How frats persisted for decades after they were banned

April 7, 2021

The story of the College’s underground fraternities began in the early morning of May 6, 1912, when successful Boston lawyer Olcott Osborn Partridge, Class of 1894, died by suicide. As a student, he had made his mark on the College. According to Olcott Osborn Partridge and the Partridge Trust (2002) by Bill McClung ’66, Partridge was valedictorian, editor of the yearbook, and class poet. But it was Partridge’s will, much more than his death, that would have an enduring effect on his alma mater.

Although Partridge left the bulk of his money to his mother, he also set aside a trust of $1,280.98 — equivalent to a little under $35,000 today — intended for the Williams chapter of Theta Delta Chi (TDX), his fraternity. Yet there was a strange catch. The Williams chapter would not get the money until 20 years after the death of the last member of the chapter, undergraduate or alum, who was alive at the time of Partridge’s death. If, after these years had passed, the TDX chapter no longer existed, the money would instead be split between the national TDX organization and the College.

It remains a mystery why Partridge included a clause that would prevent the money from being used for such a long time. Regardless of the reason, it had an unintended effect decades later. The College’s decision to phase out fraternities in the 1960s angered many alums, including a few diehard TDX members. If the chapter faded away, the College would receive a good amount of money — by 1970, the trust had grown to $67,508.35 (around $457,600 in today’s dollars). A few TDX alums wanted not only to preserve the fraternity they loved but also to stop money from going to the college that had tried to kill it.

So they did what they could to keep TDX alive. After the College banned fraternities, these alums funded some of the undergraduates’ underground activities (everything from parties to a speaker series) and even bought the chapter a five-acre property in nearby Pownal, Vt. In part as a result of their efforts, an underground TDX chapter managed to survive through the late 1980s — but not long enough to secure the money in the Partridge trust.

While its story was especially dramatic, TDX was not the only fraternity to continue operating in spite of College rules. Williams views itself as a pioneer for having banned fraternities in the 1960s, well before peer colleges like Middlebury and Bowdoin followed suit. But the College’s rules did not make fraternities disappear.

Based on research in College and fraternity archives, as well as interviews with several alums and former administrators, the Record has traced several threads of post-1970 fraternity activity. From the relocation of fraternities to Vermont, to the emergence of a fraternity-like club in the 1980s, to the existence of a secret fraternity through perhaps the present day, it is clear that fraternities persisted for decades after the College banned them.

Early 1970s: Fraternities head north

The College officially phased out fraternities in the 1960s after years of student discontent with some fraternities’ racist and anti-Semitic rushing practices, as former President John W. Chandler chronicled in The Rise and Fall of Fraternities at Williams College (2014). The College eventually persuaded the fraternities to give up their houses, many of which became upperclass dorms like Perry, Tyler, and Wood.

Backed by alums, underground fraternities emerged immediately after the ban was put in place, recalled Peter K. Frost, professor emeritus of history and former associate dean.

“At the time, I was a quite young member of the faculty and the youngest faculty member serving temporarily in the Dean’s Office,” Frost recalled. “I liked to joke that I was a mouse learning to be a rat. Despite that, when I asked students about their non-academic life at Williams, they seemed perfectly willing to tell me that there was something frat-like across the border in Vermont.”

Archival documents and interviews with alums confirm Frost’s recollections. A Record article from 1971 reported that four fraternities — TDX, Kappa Alpha (KA), Zeta Psi (ZP), and Delta Kappa Epsilon (DKE) — remained active.

“Currently both TDX and KA have between 25 and 40 members, while Zeta Psi appears to be between 10 and 20,” the Record reported. “DKE has one official member, [and] two honorary members (Villa St. Pierre who is houseman at Brooks and Sacred Sonny Beckwith, a skull, the last remains of a DKE Civil War fatality with tunnel vision.)”

DKE apparently faded away soon after, and according to the website of the national fraternity of ZP, the College’s ZP chapter closed in 1972. But TDX and KA were more tenacious.

Archived memos from the Dean’s Office reveal that the deans tried to keep tabs on the fraternities’ activities. They were well aware that TDX and KA owned houses in Pownal.

Although students lived in these houses, in at least some cases alums owned the properties. In 1970, Garret Schenck ’53 worked with a broker to find TDX’s Pownal house, correspondence in the TDX national archives shows, and TDX alums told the Record this year that Schenck was the one to buy the house. A TDX newsletter from 1970 reported that the national TDX organization helped finance the $33,000 sale (equivalent to about $220,000 today). Five TDX students could live there, with rents cheaper than the cost of Williams dorms.

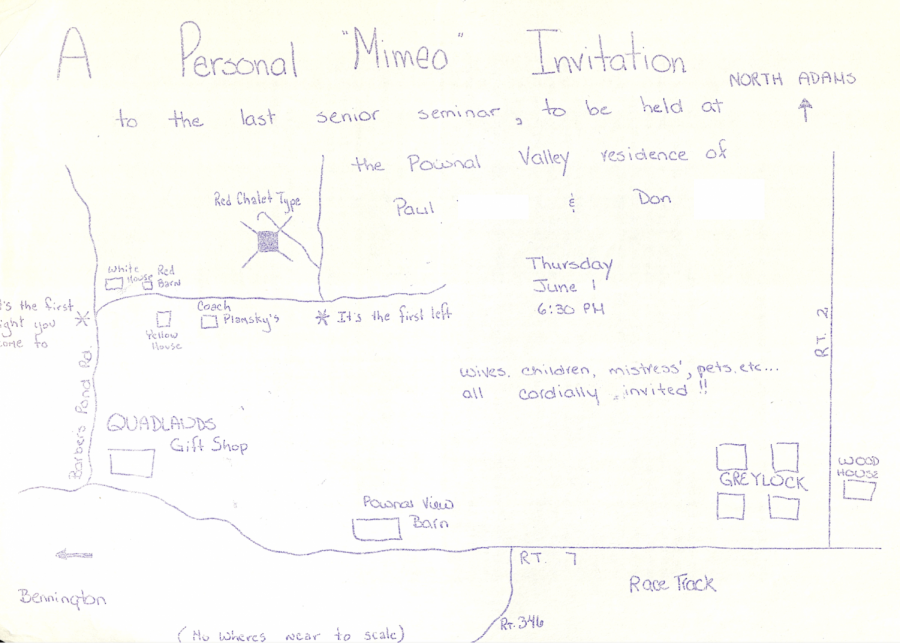

Among the deans’ files was a spring 1972 invitation to a “senior seminar” at TDX’s house in Pownal. The invitation — which included a “No Wheres near to scale” map of directions to the house — stressed that “wives, children, mistress’, pets, etc.” were “all cordially invited!!”

Also among those whom the TDX men cordially invited was Frost, who was then an associate dean. “This suggests a certain boldness in revealing the whereabouts of a frat,” Frost wrote at the time to the dean of the College.

The fraternity once invited President Jack Sawyer, whose administration had banned fraternities, to a Homecoming party in Pownal, a 1974 Berkshire Eagle article reported years after it happened. Sawyer apparently declined.

“We weren’t secretive,” TDX member Rob Pasco ’71 recalled to the Record. “We would kind of boast about it. We were kind of in the face of the College.”

The Record reported in 1971 that TDX was by far the least secretive of the fraternities, whereas some of the others kept a lower profile and had “security that makes the CIA look amateurish.”

“Membership in all four fraternities seems to be based on a personal referral system, where each member may invite a sophomore or upperclass acquaintance to join,” the Record reported. “It seems that freshmen are avoided, and the result is a large proportion of upperclassmen.”

Fraternities offered fellowship at a time when the College’s revamped housing system did not. Articles and opinion pieces in the Record complained that the dorms, though designed to replace the social aspects of fraternities, felt less like cohesive groups and more like mere places to live.

Fraternities helped fill that void, Pasco said. The TDX of the early 1970s was mostly about socializing; there were no secret handshakes or rituals.

“It was very, very welcoming, and very non-threatening, and obviously lots of fun,” said Peter Hopkins, a TDX member who was in the Class of 1974 before he withdrew from the College in his junior year. “It was a great way to get away from the academic pressures that everybody was under.”

Keeping the Partridge trust out of the College’s hands was part of what motivated alums to stay involved with the chapter. “The money had been one of the reasons that Theta Delta Chi had kept going,” Pasco said. “Because the alumni who didn’t like the College kicking them out, who didn’t like the College policy on that, didn’t want the College to get the money. So they put a lot of energy into it.” But undergraduates cared little about the Partridge money.

Though women were often invited to parties at the Pownal house, TDX did not admit them as members. Pasco said he decided to live in the house in part because his friend group in Hopkins House got split up when four women (some of the first at the College) moved onto his floor. Later, as a teacher, Pasco would become a strong supporter of coeducation. But as an undergraduate who had always been in all-male educational settings, he said, he felt “awkward” about living next to women.

Although the College had phased out fraternities in part because of their exclusivity, alums of 1970s-era TDX stressed that being in the fraternity was about meeting different kinds of people; they were not motivated by a desire to discriminate, they said. “We weren’t doing the same thing fraternities did before,” Kevin Austin ’70 said. “We were doing it so we could see different groups of people. Whereas, to me, the old-fashioned fraternity is only people who are like you and they don’t have anything to do with anyone else.”

TDX was mostly white — but, Pasco noted, so was Williams at the time. There was at least one member of color, a 1970 graduate. And according to the Berkshire Eagle, the fraternity apparently tried to recruit two Black men in 1973. The two men declined, however, because “they didn’t think they’d fit in,” the Eagle reported.

Administrators seemed to know who was in TDX, according to Pasco, but they took no disciplinary action against them. Still, Pasco recalled that at graduation, where he was wearing his TDX pin, President Sawyer handed him his diploma without shaking his hand.

The information available about KA is much more limited than that about TDX. In The Spirit of Kappa Alpha (1993), Robert S. Tarleton wrote that the KA house in Pownal was for “meeting and social purposes only.” He recounted that the College’s anti-fraternity stance seemingly increased student interest in KA.

“Initially, college heavy-handedness actually increased undergraduate enrollment for the Society in a ‘Christians in the catacombs’ response,” he wrote.

The underground fraternities seemed like just another extracurricular activity, Wendy Wilkins Hopkins ’72 recalled. She did not know much about them until several months after she graduated, when her now-husband Peter Hopkins moved into the TDX house.

“But in terms of my undergraduate experience, secret fraternities were not even a ripple,” she said. “You knew that they existed, but I couldn’t name anyone who would have been in one.”

Late 1970s: Adelphic Literary Society tries its luck

As some fraternities established themselves in Pownal, Alpha Delta Phi (AD), which had disappeared in the 1960s, reemerged in the spring of 1976 in its old domain of Perry House. At least 24 students signed a letter to the fraternity’s international leadership requesting recognition for the “Adelphic Literary Society of Williamstown” (abbreviated “ALS”), what would essentially be an AD chapter. AD International accepted the request, and 15 students joined the ALS that May.

AD International then stepped in to vouch for the fledgling fraternity. In July of 1976, AD leadership met with representatives from the College — President Chandler, the treasurer, the dean of the College, the director of development, and a trustee — at the Williams Club in New York City. AD International asked the College to grant amnesty to the students in the ALS, hinting that it otherwise would bring legal action on First Amendment grounds.

The College leaders refused. As a private institution, they argued, the College had the ability to regulate its own residential life.

“Personally, I am mystified as to why you don’t spend your time, energy and resources on places where you are wanted rather than on Williams where you are not,” Director of Development Willard Dickerson ’40 sniffed in a letter to the president of AD International two weeks after the meeting at the Williams Club.

The Record learned in September 1976 about the ALS’ attempt to establish itself on campus. One cause for concern among the administration, it noted, was that “five of the fraternities whose property was taken over by Williams when fraternities were banned have ‘reverter clauses’ in their agreements such that, if fraternities return to Williams, their former property will revert to them.” In other words, if the College let one fraternity exist, it would have to give up some of the former fraternity houses it now owned. (At least two of these reverter clauses expired in the early 1980s, according to deeds and tax documents obtained by the Record last year.)

Peter Berek, dean of the College at the time of the ALS controversy, said that he didn’t remember the reverter clauses’ being the primary driver of the Dean’s Office anti-fraternity stance. It was more that a return of fraternities would have weakened a vision of education that encompassed more than academics. With no fraternities, Berek said, the College now bore responsibility for the social, and not just intellectual, lives of students.

And in any case, the ALS was not the College’s most pressing concern. “It seemed more an episode of silliness than a major threat to the College,” Berek said.

“Personally, I am mystified as to why you don’t spend your time, energy and resources on places where you are wanted rather than on Williams where you are not.” —Director of Development Willard Dickerson ’40 to ALS International

The Board of Trustees nevertheless put out a statement in October 1976 reminding students of the ban on fraternities. Soon after, a letter to the Record from an official of AD International revealed that the ALS had dissolved itself.

Meanwhile, the TDX chapter was going strong. The spring 1977 newsletter sent to alums reported the induction of five members of the Class of 1979. It boldly listed the names of the 106 men who had been in the fraternity from 1970 through 1977, one of whom is now a College trustee and one of whom is now in the U.S. House of Representatives.

In a May 1977 letter to the Dean’s Office urging the College to take a firmer anti-fraternity stance, Tim Hester ’77 noted that there were three off-campus fraternities, which he estimated had a total of 100 members. He recommended that the College dissuade students from joining fraternities by reminding students of the reasons behind the ban.

Writing to the Record over four decades later, Hester said he had forgotten about the letter. He recalled, though, that the existence of fraternities was common knowledge when he was a student.

“I do not remember the names of the fraternities, but it was widely known on campus that there were active fraternities,” he wrote. “This was not viewed as a secret, and as my note reflected there was a lively social scene at various off-campus fraternities during these years.”

1980s: Club Bacchus emerges as actual frats falter

From its birth in 1983, Club Bacchus made clear that it was not a fraternity. It was “a social organization of athletically-oriented male students who enjoy getting together to socialize, to support Williams athletics, and to sponsor very successful all-campus parties,” as two members put it in a 1987 Record op-ed. It was, members insisted, about cheering on sports teams and throwing parties.

Paul Meeks ’85, a founding member of Club Bacchus and the one to give it its name, recently emphasized to the Record that the founders spoke to the deans early on about how to avoid the appearance of being a fraternity. Quoted in the Record in March 1983, Assistant Dean of Students Cris Roosenraad said, “I can’t imagine calling them a fraternity. A fraternity would include such things as residential pattern, exclusivity, where the members pick future members themselves, and a national tie-in.”

But with its all-male membership, reliance on dues, and party culture, Club Bacchus was in some respects fraternity-esque. In Record op-eds from the late 1980s, some female students criticized the club for what they described as a sexist atmosphere.

Meeks, who graduated a few years before these op-eds, recently told the Record that the club had no rules against admitting women; it ended up being all men because women chose not to join. “The guys flocked to it, athletic and otherwise,” he said. “The ladies, not so much.”

The men wore a uniform of white button-downs, dark ties, and blue jeans to club parties. Meeks said that the only entrance requirements were to chug one beer, sing a song of choice, and pay a fee.

Of the 18 men who appeared in issues of the Record from the 1980s as members of Club Bacchus, all but one were on the football, lacrosse, or ice hockey teams (and many were on a combination of the three). “We supported the teams — it was part of our M.O.,” Meeks said. “I think more of it was because we were supporting our friends and it was started by people on those teams. But there was no formal engagement with the football, lacrosse, or hockey team.”

Over the years, Club Bacchus acquired a reputation for troublemaking. College Council admonished the club in 1984 after some members threw tennis balls and beer cans on the ice at a Williams–Amherst ice hockey game. In fall 1986, Williamstown police responded to a Club Bacchus–sponsored party after a brawl broke out; the club’s president was charged with serving alcohol to minors, according to a Record article from the time. But after 1989, Club Bacchus disappeared from the pages of the Record.

A curious footnote to the Club Bacchus years emerged from the Record’s conversation with Meeks. Meeks said that he was not involved in the club after he graduated and that he does not know what happened to it. But he recalled that when he returned to campus for the retirement party of longtime head lacrosse coach Renzie Lamb, some undergraduates who said they were in Club Bacchus approached him, wanting to meet the man who gave the club its name.

“They heard it was me, and they wanted to come over and speak to me, I guess,” Meeks said.

Lamb’s retirement was in 2003, over a decade after the seeming demise of Club Bacchus.

At the same time that Club Bacchus was making Record headlines in the 1980s as a quasi-fraternity, some actual fraternities were winding down. The underground KA chapter came to an end in 1983, according to the national fraternity’s website. According to The Spirit of Kappa Alpha, “the recruiting difficulties of such a tenuous, unpublicized existence far from the mainstream of campus life began to hurt the chapter, and it closed quietly when the last of its undergraduate members graduated in the early 1980s.”

TDX managed to last a few more years than KA, though not without its own difficulties. It faced a crackdown from the deans in 1983, according to an April 1985 letter from Boine Johnson ’53, one of the alums most involved in supporting the underground chapter, to other TDX alums. Johnson claimed that the deans had threatened that “no fraternity men would receive their diplomas,” leading to “a wholesale resignation from Theta Delta Chi.”

As a result, the chapter faltered, even giving its charter up to the national fraternity. But Johnson expressed hope that the chapter would soon get its charter back. He declared his commitment to keeping the chapter alive — especially because Lawrence Woodard (Class of 1913), the last man standing between TDX and the Partridge money, had died the month before.

All the fraternity needed to do to get the money was to hang on for 20 more years.

In 1986, according to a memo from Johnson to TDX alums, Johnson met with then-Dean of the College (and current Professor of English) Stephen Fix to discuss TDX’s plans to reestablish itself. Per the memo, Fix told Johnson that in order to comply with College rules, an organization could not have a Greek-letter name and could not be secret or exclusive.

By 1987, correspondence in the national TDX archives shows, a group of undergraduates had established the Partridge Society — which pointedly did not carry a Greek-letter name. The Society had a membership of 10 in October 1987; it is unclear if it was secret and exclusive. Although at first not officially recognized by the fraternity, the students got the national organization of TDX to return the chapter’s charter.

“Last spring several members were threatened with expulsion if they did not resign their membership. We know of no current undergraduate members.” — The 1990 minutes of the national TDX organization

But in 1990, TDX’s national organization formally revoked the Williams chapter’s charter.

“No initiates or payments for 2-3 years,” read the minutes of the national organization’s meeting from that year. “Last spring several members were threatened with expulsion if they did not resign their membership. We know of no current undergraduate members.”

The chapter was 15 years away from realizing the money in the Partridge trust.

One fraternity that did not flounder in the 1980s was St. Anthony Hall. Although St. Anthony Hall has left much less of a public record than TDX or even KA, tax records obtained by the Record show that the fraternity’s graduate organization told the IRS in 1983 that it would “provide financial support for a college literary Society and may at a future time support an undergraduate fraternity chapter.”

Throughout the late 1980s, the Dean’s Office continued to hear reports from students of underground fraternity activity.

“We never proved anything,” Fix said. “We never caught anybody red-handed singing fraternity songs or wearing funny Greek letters.”

Still, he brought his concerns to the Board of Trustees. In 1989, the board reaffirmed its 1976 statement against fraternities and declared its “full support for the officers of the College in their efforts, disciplinary and otherwise, to insure that it is understood and adhered to in the Williams community.”

1990s through present: College’s fight against fraternities continues; St. Anthony comes to light, twice

In August 1992, according to an internal Dean’s Office memo, two students approached Fix, at the time the outgoing dean of the College, to express their concerns about underground fraternities.

“Their sense is that there are at least two fraternities — a smaller one which they think is loosely organized and a larger one involving an off campus house,” the memo reads. “The smaller one they think has disbanded.”

The students told the deans that they believed the larger fraternity was affiliated with Greek letters, though they didn’t know which ones. But a hand-scribbled note at the top of the memo reads “Delta Psi/St Anthony” (Delta Psi is another name for St. Anthony Hall).

Spurred to action by the two students’ account, Dean of the College Joan Edwards (now a professor of biology) sent a letter on Nov. 18, 1992, to all students reminding them of the College’s ban on fraternities.

“We will not hesitate to take significant disciplinary action — including suspension or expulsions — against students who are found to be participating in such organizations,” she wrote.

In its article about the letter the following week, the Record spoke to several anonymous students who said that underground fraternities existed. One junior said a fraternity had tried to recruit him in his first year. “You guys understand about the importance of the old-boy network, the importance of tradition at Williams, and how to have a good time,” he said a senior in the fraternity had told him.

Whether this fraternity was St. Anthony Hall or some other group is unclear. But in fall 2003, it emerged that a co-ed chapter of St. Anthony Hall had been operating since the 1970s. It called itself the Vermont Literary Society (VLS), the Record reported, and its members met weekly to “share literary works and personal experiences.”

The Record revealed that Jack Shaw ’62, a St. Anthony alum who at the time was the Pentagon’s deputy undersecretary for international technology security, had tried and failed to negotiate with the College to let the fraternity use its old “goat room” — i.e. meeting room — in what was by then the Center for Development Economics.

“By this time next year I plan to have the Lambda [Williams] Chapter’s presence quietly acknowledged and take possession of their marvelous [goat room],” he wrote in the spring/summer 2002 issue of the national fraternity’s publication. “This effort will not be bloodless and I anticipate opposition from a variety of quarters, but our flag will once again fly in Williamstown.”

The deans offered amnesty to any VLS members who came forward, but no one did. The revelations about the VLS exploded onto the pages of the Record’s opinions section, where some students decried the fraternity for its exclusivity.

“Williams is a society based upon a spirit of openness and tolerance and equal and fair opportunity, all under the aegis of common rules,” Ben Cronin ’05 wrote in an op-ed. “St. Anthony Hall, and any other secret frats that may be here, are by their very existence contrary to that spirit.”

Underground fraternities faded from the public view over the next several years. Then, last fall, a Record investigation pointed to evidence of the VLS’s continued existence, citing tax forms and references to the VLS on the website of the national St. Anthony Hall. The graduate organization of the College’s chapter of St. Anthony Hall, the 1853 Foundation, had been donating about $20,000 of its roughly $450,000 each year to the VLS for “research and educational purposes.” Alums who graduated as recently as 2016 were listed on tax forms as members of the 1853 Foundation.

The VLS has been defunct since August, however. And it remains to be seen whether the 1853 Foundation will continue to provide donations to a revived VLS or a similar organization now that the College is aware of its existence.

As for the Partridge trust: It finally matured in 2005, 20 years after the death of Woodard and almost a century after the death of Partridge. The money ultimately amounted to $1.4 million, split between the College and the national TDX organization, according to the College’s class notes from August 2005.

The underground chapter of TDX, which had once been sustained in part by the promise of getting the Partridge money, was by then long gone. Nevertheless, President Morty Schapiro invited TDX alums to Williamstown for a cocktail party to celebrate the release of the money from the trust.

Schapiro was “gracious as always,” said Bill Garth ’67 (who was once the president of the chapter’s alumni association), and at the party there was little sadness about the end of TDX. Older alums, by then dead, may have been more attached to fraternities. But Garth said he felt that the College had actually changed for the better, especially with its increased gender and racial diversity.

“The demise of fraternities was never a source of sadness or rancor in my class or those I knew that followed,” he recently told the Record. “It was a fellowship to enjoy in the Purple Valley, but never a passionate cause, at least not for me.”

If you have any information about underground fraternities, past or present, please email [email protected].