, no history, no civilization.’ I asked, ‘What did the teacher say?’ My friend said, ‘The teacher fumbled.’ Since then, I started doing research, but I had nobody to guide me. This was in 1968 during the civil rights movement,” said Vernon Manley ’72, one of the 34 occupants of Hopkins Hall, on why an Africana studies program was not only important, but necessary.

“During the Hopkins takeover, people like this guy [Clifford Robinson ’70] and Preston Washington ’70 were negotiating with the College and organizing and looking to try to do something, bringing professors and other people of African descent to the community that could expand on knowledge of people of African descent was amazing, and I was looking forward to that. Participating in that takeover was not an option. I didn’t care, I was willing to risk losing my financial aid,” Manley said. “So it’s a phenomenal thing to have what is now called Africana studies.”

The remembrance of 50 years of Africana studies is a dual mission. Associate Professor of Africana Studies Rhon Manigault-Bryant, curator of the “For Such A Time As This” exhibition at Special Collections and organizer of the weekend, explained how Africana 50 was both a celebration and a commemoration.

“It is not a small feat – it really isn’t. It is a tremendous thing to have been around for half a century,” Manigault-Bryant said. “But there’s also a commemoration aspect because that road has not been easy. There are literally people who fought tooth and nail with this institution, to try and make sure that there’s room for me and my colleagues to do the work that we do.

“It is both thrilling and humbling, and it’s also an important reminder. We really feel like we have the onus to live up to those expectations, and that commemorative side is really important because that’s the part that reminds us [to] keep our feet to the fire, to hold ourselves accountable, hold our students accountable and hold Williams accountable.”

Manigault-Bryant also spoke of the high turnout among alumns at the events. With approximately 70 alums, as well as their guests, participating in the events that took place over the weekend, the discussions and the stories encompassed a variety of lived experiences.

One of the events that took place over the weekend was a symposium of three consecutive panels with former and current students, faculty and community members who reflected on their time at the College and beyond. Panelists included Bobette Reed Kahn ’73, who was the first Black woman to graduate from the College, Khalil Abdullah ’72 and Professor of English D.L. Smith.

Todd Hall ’16, former co-chair of the BSU, emphasized the value of listening to the diverse experiences at the College. “I felt awestruck listening to the Eileen Julien, Assistant Dean at Williams from 1975 to 1978,” he said. “She discussed how flatly her peers dismissed issuing an anti-discrimination statement [in reference to gay and lesbian sexuality] — they said they could not even discuss it. I marveled at how she continued to advocate for students and taught for three years, despite attempts in hiring discrimination only blocked by intervention from then-President Oakley.”

Robin Powell Mandjes ’82, one of the panelists at the symposium, also shared similar sentiments about the weekend.

“While I had met a number of alumni from the early 70s in the past, I had never heard their stories told in such a substantive way. And by hearing their stories, I appreciated my Williams experience even more,” she said. “I appreciated what alumni had done before me to make my student experience a rich one.”

Students were also able to draw connections between alums narratives and their experiences today. Olaide Adejobi ’19, secretary of the BSU and a panelist at the symposium, spoke about the cyclical and iterative nature of student activism and its demands. “Hearing what the original organizers of the Hopkins Hall occupation had to say about their time at Williams is so resonant with what students experience today, and that was a really powerful reminder and that was definitely something that came up a lot during the weekend,” she said. “It was a powerful reminder of how things really are static and dynamic.”

The celebration also included walking tours. “Not A Onetime Event: Echoes of the Hopkins Occupation” was organized by public humanities fellows and drew on the history of student activism to emphasize the existence of unmet demands and the tactics used by the College to stall and repress student demands.

“In my own research, I found a stunningly, almost comically, common theme: committees. It seems Williams College makes a Committee for almost everything and anything it doesn’t want to have to answer to,” said Emma York ’19, a public humanities fellow, on her research on anti-apartheid activists who fought for the College to divest from South Africa in the 1970s and 1980s, and the hunger strike that followed it. “This pseudo-commitment to meeting the needs of a diverse – and quickly diversifying – student body contributes to activist fatigue and relies, again, on the unacknowledged, uncompensated labor of PoCs, minorities and more.”

BSU also organized a town hall on saturday, which strived to look forward and engage alumni in tackling unmet demands.

Rocky Douglas ’19, one of the co-chairs of the BSU, and Shane Beard ’20, MinCo representative and community outreach coordinator, commented on some of the discussions from the town hall meeting. “I sincerely hope that in the next 50 years there will be more support for departments like Africana, that there is an Asian American studies department, that those are both majors, that there is different representation for ideas like Indigenous studies, in our curriculum,” Beard said. “And that we’re finally ADA compliant, and that we are actually respecting and prioritizing the safety of survivors on campus. There are so many different things that people have been fighting for a while, that we’re still not there yet,” Douglas added.

Additionally, the BSU Town Hall centered around the need for affinity housing – which was one of the 15 demands of 1969 (“A case for affinity housing: Why the College should reconsider the housing system” by Alia Richardson ’19, Nov 14 2018) – and the conversations around free speech on campus that could inflict violence against marginalized people.

“What’s been so frustrating about the conversation about free speech right now is that it’s presupposing that the best thing to do to challenge ideas that dispose of the humanities of marginalized people is to debate it, which is to say that it’s like you go into the discussion with the premise that what the opponent is saying is true, that being, you are not human,” Beard explained. “What’s so frustrating is the idea that the College is supposed to be a safe home for everyone. It’s a residential college. If this is supposed to be a home, you can’t have a home that’s also hostile. Those two ideas don’t work with one another. It’s real violence.”

“This would be different if it was just intellectual. But this is about our livelihoods, this is 24/7. I have to eat lunch in the same place as these people, and go to class with these people, and sleep in the same space as these people,” Douglas said on the inconsistency between the celebration of the Hopkins occupation, while validating the ideas and dangers that could come with allowing speakers that denounce the humanity of marginalized identities.

Similar sentiments were shared by alums as well. Julien, former assistant dean of the college and director of the Institute of Advanced Study and Professor of Comparative Literature, French and Italian and African Studies at Indiana University commented, “We want benchmarks, but we really want also a change in disposition … we need to create the terms of our community, the terms within which we interact with one another.

“Our society cannot last with the kinds of enormous tensions and, you know, the sense of having been wronged, the psychological violences, and I say that because white students, the majority students, have to be convinced that it is in our welfare that it is in their welfare that everyone feels like they have a fair chance, that they’re heard, that they have opportunity, so that we can all contribute to create the kind of place where we can achieve and be fruitful and be productive and be fully human.”

Clifford Robinson ’70, one of the founding members of the Williams Afro-American Society and the leading organizers of the occupation, remained hopeful about the next 50 years. “There’s been so much change since we started here, and it’s worth remembering that,” he said.“Williams is going to always have to adapt to change. Change is going to come fast furious, in the next few years, even more than what we went through.”

Students and professors also expressed their wishes for the future. “Because I believe in the idea of freedom dreams and we have to dream of the impossible to get anywhere closer to where we want to be, my dream is that in the next 50 years, Williams is a campus where people don’t have to go to drastic means such as an occupation, or releasing demands, or a die-in, or a hunger strike, or two professors taking leave, to make social change,” Douglas said.

“Thinking about the future, thinking about 50 years from now, would be that Williams could be a place, and would be a place, and will be a place where folks of African descent, in particular but not exclusively, feel like Williams is really a place for them, feel like it’s a place where they can learn all kinds of things, including and especially about themselves, and how to navigate their existence in the world. I want Williams to be a space that can equip people to feel that way, think that way and create that way and contribute in that way,” Manigault-Bryant said.

Editor’s note: This article was updated at 4 p.m. on April 10 to add context to a quote from Todd Hall ’16 and at 3:47 p.m. on April 11 to add the names of the men pictured in the photo: Richard Jefferson ’70, Preston Washington ’70 and Michael Douglass ’71.