Special Collections event dives into institutional history

February 19, 2020

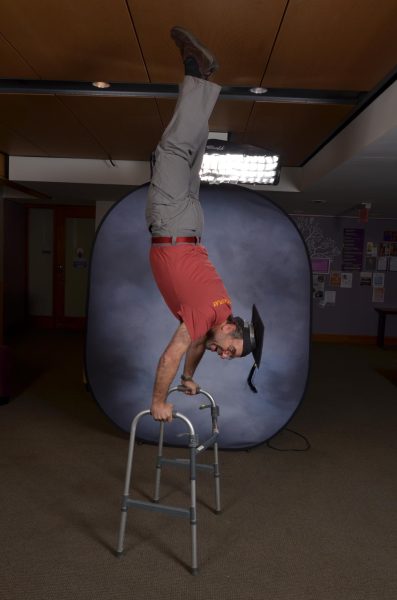

Community members transcribe documents from the College’s early history at the Transcribe-a-Thon last week.

“The name of [the] Indian boy who lives with me is Joshua Shantupe,” reads the first line of a 19th-century letter in the library’s Special Collections. “The time I want him bound is four years, … his business principally farming.”

This letter was made available to students during the Transcribe-a-Thon last Wednesday, an event dedicated to digitizing documents from the early history of the College and surrounding area, especially with regards to how the Williams family acquired its lands.

As a friend and I, with the help of history professors and library archivists, pieced together the contents of this letter, it slowly unfolded that a man, who paid for a Mohegan boy to be indentured at his farm, decided that he could not teach the boy how to read, which was one of the conditions of the indenture. He wrote this letter to the overseer of a band of Mohegans to complain.

“The boy has been at school some months since he lived with me … but when he has been put to spelling, there could hardly be any combination of letters that would not spell either Cider or Rum & generally speaking, I should consider it a less hopeless errand to undertake to learn a Dishley bull to top a haystack or a merino sheep to shake an appletree than to learn an Indian the alphabet.”

The elaborate insults and stereotypes in this letter may one day be analyzed by a historian trying to piece together the culture of the period, or perhaps the College’s own early history.

This letter “speaks to painful histories of how settler colonialism caused some Native children and young adults to be removed from their homes, kinship networks, and tribal communities and placed into colonial settings as indentured, enslaved, or otherwise unfree laborers,” Professor of History Christine DeLucia wrote in an email. “This repeatedly occurred across the Northeast beginning in the seventeenth century. Colonial authorities paternalistically sought to ‘assimilate’ or ‘acculturate’ Native people into Euro-colonial ways of being and undermine Native cultures, identities and sovereignties.”

The event took place during a larger movement as colleges and universities across the nation come to terms with their pasts. About 40 people, including faculty, staff and students, participated in the event, held in the Stetson Reading Room.

After coming up with the idea for the event, DeLucia and Professor of History Alexander Bevilacqua approached Anne Peale, a special collections librarian, and Lisa Conathan, who is the head of Special Collections. They said they drew inspiration from similar events at other institutions, such as the Folger Shakespeare Library.

At the Transcribe-a-Thon, DeLucia said one of the goals of the event was to answer questions relating to the people who originally lived on the land that the College now inhabits. Such topics included the original ownership of the land, what the land was called before it was named Williamstown and how it continues to be a native homeland today.

DeLucia said she hopes the event will help put Ephraim Williams, the College’s founder, in “a sharper context,” especially with regards to his “quite fraught relationship with the native community at Stockbridge” and “his role in the battle of Lake George, when he dies, and then his will winds up as the foundation of the college.”

The importance of the Transcribe-a-Thon also lies in the stories it might reveal.

“When you look at these deeds, none of them are straightforward. They all have a story to tell,” Conathan said. “There’s always some complicated, convoluted story in there.”

DeLucia said that history is about uncovering stories, and in order for an institution to move forward, it must understand where it came from. Stories of the College’s early history are crucial to making meaningful decisions in the present, she added.

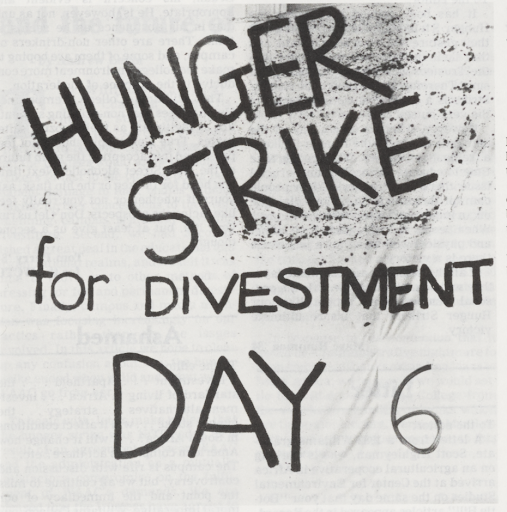

“Some of that has to do with quite difficult histories, histories of involvement with slavery [and] with land dispossession that are foundational, not only to Williams but to other institutions,” DeLucia said. “If those histories remain un-talked about … then the College is really not aware of its own identity.”

Along with these more difficult histories, there are also histories to discover that can shed light on people and communities that have always been a part of the College but may not be recognized as such.

“There’s equally an interest in spotlighting those histories as well, so that the story is not narrowly told,” DeLucia said.

A goal of the event also involves the Stockbridge-Munsee Community Band of Mohican Indians, whose tribal homelands the College occupies.

“One of the big areas of interest in these collaborations … is how Williams could make historical resources that are here, that are either by or about the tribe, more accessible to them as they’re doing very meaningful work about their own heritage, and finding ways to activate that digitally and otherwise,” DeLucia said.

Two history majors who attended the event, Annie Kang ’20 and Molly Egger ’20, transcribed a letter in which a Mohegan man, Joseph Johnson, requested money from the Connecticut treasury to finance his tribe’s exodus out of the state.

The letter “attests to the proactive, resilient efforts by Native people such as the Mohegan tribal member Joseph Johnson to strategically devise pathways forward that would enable community continuities and self-governance,” DeLucia wrote in an email to the Record.

The Transcribe-a-Thon is just one part of a wider effort at the College to confront its early history.

“The way we recount our history says a lot about who ‘we’ are,” President Maud S. Mandel wrote in an email to the Record. “As the college has become more diverse, people have questioned that ‘we:’ who’s included, or not? Who’s celebrated, or not? Whose perspectives are reflected, or not? At times, college leaders faced these questions proactively. In other cases, students, faculty, staff and alumni asked for or demanded it.”

Mandel noted that exploring the College’s history is an important component of the Strategic Planning initiative on diversity, equity and inclusion. “Revisiting our institutional history gives us a chance to incorporate diverse perspectives in our shared story: to expand the ‘we,’” she wrote.

“Thinking aloud, down the road, I would be thrilled if [institutional history] were built into, say, orientation a little more substantially,” DeLucia said, “so people have a sense of the long-term history of this place, which goes back thousands of years, not just 1793.”