Early 1970s: Fraternities head north

April 7, 2000

The College officially phased out fraternities in the 1960s after years of student discontent with some fraternities’ racist and anti-Semitic rushing practices, as former President John W. Chandler chronicled in The Rise and Fall of Fraternities at Williams College (2014). The College eventually persuaded the fraternities to give up their houses, many of which became upperclass dorms like Perry, Tyler, and Wood.

Backed by alums, underground fraternities emerged immediately after the ban was put in place, recalled Peter K. Frost, professor emeritus of history and former associate dean.

“At the time, I was a quite young member of the faculty and the youngest faculty member serving temporarily in the Dean’s Office,” Frost recalled. “I liked to joke that I was a mouse learning to be a rat. Despite that, when I asked students about their non-academic life at Williams, they seemed perfectly willing to tell me that there was something frat-like across the border in Vermont.”

Archival documents and interviews with alums confirm Frost’s recollections. A Record article from 1971 reported that four fraternities — TDX, Kappa Alpha (KA), Zeta Psi (ZP), and Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) — remained active.

“Currently both TDX and KA have between 25 and 40 members, while Zeta Psi appears to be between 10 and 20,” the Record reported. “DKE has one official member, [and] two honorary members (Villa St. Pierre who is houseman at Brooks and Sacred Sonny Beckwith, a skull, the last remains of a DKE Civil War fatality with tunnel vision.)”

DKE apparently faded away soon after, and according to the website of the national fraternity of ZP, the College’s ZP chapter closed in 1972. But TDX and KA were more tenacious.

Archived memos from the Dean’s Office reveal that the deans tried to keep tabs on the fraternities’ activities. They were well aware that TDX and KA owned houses in Pownal.

Although students lived in these houses, in at least some cases alums owned the properties. In 1970, Garret Schenck ’53 worked with a broker to find TDX’s Pownal house, correspondence in the TDX national archives shows, and TDX alums told the Record this year that Schenck was the one to buy the house. A TDX newsletter from 1970 reported that the national TDX organization helped finance the $33,000 sale (equivalent to about $220,000 today). Five TDX students could live there, with rents cheaper than the cost of Williams dorms.

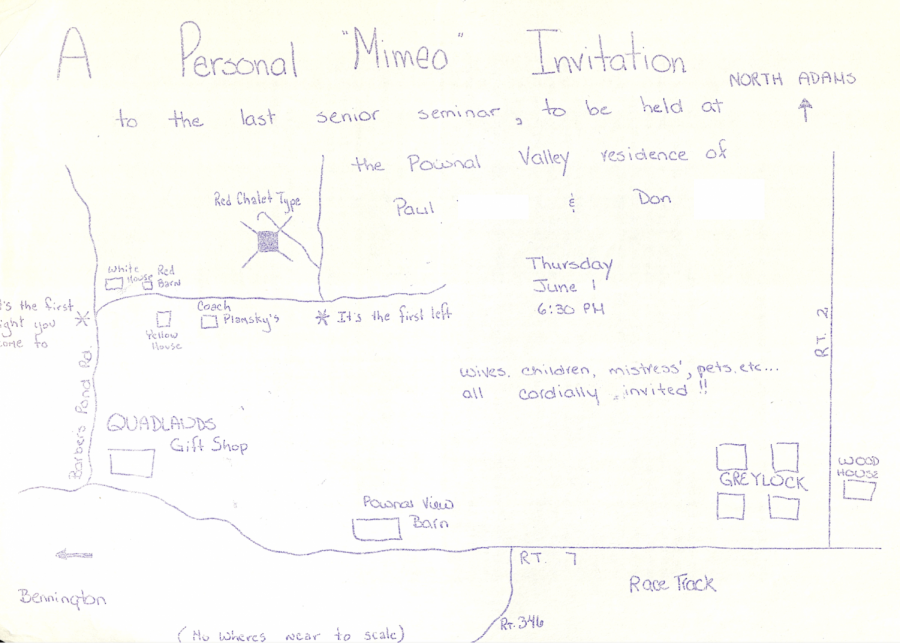

Among the deans’ files was a spring 1972 invitation to a “senior seminar” at TDX’s house in Pownal. The invitation — which included a “No Wheres near to scale” map of directions to the house — stressed that “wives, children, mistress’, pets, etc.” were “all cordially invited!!”

Also among those whom the TDX men cordially invited was Frost, who was then an associate dean. “This suggests a certain boldness in revealing the whereabouts of a frat,” Frost wrote at the time to the dean of the College.

The fraternity once invited President Jack Sawyer, whose administration had banned fraternities, to a Homecoming party in Pownal, a 1974 Berkshire Eagle article reported years after it happened. Sawyer apparently declined.

“We weren’t secretive,” TDX member Rob Pasco ’71 recalled to the Record. “We would kind of boast about it. We were kind of in the face of the College.”

The Record reported in 1971 that TDX was by far the least secretive of the fraternities, whereas some of the others kept a lower profile and had “security that makes the CIA look amateurish.”

“Membership in all four fraternities seems to be based on a personal referral system, where each member may invite a sophomore or upperclass acquaintance to join,” the Record reported. “It seems that freshmen are avoided, and the result is a large proportion of upperclassmen.”

Fraternities offered fellowship at a time when the College’s revamped housing system did not. Articles and opinion pieces in the Record complained that the dorms, though designed to replace the social aspects of fraternities, felt less like cohesive groups and more like mere places to live.

Fraternities helped fill that void, Pasco said. The TDX of the early 1970s was mostly about socializing; there were no secret handshakes or rituals.

“It was very, very welcoming, and very non-threatening, and obviously lots of fun,” said Peter Hopkins, a TDX member who was in the Class of 1974 before he withdrew from the College in his junior year. “It was a great way to get away from the academic pressures that everybody was under.”

Keeping the Partridge trust out of the College’s hands was part of what motivated alums to stay involved with the chapter. “The money had been one of the reasons that Theta Delta Chi had kept going,” Pasco said. “Because the alumni who didn’t like the College kicking them out, who didn’t like the College policy on that, didn’t want the College to get the money. So they put a lot of energy into it.” But undergraduates cared little about the Partridge money.

Though women were often invited to parties at the Pownal house, TDX did not admit them as members. Pasco said he decided to live in the house in part because his friend group in Hopkins House got split up when four women (some of the first at the College) moved onto his floor. Later, as a teacher, Pasco would become a strong supporter of coeducation. But as an undergraduate who had always been in all-male educational settings, he said, he felt “awkward” about living next to women.

Although the College had phased out fraternities in part because of their exclusivity, alums of 1970s-era TDX stressed that being in the fraternity was about meeting different kinds of people; they were not motivated by a desire to discriminate, they said. “We weren’t doing the same thing fraternities did before,” Kevin Austin ’70 said. “We were doing it so we could see different groups of people. Whereas, to me, the old-fashioned fraternity is only people who are like you and they don’t have anything to do with anyone else.”

TDX was mostly white — but, Pasco noted, so was Williams at the time. There was at least one member of color, a 1970 graduate. And according to the Berkshire Eagle, the fraternity apparently tried to recruit two Black men in 1973. The two men declined, however, because “they didn’t think they’d fit in,” the Eagle reported.

Administrators seemed to know who was in TDX, according to Pasco, but they took no disciplinary action against them. Still, Pasco recalled that at graduation, where he was wearing his TDX pin, President Sawyer handed him his diploma without shaking his hand.

The information available about KA is much more limited than that about TDX. In The Spirit of Kappa Alpha (1993), Robert S. Tarleton wrote that the KA house in Pownal was for “meeting and social purposes only.” He recounted that the College’s anti-fraternity stance seemingly increased student interest in KA.

“Initially, college heavy-handedness actually increased undergraduate enrollment for the Society in a ‘Christians in the catacombs’ response,” he wrote.

The underground fraternities seemed like just another extracurricular activity, Wendy Wilkins Hopkins ’72 recalled. She did not know much about them until several months after she graduated, when her now-husband Peter Hopkins moved into the TDX house.

“But in terms of my undergraduate experience, secret fraternities were not even a ripple,” she said. “You knew that they existed, but I couldn’t name anyone who would have been in one.”