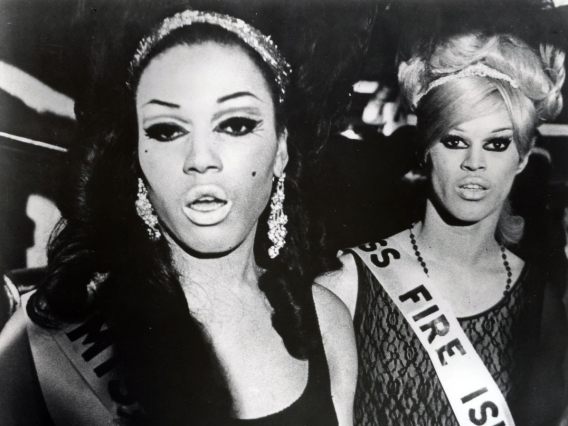

Miss Manhattan (Crystal LaBeija), left, and Miss Fire Island, right, compete in the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant in Frank Simon’s The Queen.

On Saturday evening, in anticipation of my invitation to the First Chance senior dance, I showered, shampooed and conditioned my hair, blow-dried my hair, applied anti-perspirant, covered a zit on my chin with “It Cosmetics Medium Tan Color Correcting Cream” (advertised on the tube as “Your Skin, But Better™”), squeezed my bust into a dress I’d bought from Goodwill the weekend prior, adjusted my bust so that less cleavage showed, readjusted my bust so that more cleavage showed, swooped eyeliner across my lids, fluffed my lashes with mascara, readjusted my bust so that less cleavage showed again, put in earrings, glossed my lips, shadowed my eyes, strapped myself into a pair of four-inch red velvet heels and tottered out of my dorm room into the November chill.

Femininity, if you want to “get it right,” is work. This was one of the largest takeaways from The Queen, a 1968 documentary screening at Images last week that I had the pleasure of seeing with Professor of Russian Julie Cassiday. The Queen, directed by Frank Simon, follows the participants of the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant (held at New York City’s Town Hall) as they prepare and perform in drag. Though The Queen premiered in 1968, it has rarely been shown in theatres since.

Thanks to a new restoration this past June, however, and thanks to the Davis Center, who partially sponsored the screenings at Images, The Queen has returned to the silver screen. “I imagine that when the film came out in 1968, it was just as shocking for the fact that it was about drag queens as it was this behind-the-scenes display of all the labor that goes into femininity at a beauty contest,” said Cassiday. “The fact that we’re dealing with men who are dressing up in drag makes it totally explicit that to be adequately feminine, to perform femininity, it is a ton of work… the taping, the pain, the gestures, the movements — that’s just as revolutionary as the drag element.”

Unlike certain documentaries, The Queen features no “talking heads” who comment on and historicize the action of the film. And unlike RuPaul’s Drag Race, there are no reality TV “confessionals” where queens offer up snark and throw shade. Rather, The Queen is 68 minutes of raw footage spliced together without any overdubs or attempts on behalf of Simon to guide the narrative toward a distinct interpretation. Simon’s camerawork creates an atmosphere of intimacy between the viewer and the subject. While viewers familiar with RuPaul’s Drag Race observe queens throwing shade and getting into fights, The Queen shows frank conversations about being gay in the South, being blacklisted from the military due to queerness and whether or not to consider sex reassignment surgery.

There are historical explanations behind the intimate aesthetics of the film: At the time The Queen was made, both drag and “homosexual relations” were illegal in New York State, meaning the queens featured in the film were shown engaging in criminal activity when in drag. Cassiday commented on the difference between the visual politics for drag queens before and after the 1969 Stonewall Uprising that catalyzed the LGBTQ+ Rights Movement as we know it today. “If RuPaul is Mama Ru, these are the great-grandmas — RuPaul got his start in the late 1970s, early 80s — and I think there’s a huge difference between the visual regime of the drag race and what [The Queen] is,” said Cassiday. “RuPaul’s Drag Race has been on for 10 years at least, it’s in an era after we’ve all seen reality TV, and everyone has a functional video camera in their phone, which means we’re super aware that everyone’s performing even when we’re ‘backstage.’ I don’t think that’s the case in 1967.”

That’s not to say these people don’t have performative elements of who they are — choosing to become a drag queen, that’s a given.” continued Cassiday, “But behind-the-stage for them actually was behind the stage, to a much greater extent than it can ever be now. Anyone who goes on drag race knows that you don’t only need costumes for when you’re performing, but you need to have them for when you’re in work mode. Here, that’s not the case.”

The time period when The Queen was set not only affected the aesthetics of its production, but the aesthetic standards that the queens themselves strive toward. “One of the great things about showing this film now is that the standards of femininity which these men were so exquisitely expressing are actually different from what we have in 2019,” said Cassiday. “These drag queens show you that it’s not only the hard work that goes into [performing femininity], but the time and place. Where do you learn that from? Who’s teaching you?”

Cassiday’s own research involves investigating standards of femininity in post-Soviet Russia, and specifically investigating the benefits and detriments of performing the labor of femininity. “As transgressive as being a drag queen was in the United States in 1967, these men are basically beating women at the game and raising the bar for beauty standards,” explained Cassiday. “In my own research, one thing I found in post-Soviet drag is that high-end professional drag queens… set the standards for women, and show women that femininity is labor, and this is how hard you have to work.”

The standards of beauty that the queens in The Queen adhere to closely mirror standards for women in 1967 — while queens of color feature in the film, the winning queen (Miss Harlow from Philadelphia) is a thin, plump-faced androgynous looking man who bears no small resemblance to Edie Sedgewick, Andy Warhol’s superstar and the “It Girl” of 1965 who was a staple of New York’s artistic scene. Cassiday explained that the queens in the film place a high emphasis on being “fishy” — a drag term meaning “able to pass convincingly for a biological woman,” derived (crudely, hilariously) from the supposed scent of a woman’s vagina. “Depending on the place and time there are different types of drag, different drag cultures,” explained Cassiday. “From what I know about beauty standards in the 1960s, the drag in The Queen is pretty conventional. We don’t see any totally queer drag queens. There’s no Conchita Wurst [the Austrian drag queen who won the Eurovision song contest in 2014, who performs in a crystal studded evening gown, long tresses, and full beard and mustache] here. So, something that goes really genderqueer — these queens aren’t interested in that, and the ones in post-Soviet Russia aren’t really either.”

Miss Harlow’s victory at the end, however, is a pyrrhic one — the most memorable scene in the film depicts Crystal LaBeija, a queen of color who placed fourth in the pageant, claiming that the contest was fixed for Harlow’s victory, and firmly stating her belief in her own beauty despite the refusal of the judges to recognize it. Shortly after the 1967 Miss All-America Camp Beauty Pageant, Crystal LaBeija hosted a ball for Black queens, and in the early 1970s, founded the House of LaBeija, which became a prominent drag house in New York. “Houses” serve as alternative families for primarily Black and Latinx gay and gender non-conforming youth who often must leave the homes they were raised in due to prejudice and violence — house culture is explored in depth in the iconic 1990 documentary Paris is Burning, and is fictionalized dramatically in Pose, a TV series created in 2018 by producer Ryan Murphy (of Glee and American Horror Story).

House culture also gave rise to vogueing, a dance form popular in many contemporary drag dance routines. While Crystal’s frustrations were only briefly documented in The Queen, the House culture that arose as a response to these frustrations prioritized the experiences of queer folks of color, and led to more media representations of these experiences, capturing what The Queen scratched the surface of.

The Queen is thus a keystone in a genre that continues to define itself in the face of dominant heterosexual historiography. “The Archive for Queer Culture in general tends to be really thin, since [queerness] has been so taboo for so long,” explained Cassiday towards the end of our time together. “Furthermore, the Archive tends to focus on medical records, since being queer or homosexual was pathologized, or police records, people getting reeled in and arrested, so having things in the archive that are queer culture generated by queer people is super valuable. This is the tip of an iceberg of human experience that was happening for people all over the U.S. throughout the 60s and 70s, and how little of that lives on. This definitely represents a chunk in the archive, but also a queer approach to history — if you stick with traditional historiographic approaches, you always end up privileging people with power — the literate, the people who can afford to leave the traces of who they’ve been behind — and other people get erased. You have to go beyond traditional methods of combing historical records and archives, and that’s why something like this is so valuable.”

“Box Office Hours” is a Record film discussion series with faculty, staff or community members who specialize in particular aspects of films showing at Images. For those interested in taking part in this series, please contact [email protected] or [email protected].