Ephraim Williams was an enslaver. What will the College do about it?

February 10, 2021

Ephraim Williams Jr., the original benefactor and namesake of the College, was an enslaver.

This is a clear-cut matter of historical fact. Documents from his life, including his will, demonstrate that he enslaved at least five Black people, named Prince, J. Romanoo, Moni, London, and Cloe. What is less clear-cut is what the College will do to address this fact.

Although it is not a new revelation — historians and students at the College have written about it for decades — the College has done little to reckon publicly with it. An interview in the summer 2016 edition of Williams Magazine makes reference to the often-overlooked portion of Ephraim Williams’ will that mentions the people he enslaved. Special Collections includes his buying and selling of enslaved people in its timeline of his life. Otherwise, the College’s website does not acknowledge the fact that its benefactor and namesake held at least five Black people in slavery.

That is likely to change, however. This academic year, the College’s Committee on Diversity and Community (CDC) is examining institutional history, with a focus on slavery and colonialism. One of its main charges is to figure out how to grapple with this history — including that of the College’s namesake.

The lives of Ephraim Williams and those he enslaved

Born in 1715 in Newton, Mass., Ephraim Williams Jr. became a soldier and land speculator like his father, Ephraim Williams Sr.

The younger Ephraim Williams moved to Stockbridge in roughly 1742. He served as a captain in King George’s War, a conflict in the 1740s that pitted England and the Iroquois Confederacy against France and the Wabanaki Confederacy. His troops were stationed in Fort Massachusetts, in what is now North Adams.

After a group of Indigenous men charged Fort Massachusetts, men under Williams’ command shot at them, pursued them, and eventually found one man who had been recently buried. Williams’ men dug him out of the ground and scalped him, according to a Boston Gazette article from May 1748.

Williams enslaved at least five people over the course of his life. One bill of sale shows that in 1750, Williams sold to his cousin Israel “a certain negro boy named Prince, aged about 9 years a servant for life.” In 1752, Williams purchased from his father three people being held in slavery: an adult named Moni, a boy named London, and a girl named Cloe, according to A History of Williams College (1917) by Leverett Wilson Spring and Ebony & Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities (2013) by Craig Steven Wilder, a historian at M.I.T. who taught at Williams from 1995 to 2002. A bill of sale from February 1755 states that Williams bought a “Negro boy named J. Romanoo aged about sixteen years.” Besides their names and ages, little else is known about those Williams enslaved.

At the time he bought Romanoo, Williams was serving as a major in the British army in the French and Indian War; he was promoted to colonel that March. In July 1755, about to embark on a dangerous military expedition to New York, Williams wrote his final will. He was killed by troops under French command at the Battle of Lake George two months later.

Williams’ will provided for “the support and maintenance of a free school” in what was then the town of West Hoosic, provided that “the Governour & General Court give the said township the name of Williamstown.” The Williamstown Free School opened in 1791 and became Williams College in 1793.

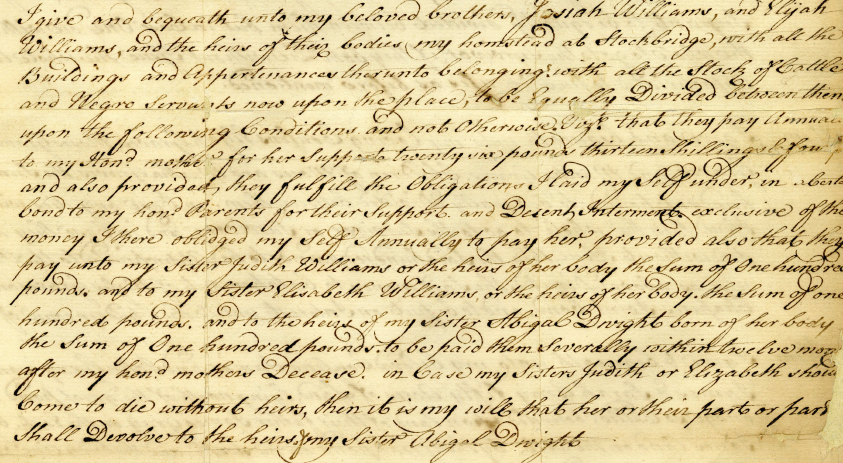

In that same will, Williams bequeathed the largest portion of his estate, including his homestead at Stockbridge, to his brothers Josiah and Elijah. He also left them his “Stock of Cattle and Negro Servants now upon the place, to be Equally Divided between them.” The will does not mention the names of these enslaved people — or as he described them, “Negro Servants” — or how many of them there were. There are no further known records of the fates of Moni, London, Cloe, and Romanoo, or of Prince, who had been sold to Israel Williams five years earlier.

In the mid-18th century, it was fairly common for wealthy white people in Massachusetts to be enslavers, though slavery was less widespread and less central to the economy than in the South. Between 1755 and 1764, according to an estimate cited on Mass.gov, roughly 2.2 percent of the total population of the colony were enslaved Black people. Slavery was legal in Massachusetts until 1783, when the Massachusetts Supreme Court effectively abolished it.

Slavery and the College

Selena Castro ’17 traced the establishment of the College to the stolen labor of the Black people Ephraim Williams enslaved in “the mountains! the mountains!: Slavery in Williamstown, MA,” a research paper written in 2015 for Chair and Professor of American Studies Dorothy Wang’s “Theories and Methods of American Studies” class.

“[I]f his ‘Negro servants’ provided labor in his household and on his land, then they had direct ties to the money that was used to purchase plots of land in what is now Williamstown, as well as to establish the free school, and consequently Williams College,” Castro wrote.

The College’s ties to slavery did not end with Ephraim Williams, who died decades before the College was founded. Benjamin Simonds, a founder of Williamstown and the College, enslaved a man named Ishmael Thomas and forced him to take Simonds’ place in the Continental Army in order to be freed, Ansari said. Simonds also enslaved a second man named Hartford, and possibly more. Amos Lawrence, namesake of Lawrence Hall, was a wealthy cotton merchant who thus profited from slavery, according to Kevin Murphy, the senior curator of American and European art at the Williams College Museum of Art.

Students at the College did start an anti-slavery society in 1823, the first of its kind in Massachusetts, according to Castro’s paper. But it ultimately advocated sending Black people to Africa rather than letting them live freely within the United States. Castro cites a letter the society wrote in 1826 that argues that “that it would be better for free people of color themselves, as well as for the country, if they were conveyed to the colonies in Africa.”

“Though efforts are made to improve the moral and intellectual condition of the few negroes among us, by affording the means of knowledge imparted in our daily and Sabbath schools; yet a greater proportion of them, compared with the white population, are yearly returned as convicts in our penitentiaries,” the letter reads.

Wang, who co-teaches “Uncovering Williams” with Murphy and has for years taught courses that deal with the College’s institutional history, said that the College should commission a report on its historical ties to slavery. “But more than a report, I want to see concrete steps taken today to address the racial inequality and the alienation and marginalization of students of color and faculty of color,” she said.

She pointed to the incidents described on the @blackatwilliams Instagram account and during the 2019 boycott of English courses as recent examples of racism that members of the College community have faced. She stressed that six BIPOC women have left the faculty in the last two years.

“You take the history, and you try to do better,” she said. “But you do it in a way that’s actually going to be concrete and material and not just the rhetoric of the diversity statement or another committee.”

A nationwide reckoning about colleges’ ties to slavery

In recent years, colleges across the country have faced questions about how they should account for the racism of their founding figures. How should racist benefactors, especially those who were enslavers, be remembered? Should universities pay reparations to those descended from enslaved people? Who gets a say in these decisions?

Georgetown University’s explicit connection to slavery came to public attention in 2016 after historians discovered that two former university presidents had orchestrated the sale of 272 enslaved Black people to pay off the institution’s debts in 1838. Soon after, the university established a working group to examine the institution’s ties to the slave trade and find ways to make amends. Georgetown eventually committed to raising $400,000 a year to pay reparations to the descendants of the 272 enslaved people.

Yale, meanwhile, has grappled with the legacy of its benefactor and namesake Elihu Yale, a British-American businessman who trafficked and sold enslaved people. Last June, far-right figures took to social media with the hashtag #CancelYale to mock progressives’ attempts to rename institutions. Others then co-opted the hashtag to demand seriously that administrators rename the university, a step that senior university staff has said it has no plans of taking.

Another controversy emerged at Yale in 2017 when students organized to protest the residential college named after pro-slavery Senator John C. Calhoun. After the protests garnered national attention, the administration renamed the college in honor of Navy Rear Admiral Grace Hopper, one of the preeminent computer scientists of the 20th century.

Most recently, in December, Johns Hopkins University released a statement acknowledging that its founder and namesake, who had long been heralded as an abolitionist, had in fact enslaved a number of people in the decades preceding the 1864 abolition of slavery in Maryland. The university has since joined the Universities Studying Slavery consortium, to which Georgetown, Yale, and over 70 other colleges — but not Williams — also belong.

What comes next for the College

Unlike with Johns Hopkins, the fact that Ephraim Williams was an enslaver has never been a secret. It comes up multiple times in both Ebony & Ivy by Wilder and Colonel Ephraim Williams: A Documentary Life (1970) by Wyllis E. Wright, Class of 1925. It is a large focus of Castro’s 2015 paper, which is housed in the College archives and has been cited in The Gritty Berkshires: A People’s History from the Hoosac Tunnel to Mass MoCA (2019) by Maynard Seider. And it is abundantly clear from primary sources.

Yet the College has never systematically addressed its connections to slavery. Whereas institutions like Brown and Princeton have commissioned reports about their historical links to slavery, the College has so far not done anything of the sort.

That may change now that the faculty, staff, and students on the CDC are spending this academic year addressing institutional history, especially the College’s historical ties to slavery and colonialism. Ephraim Williams’ history is just one of many areas of focus. The committee has also been examining the occupation of Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican homelands, the marginalization of Williamstown’s Black residents, and alums’ role in the colonization of Hawai‘i, among other topics.

“Even if we’re not a part of it or we don’t represent the identity group that did do this stuff, I think it’s important to recognize that we all hold privilege by being in this institution,” CDC Co-chair Essence Perry ’22 said. “There has to be some reckoning that the person you are now is only because of all of these people behind you, and what you do in the future very much depends on your understanding of that.”

In both an all-College email in September that discussed the CDC’s work and an interview with the Record, President Maud S. Mandel, who is not on the CDC, underscored the necessity of the College’s examination of its institutional history.

“It’s very important for the College to take stock of its history — I think that as a historian, as an educator, and as a president,” Mandel said. “It’s important because who you are in the present is an outgrowth of who you were in the past. I think you can only aspire to change if you first take full measure of where you’ve come from.”

While the CDC is conducting some historical research itself, it is concentrating more on how to synthesize and present the history that generations of College community members have already uncovered, said Associate Dean for Institutional Diversity, Equity and Inclusion and Professor of Latina/o Studies and Religion Jacqueline Hidalgo, who is also a co-chair of the committee. The CDC will publish its recommendations by the end of the academic year, according to Hidalgo.

One institutional response under discussion is the payment of reparations to groups that the College has harmed, Hidalgo said, though she stressed, “we’re a long way from making them happen.”

“We have discussed reparations not only for descendants of those enslaved by the Williams family but also for the descendants of local communities who suffered from anti-Black violence during Williams’ history,” she wrote in a follow-up email to the Record. She also mentioned the possibility of scholarships to support students from the Stockbridge-Munsee Community and the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, as well as Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) students.

“There’s also … other kinds of broader projects of reparations that might not look so strictly financial but would likely entail financial investment,” she said.

“I just hope people are comfortable with that term ‘reparations’ and it flows off the tongue easily,” said Assistant Vice President for Campus Engagement in the Office of Institutional Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Bilal Ansari, who is also a co-chair of the CDC. “Because sometimes it’s a hard thing to grapple with. That’s one of the things we hope to grapple with.”

Then there’s the issue of names. Ephraim Williams’ name and the moniker “Eph” are ubiquitous at the College. A few alums have reached out to Alumni Relations and the CDC’s subcommittee on alums asking the College to weigh the significance of its name, according to Hidalgo. “They pose it as a question… ‘Does knowing this history about Ephraim Williams impact our feeling about the name Williams as a college?’” Hidalgo said.

Understanding the College’s history, and evaluating the meaning of it, is important for students especially, Murphy said.

“It’s students who will be doing the work in the future to figure all of this out and to make decisions about how we venerate someone like Ephraim Williams, and Amos Lawrence, and other people whose names are attached to buildings, whose names are attached to endowments,” he said. “Ephraim Williams is the place to start, and then everything kind of radiates outward from there.”