This past July, Professor of Astronomy Jay Pasachoff embarked on an astronomical expedition to Chile with Johnny Inoue ’20, Christian Lockwood ’20 and Erin Meadors ’20 to study and observe the July 2 total eclipse.

Supported by a grant awarded to Pasachoff last May from the Solar Terrestrial Program of the Atmospheric and Geosciences Division of the National Science Foundation (NSF), the group built upon Pasachoff’s successful research of other eclipses, most notably the great American eclipse of August 2018.

Preparation for the expedition, according to Pasachoff, began months in advance of the eclipse, as expensive equipment, including various telescopes and cameras, had to be shipped to the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory about 50 miles outside La Serena, Chile.

On the day of the eclipse, the team split up and coordinated their research over three different sites. Pasachoff, Inoue and Lockwood were stationed on the center line of the eclipse, positioned such that they witnessed the longest duration of totality, at 2 minutes and 35 seconds. Meadors was on duty in the city of La Serena itself, witnessing a duration of totality of 2 minutes and 5 seconds. The third and final observational unit was stationed at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, and included solar astronomer Kevin Reardon ’92.

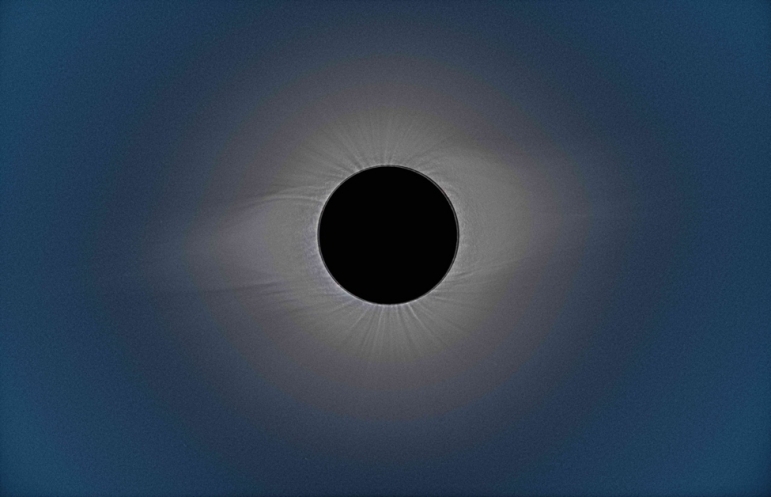

One of the principal goals of Pasachoff’s research is to track how the sun’s corona changes over the course of the sun’s 11-year-long sunspot cycle. At the moment, the sun is at the minimum of the cycle, meaning that very few spots can be observed on most days. As a result, the sun’s corona could be seen extending at the sun’s equator during the eclipse. Away from the equator, however, huge plumes of gas could be observed, held in place by the sun’s magnetic field.

Pasachoff hopes that, by consolidating the dozens of pictures of the corona that his team captured during the eclipse into a singular composite photo, he might be able to gain some insight into how the sun’s magnetic field changes along with the sunspot cycle.

In a similar vein, Pasachoff said he would like to use the data gained from the latest expedition in collaboration with Predictive Science Inc., a company based in San Diego. Predictive Science used measurements of the sun’s magnetic field months before the July eclipse in order to predict what the corona would be like during the event.

By providing Predictive Science with photos of the corona during the total eclipse, Pasachoff hopes to allow the company to compare its predictions with the hard data, and make subsequent modifications to its model for maximum accuracy — a worthy goal, according to Pasachoff, as the proper functioning of Predictive Science’s model will allow us to more accurately study how not just the sun shines, but also the billions of other stars in the universe that we cannot observe.

Pasachoff hopes to continue using the NSF funding to study the next two observable total eclipses, which will take place in December 2020 and December 2021 in Argentina and Antarctica, respectively. He also plans to travel to India this December and next June to observe two separate annular eclipses.

For students who are fascinated by eclipses, or simply wish to learn more about astronomy in general, Pasachoff recommends stopping by the observation deck on top of the Physics building on Nov. 11 in order to witness a transit of the planet Mercury. “It will look like just a dot,” Pasachoff said, “but it will be intellectually spectacular.”